Why history will be kind to Joe Biden

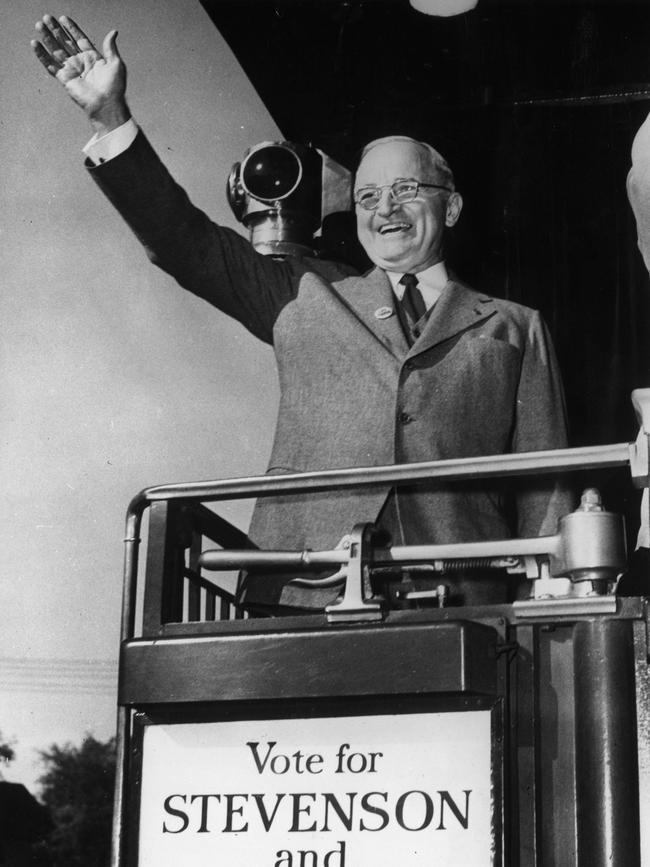

When he left office in 1953 after the election of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, Truman’s standing in the opinion polls was in the low 30s. Now he is regarded among the near-great presidents.

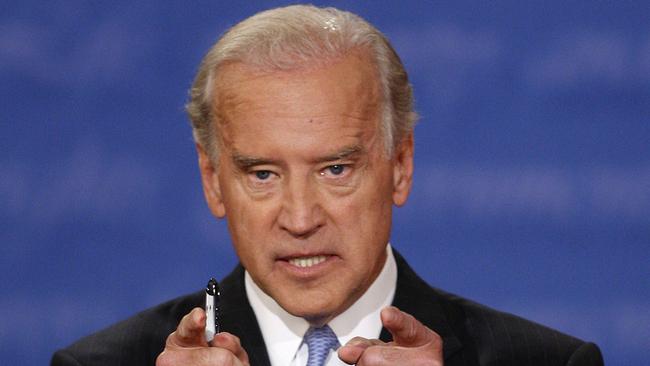

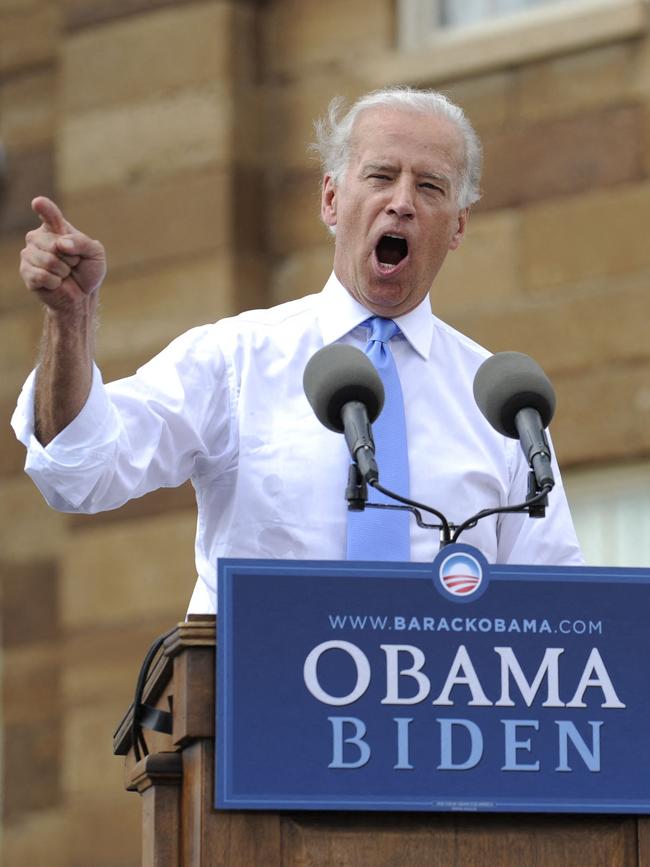

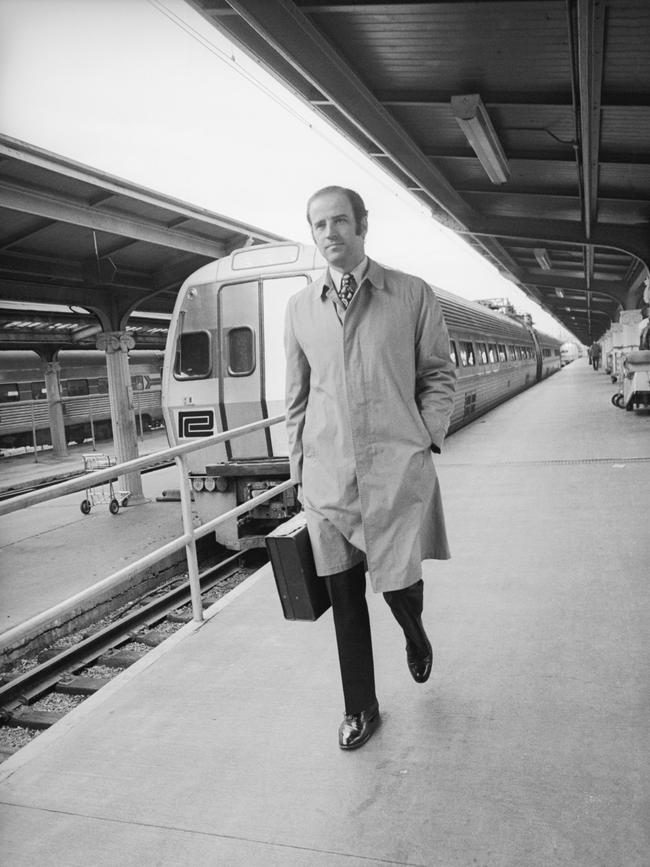

A man of humble origins, like Truman, Biden was a product of Scranton, Pennsylvania, which gave him an outlook on life that did not vary throughout his half-century of public service: entering as one of the youngest US senators, serving as Barack Obama’s vice-president and ultimately stepping down as the oldest US president. Biden is a common man who understood where he came from and respected the ordinary folk who sent him on his way.

By contrast, a poll of 154 academic experts in the Presidential Greatness Project ranked Donald J. Trump as the worst president in the history of the republic.

Presidential legacies matter, not only to individual presidents but also to the self-respect and health of the republic itself.

Ronald Reagan understood this perfectly, which is why he embraced Truman’s legacy. Obama appreciated the significance of the presidential legacy, which is why Theodore Roosevelt resonated throughout Obama’s time in the Oval Office.

The Biden legacy will require the passage of many years to become authoritative, but a few early observations may be made.

Biden’s legacy fits neatly into three overlapping areas of presidential engagement and of power.

First, following inauguration in January 2021, the new President set about stabilising the office of the presidency itself. It is a matter of fact that Trump’s cabinet had become a series of temporary appointments with the crude slogan “you’re fired” routinely echoing through the corridors of the White House. Sometimes, as with FBI director James Comey, the sacked appointee learned of their fate through the media.

The Biden cabinet has been remarkably stable, with serious political players such as Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Attorney-General Merrick Garland, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin remaining at their post to contribute continuity and constructive policymaking in their portfolios.

Second, foreign policy has been far more predictable for allies and adversaries. The turning point for the Biden administration came with Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Biden acted with the resolve of Truman when informed of the communist invasion of South Korea in June 1950.

Travelling back to Washington from Independence, Missouri, Truman decided to mobilise not only the US military but also the UN in support of the defence of the South from aggression.

Biden realised that US support for Kyiv, while vital, was insufficient without broad global diplomatic and material support. To this end, Biden’s leadership revitalised NATO in full and guaranteed a growing system of aid that the courageous Ukrainians turned into successful defence.

If returned to the White House, it remains to be seen how Trump would end the Ukraine war “in 24 hours”, as he has boasted.

What we can say with certainty is that without Biden’s efforts an expanded NATO, now including Sweden and Finland, would not have assumed the muscular role that several of its members have adopted.

Former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright was right. America remains the “indispensable country” and Biden will be viewed by history in the same light as Truman in the successful defence of South Korea.

From an Australian perspective, the Biden commitment to the AUKUS trilateral security pact with Australia and Britain is of critical significance for our security and the security of the Indo-Pacific.

Nuclear-powered submarines are one critical change-agent in the strategic balance. Pillar two of AUKUS, which envelops the most advanced technologies on the planet, including quantum computing, will reset the balance.

AUKUS has prospered under Biden’s watch, which is why other Five Eyes countries and Japan are eager also to join.

True, there have been failures, including the appalling withdrawal from Kabul and the incoherence of Washington’s policy on its own border with Mexico. But when it really counted Biden stood up, particularly for Israel in its hour of danger, and delivered the might of the US to the assistance of American allies.

Third, on the domestic front, Biden delivered congressional majorities where the sceptics had argued none was possible.

The Inflation Reduction Act broke new ground on environmental protection and climate change response. Together with the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, such laws stand as monuments to an administration that sought to work with congress, despite the frustrations inherent in dealing with ideologically motivated minorities.

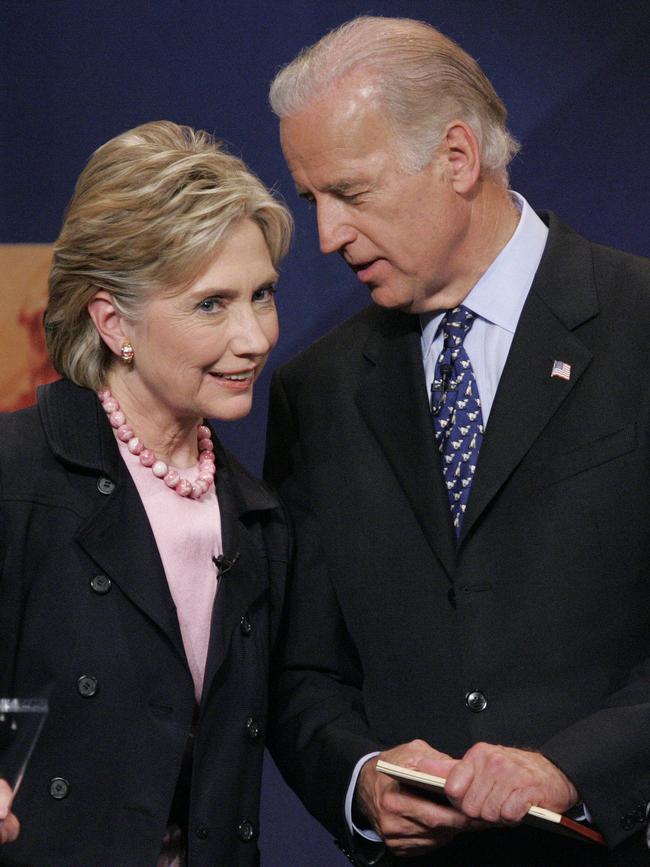

Biden’s legacy will be framed, in part, by the outcome of the November election. He tarried too long in announcing his exit, but he was always aggrieved by being bumped out of the race in 2016 for Hillary Clinton. If he had acted earlier, as did Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, and given the Democratic Party more time to choose a successor, then the US political landscape would likely look more promising for the Democrats today.

But in the tradition of voluntary departure established by George Washington, Biden lived the words spoken by Eisenhower to the newly installed but shaken president Johnson on the night of John F. Kennedy’s murder: “The country is far more important than any of us.”

Stephen Loosley is a former chairman of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

More Coverage

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr, the 46th President, will be bracketed with Truman as a president who exceeded expectations and delivered on domestic and foreign policy agendas.

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr, the 46th President, will be bracketed with Truman as a president who exceeded expectations and delivered on domestic and foreign policy agendas.

The definitive remark on the legacy for a US president was reported to have been an observation by 33rd president Harry S. Truman: “Do your best, history will do the rest.” US history has been justifiably kind to Truman’s reputation.