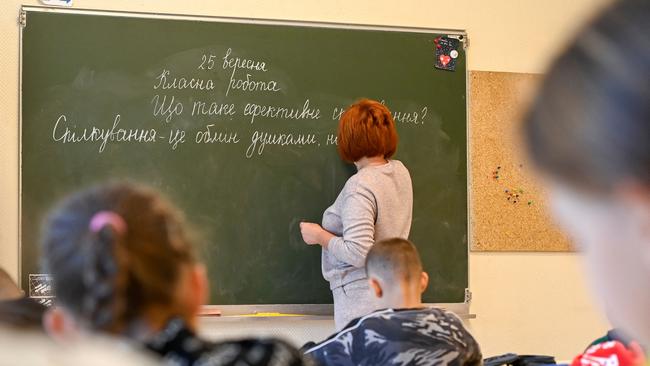

“I’ve been teaching for 22 years. Over that time student behaviours gradually worsened but this has dramatically accelerated since Covid,” lamented one teacher in online forum r/AustralianTeachers.

These anecdotes are backed up by large-scale survey evidence. In 2022, a Monash University study of 5000 teachers found that one-quarter did not feel safe in their job. In online forums, teachers share their war stories. “I’m on duty in a break and I go to tell a group of kids sitting out of bounds and out of sight to come back, and they just say ‘nah, we’re not gonna do that’,” writes one teacher.

“I signed up to teach not to manage behaviour. I always knew I would have to deal with some behaviour, but not to the point where my class has to be evacuated for safety,” reports another.

Forget about microaggressions, or poor-taste jokes (reasons for other workplaces to be described as “toxic”) for teachers, a toxic workplace consists of chairs being thrown around rooms, and weapons being brought to class.

“I’ve had to confiscate knives from students and I’ve been punched in the stomach while pregnant by a student,” reported one teacher in a 2019 study. And it isn’t just the experiences of those teachers who post online. A 2021 survey of 570 Australian teachers found that: “Behaviour management was … frequently nominated by teachers as the greatest challenge they face. Teachers explained that just a small minority of disruptive students can have a large and negative impact on the majority, and that managing these behaviours takes even further time away from teaching. Sixty-eight per cent of teachers indicated they spend more than 10 per cent of their day managing individual student behavioural issues. Seventeen per cent said that this consumes over half their day.”

Parents are not much help, either. Teachers report the parents of defiant pupils often have uncooperative attitudes themselves, and can be dismissive of their child’s bad behaviour. One teacher online shares their daily routine of emailing parents about their child’s disorderly conduct, only to receive such responses as “hahaha sounds like them”.

Within three years, NSW is projected to have a shortfall of 1700 secondary teachers, according to federal Department of Education modelling. And this shortage will be most acute in science and mathematics. This is part of a broader trend across Australia, where more than 9000 secondary teachers are expected to be in short supply, and more than 50,000 teachers are anticipated to leave the profession between 2020 and 2025, including 5000 aged 25 to 29.

Currently, one in five pupils in regional NSW is taught maths by a non-specialist teacher, and up to 70,000 pupils could be affected by teacher shortages by 2030. Despite a government strategy to add 3700 teachers over the next decade, there is still no plan to address teachers’ work conditions, such as deteriorating classrooms and stress, in order to make the profession more sustainable.

So what is to be done? Greg Ashman, a deputy principal and education researcher, argued in a NSW Senate inquiry earlier this year that the first step to fixing a problem is recognising there is one.

The Senate inquiry’s terms of reference emphasised that, based on a 2018 Program for International Assessment analysis, Australian classrooms are some of the most chaotic globally, ranking 69th out of 76 jurisdictions.

Ashman argues that part of the issue is that our education bureaucracy is influenced by ideologies that do not recognise bad behaviour for what it is. Poor behaviour is interpreted as a “form of communication,” meaning a child or teenager is in need of extra support, not consequences.

This is reflected in the comments posted by teachers in online forums: “Apparently we are not supposed to use the term ‘behaviour’ anymore,” wrote one teacher just this week. “Apparently behavioural issues are ‘wellbeing’ issues. And behaviour is a stigmatising term for young people.”

In some cases, bad behaviour is medicalised as Oppositional Defiant Disorder – a disorder that is recognised by the The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5). It may be appropriate to use this label in some cases. However, once a disorder has been diagnosed, all consequences can be interpreted as “discrimination”. Schools are required to be “inclusive” and that means being inclusive of children with ODD.

Disability and mental health diagnoses of all types are on the rise. Last year, 22.5 per cent of schoolchildren in NSW were identified as having at least one “disability”, a label that often works as a get-out-of-consequences-free card.

Given the war stories and dire statistics, perhaps it should be no surprise that 40 per cent of teachers leave the profession within just five years. We do not expect other professionals to work in environments where they are disrespected and, at times, abused just for doing their jobs.

But ultimately, the real victims in all of this are the pupils who are just trying to learn. Disruptive children make it hard for everyone to concentrate, and one problem child can detrimentally impact an entire classroom.

Given the lack of control in our classroom environments, perhaps it is no surprise our literacy and numeracy standards continue to decline. Despite the hundreds of billions spent on education.

Claire Lehmann is founding editor of online magazine Quillette.

Australia is facing a dire teaching shortage, and one of its root causes remains under-addressed: out-of-control classroom behaviour. Privately, and in online discussion groups, teachers report feeling burnt out and unsupported. They face defiant pupils, uncooperative parents and administrators with impossible expectations.