However, Taiwan has become – if at first diffidently – a testing ground for democratic resilience. So has Australia, in part through our own relationship with – or, at the political level, our distancing from – Taiwan.

Peter Dean wrote on these pages a week ago that “a new public debate on Taiwanese and regional security must emerge”. He is quite right.

It’s now 75 years since Taiwan was invaded by mainland Chinese, led by Chiang Kai-shek and his defeated Nationalist army. It was a follow-up invasion, coming after the arrival of Nationalist forces in 1945 following the Japanese defeat. Earlier, the Taiwanese had been handed to the Japanese, in 1895, by the Qing government in Beijing. And before that, many in the indigenous population (the ancestors of most Pacific Island peoples) opposed the first effective colonisers, the Dutch who arrived in 1624.

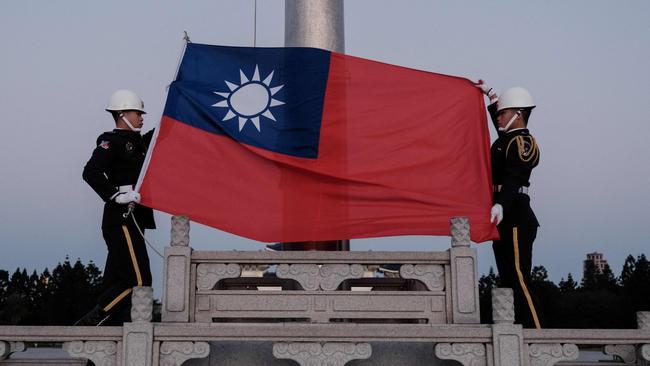

For much of the past 75 years, although not entirely consistently, Chinese Communist Party leaders have threatened to join this list of invaders. But over the past 30 years the Taiwanese have developed a resilient democracy to match their inventive economy. In 1949 Taiwan was poorer than most of China. Today its people are on average almost three times more wealthy than the average Chinese.

Taiwanese people argued, campaigned and fought to run their own affairs long before the People’s Republic of China was formed. In this context, today’s self-governing status quo is a natural development.

Very few people who live in Taiwan identify themselves as “Chinese”, despite speaking languages often categorised as Chinese. In the latest Pew poll conducted in 2024, 67 per cent described themselves as Taiwanese, 28 per cent as both Taiwanese and Chinese, and just 3 per cent as solely Chinese.

The PRC – especially since the dark days of Covid, and since it started its continuing economic slide, along with its shift towards greater protectionism – does not hold the allure it once did for Taiwanese people, including those running businesses who played such a crucial role in China’s rapid modernisation and industrialisation, some of whom have reinvested from China back to Taiwan.

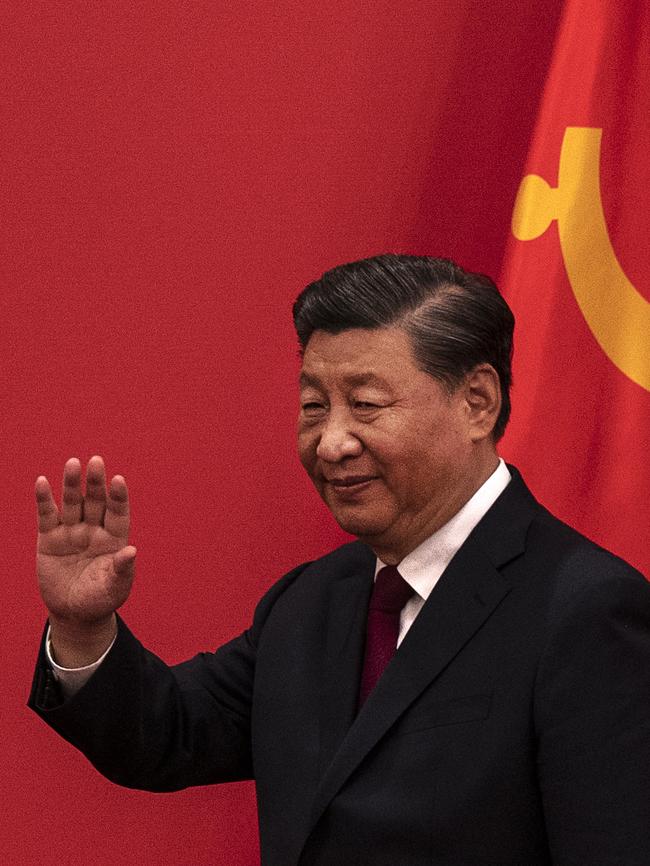

However, the allure of Taiwan’s “real estate” to use the now globally infamous term introduced recently by Paul Keating, has intensified this century for General Secretary Xi Jinping and the party elite, seeking tangible glory to enable the pronouncement of the PRC’s rejuvenation.

Xi might even be satisfied with a form of “vacant possession” of the territory of Taiwan, in a way commensurate with his newly direct form of rule in Hong Kong, whose democratic political elite are mostly either in jail or in exile.

The people of Taiwan haven’t sought the responsibility of being an international testing ground – their elections in January underlined their understandable domestic priorities – but it has become inescapable.

What is being tested, what is at play, as the story of Taiwan spools out? The outcomes are too weighty for us in Australia – and those in other free countries in our region, or indeed the wider world – to let burden the shoulders of the 24 million people of Taiwan alone.

The tests implicit in the way Taiwan’s fate is shaped from here on, include: Is the Chinese-speaking world a place of natural, innate diversity, or is it a single ethnic identity? How should this world live respectfully alongside ancient indigenous cultures such as those in Taiwan? Must the rest of the world agree with the CCP’s largely politically directed version of the history of China and of neighbouring regions and peoples?

Would Australia tolerate its resources such as iron ore continuing to be shipped to China in the event of a Taiwan blockade or kinetic conflict? How does the world define sovereignty? By a capacity to control everything within borders and to police those borders, by a UN pronouncement, or by that of a neighbour?

Last month the Australian Senate passed a highly significant motion effectively affirming Taiwan’s right to participate in international bodies such as the WHO, from which it has been excluded. As the incoming chair of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, Australia should invite Taiwan, a trading exemplar, to start negotiating to join.

Other Taiwan tests include asking how important is self-determination, and where and when should it be permitted?

How do Taiwan’s neighbours, including Australia, shape their own international relations and policies – can interests be separated fully from values? Do democracies have an interest in supporting jurisdictions with which they share values? Are interests, including economic interests, sometimes placed at peril by the values of economic partners, including those that are authoritarian?

If Beijing takes Taiwan, what would be its logical next step? But if the PRC fails in an armed attempt to do so, might this comprise an existential challenge for its ruling party?

Such epochal tests illustrate that this is very far from being a matter purely of a brutal landlord seizing control of his own “real estate”, and probably evicting – or eviscerating – the tenants’ leaders.

Taiwan’s President Lai Ching-te said at his inauguration four months ago: “Democracy, peace and prosperity form Taiwan’s national road map. They are also our links to the world.” Including of course to us in Australia, whose own testing ground includes how we respond.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute, and vice-chair of the Australia Taiwan Business Council.

Visitors to the delightful island of Taiwan – where Australian tourism is growing steadily – are discovering to their surprise that neighbouring China does not weigh heavily on most people’s minds these days.