Having been on Twitter since 2013, I’ve had my fair share of trolling. When members of the far left hurl abuse, they call me a “Nazi”; when the far right does it, it’s “Grandma” for being the other side of 30. The worst abuse cannot be put into print, of course, and it comes mostly from anonymous troll accounts.

Such experiences can be distressing. So one may be surprised to learn that, despite copping my fair share of abuse, I am a supporter of pseudonymity on the web and in publishing. Pseudonyms protect individual privacy. And because privacy is an essential feature of a free society I believe it is important to recognise its legitimate use.

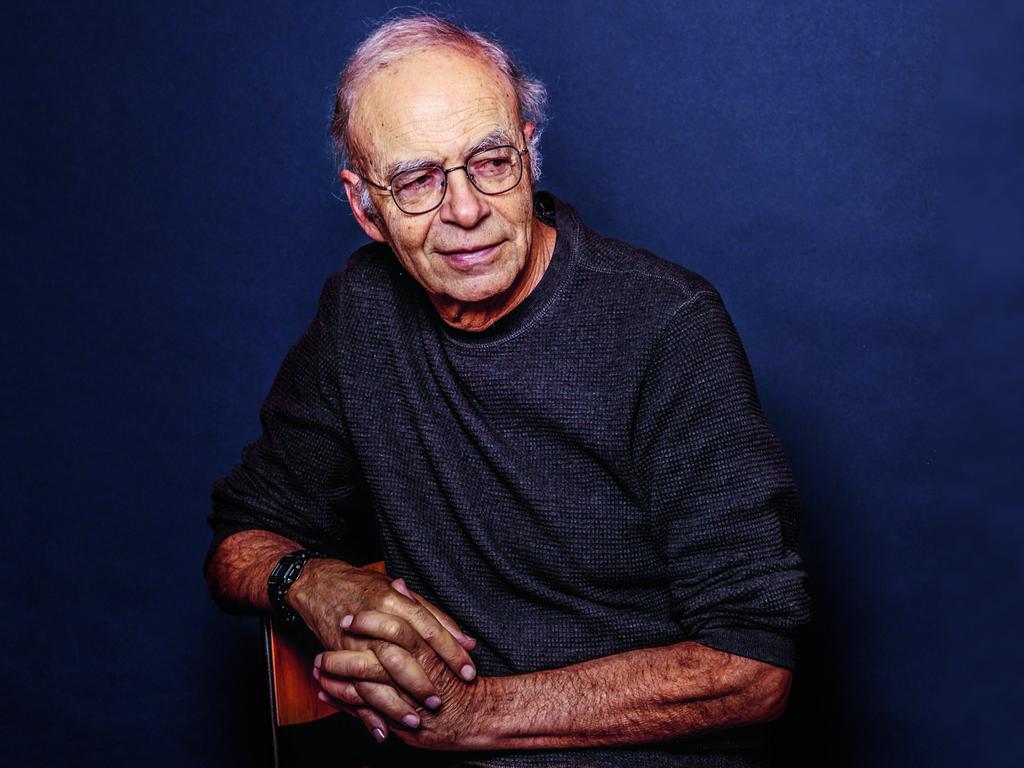

On Wednesday this newspaper revealed that this month Princeton professor of philosophy Peter Singer will launch a Journal of Controversial Ideas that will allow researchers to publish articles under noms de plume. While some believe we should always be willing to out ourselves in public debate, others among us believe the ability to explore contentious ideas without an aggressive personal backlash can be a positive.

No society can be considered free when an individual’s private world is open to interrogation and unfortunately — thanks to the internet — the world we live in is one where our private worlds are interrogated every day. Not by the government but by corporations that track where we go, what we do, what we buy and who we talk to via the computers that sit inside our pockets and on our bedside tables while we sleep.

Social media companies know who we associate with, what products we like, what our cultural tastes are and what values we hold dear. They even know what makes us happy (often cat videos) and what makes us sad (often police brutality). Search engines know what makes us insecure (bad skin) and what turns us on in personal moments of solitude (you get the picture).

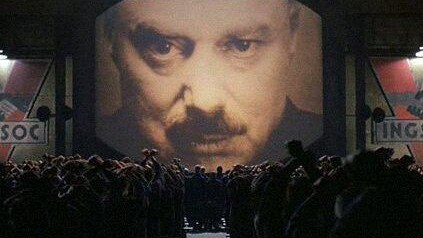

In many ways, these companies know us better than we know ourselves. Unlike mortal beings who are adept at self-deception, the data collected about us does not lie. In the face of Digital Big Brother, pseudonymity is just a way of encrypting our identity when it is being commoditised by those who do not have our best interests at heart.

While it is indeed true that anonymity on social media has led to a coarsening of discourse and a degradation of interaction online, there are often good reasons for people to conceal their identities that have nothing to do with abuse or trolling. And it’s worth remembering that a pseudonym, or an alias, is not quite the same as being anonymous online.

A pseudonym is a fictitious name that one uses that is connected to a real, legal identity. Historically, writers have used pseudonyms or pen names to publish in magazines or newspapers opinions that may have been politically controversial for their time, or simply used by professionals to preserve the confidentiality of their clients or patients. Early female novelists used male pen names because they (correctly) thought they wouldn’t be read widely without them.

A pseudonym ensures that an individual’s privacy is protected, but also ensures that an opinion being offered up comes from a real person and not an automated machine programmed at a Russian or Chinese troll farm. We have published writers under pseudonyms at the online magazine I founded, Quillette, but only after verifying the author’s real identity. We do this because some of our writers work in professional industries that are highly conformist, such as academe, where having unorthodox opinions can risk one’s career.

I believe that allowing for pseudonymous writing is especially vital when a society takes an oppressive cultural turn. There should be no doubt that Western societies have taken such a turn in recent years. The vast loss of privacy we have experienced in the past two decades has occurred concurrently with the rise of an illiberal and moralistic culture that is slowly suffocating our social worlds.

Pre-modern forms of behavioural control are back in fashion, with the threat of snitching and mobbing or stalking anybody who dares express a independent thought. From the sciences to the arts, independent thinkers are being punished for heresies that were invented as recently as yesterday. Academics are being tarred for publishing empirical data, evolutionary biologists are being disciplined for thought experiments and writers are being denounced for exploring the creative imagination.

To understand just how much privacy we have lost, it’s worth taking a brief step back in time to realise where we are today. In the early days of the internet, it was thought this new technology would open up the world and make us more tolerant through being more connected to one another. Increased interconnectivity would lead to more pluralism and democracy (or so it was thought), and social media was celebrated just 10 years ago for bringing about revolutions such as the Arab Spring. Yet this early utopian vision of the net has not materialised. From Peru to Poland, our societies are becoming polarised and the future looks more balkanised than it does open and tolerant.

Online pseudonymity is simply a way of reclaiming the privacy and personal sovereignty that we have lost in this brave new digital world. Although I am pessimistic about the trajectory of Western societies, I am optimistic about the ability of humanity to navigate and overcome such complex and seemingly insurmountable problems. New technological tools that enable encryption, and older tools such as the time-tested method of the pseudonym, will enable us to pass liberty on to future generations.