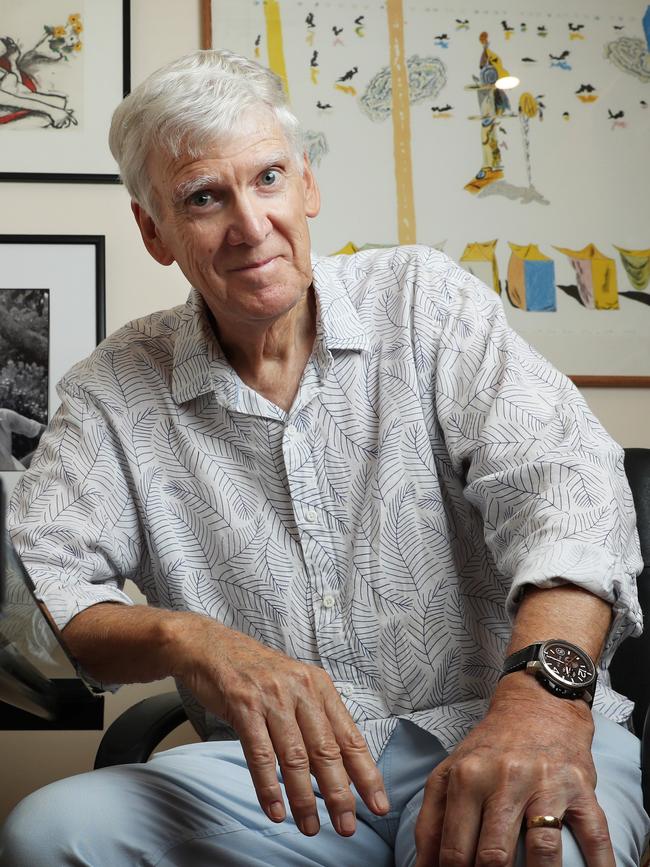

In 1971 I wrote a play called Don’s Party about the night of the 1969 election, based, perhaps a little too closely, on the events of the actual party I threw that night in suburban Melbourne. With an election looming I started to think about the likely differences in election night parties then and now.

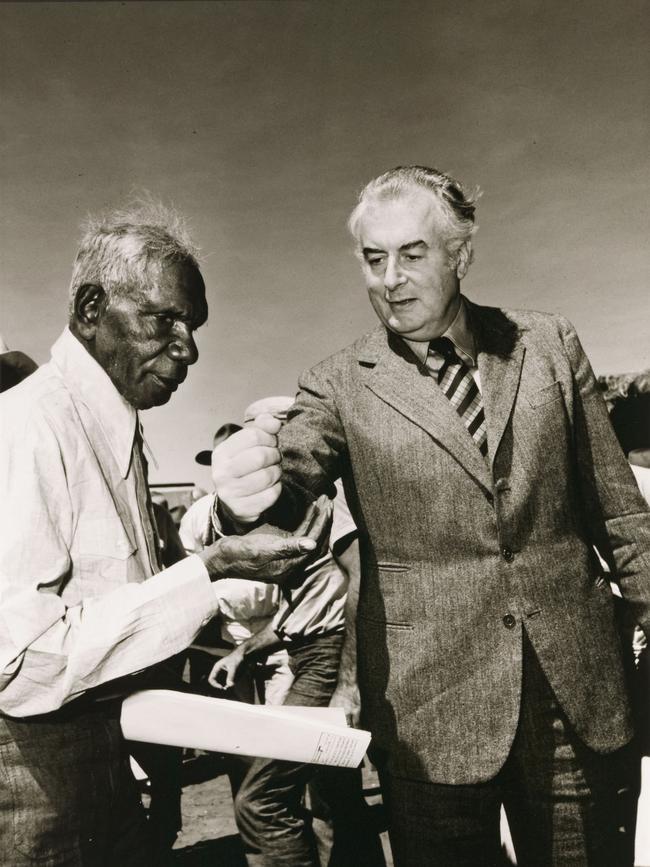

In 1969 Gough Whitlam was expected to win and early in the night it looked as though he would but the euphoria of the mainly Labor supporters at the party faded as it became apparent the victor would be John Gorton’s Liberal Party. A change of government then would, as it did three years later, have brought big changes. There were big stakes, and big stakes generate strong emotions.

In 1969 an election loss was a total punch in the gut but at this election a Labor Party approving new coalmines hand over fist and offering as its main policy a small cut in income tax is harder to get excited about than one promising the end of conscription, the end of the White Australia policy, Medibank, no-fault divorce, free university education, environmental protections, a greatly increased arts budget and an independent foreign policy.

Back then the guests at Don’s Party were still in their late 20s and, with feminism still in its infancy, men still assumed women were just as eager for sexual adventures as they were. And women were more hesitant to assert themselves until their emotions finally boiled over. The ferocious tongue-lashing Kath delivers to Don at the end of that shambolic night is still often used as an audition piece for entry into acting schools by women enjoying unleashing full fury on the male species. On this election night the men wouldn’t dare behave towards the women as they did at Don’t Party. What was then considered an innocuous pat on a woman’s bottom could now mean the end of a promising corporate career.

In 1969 all of the guests at Don’s Party were in their own homes by their late 20s as the cost of a home was roughly 2½ times their annual wage. Today that cost is more like eight or nine times, so although the real income of a family has more than doubled over that time, mortgage repayments then were minuscule compared to today, so cost-of-living issues didn’t top the agenda back then as they will this election night.

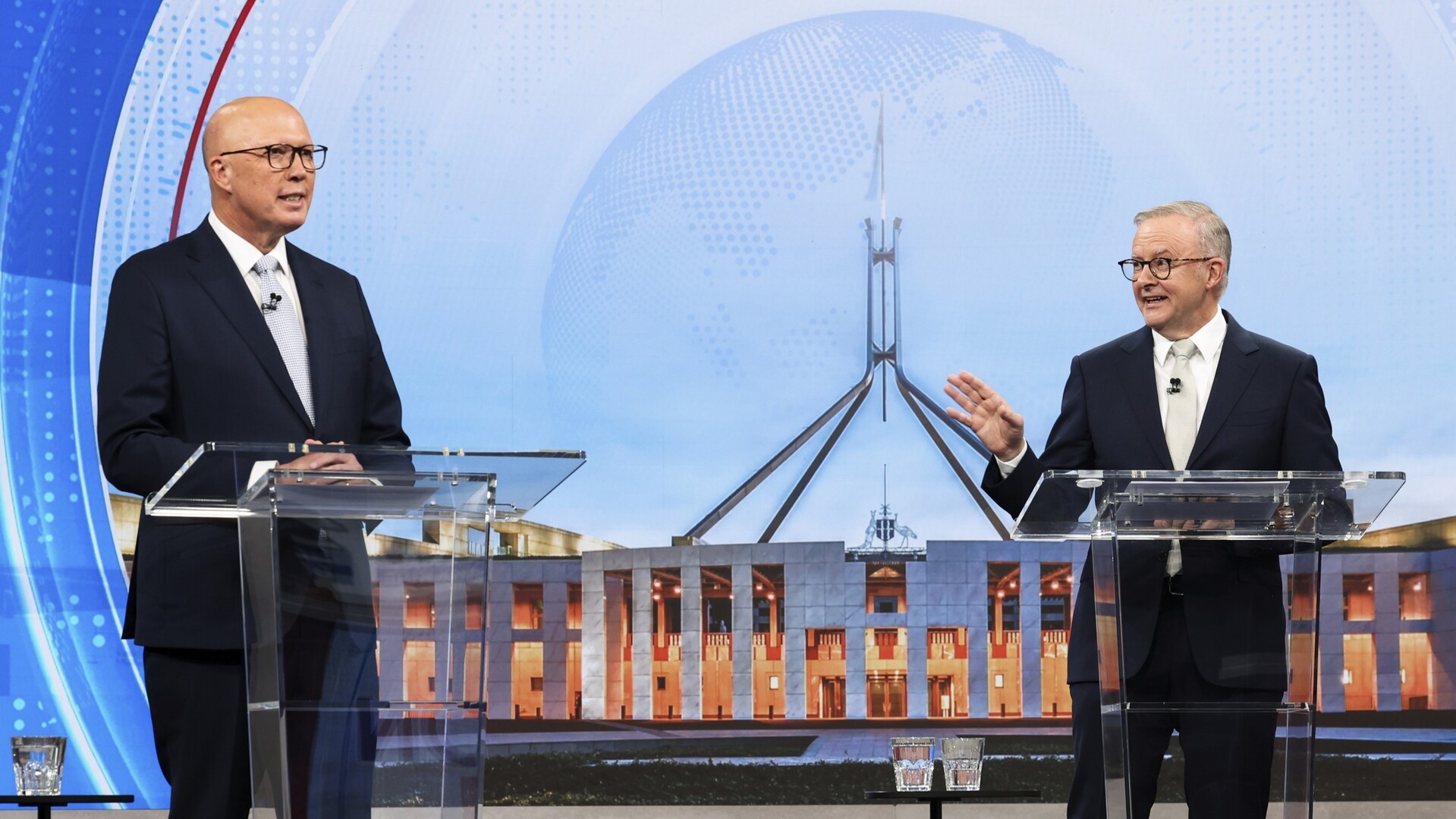

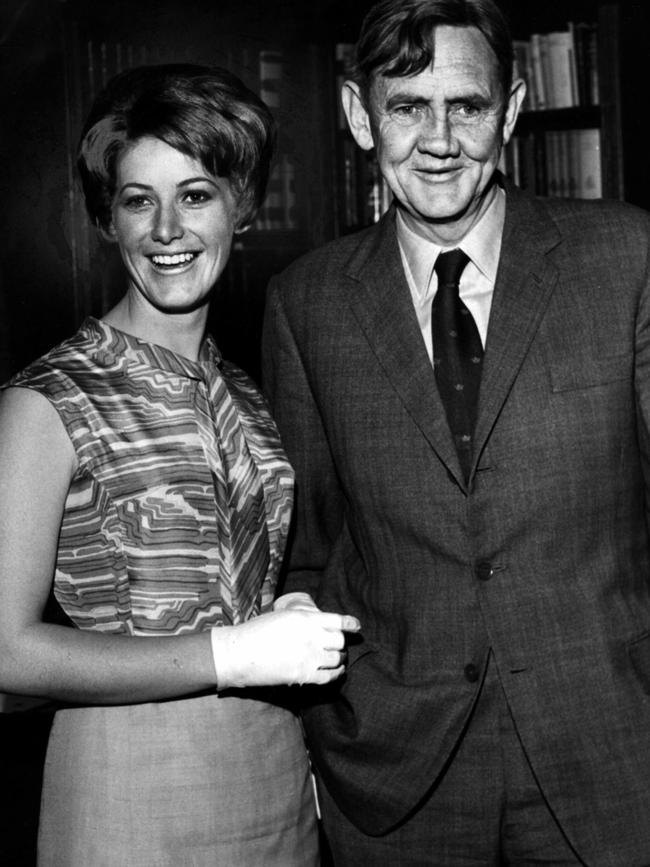

In 1969 the two leaders were arresting personalities. The magisterial emperor in waiting, the mighty Gough, opposed by the ultimate boyo, John Gorton, who had Sydney awash with rumours after his backstage visit to Liza Minnelli at Chequers nightclub. Publicist Harry Miller, who was there, declared: “Let’s not beat around the bush, they did it.” The account was strenuously denied by Minnelli. The incident might have dinted Gorton’s Christian following but his popularity soared. This election we have two leaders whose personalities are quite a bit less likely to inspire strong passions on election night.

Another obvious difference in election parties then and now was alcohol. Not that the amount of alcohol will diminish all that much on Saturday, but at Don’s Party endless longneck bottles of beer were consumed. Not a Penfolds 389 in sight, even though you could buy them back then for a couple of dollars.

Even a Henscke Hill of Grace was just over five bucks but not even the Liberal-voting renegades at the party, Simon and Jody, arrived with one. Simon did tentatively suggest Jody might like a gin-and-tonic but Don had forgotten, or more likely never thought it necessary to have any on hand.

Back then class and voting patterns were much more clearly defined. Don’s Party in fact was anomalous for its era as Don and his friends were part of that first wave of university graduates who voted Labor.

In general, if you were working class of moderate means you voted Labor, and if you were managerial and well off you voted Liberal. And there was logic to it. If you weren’t wealthy you knew the Labor Party believed in spending tax money for the common good, and the Liberals hated their tax money being spent on anything other than themselves.

As the postal votes continued to flow towards Gorton later in the night, Mack sourly remarks that postal votes always favour the Liberals as they’ve got more money to travel.

The thought that a party dedicated to women’s rights and the environment would win blue-ribbon Liberal seats in 2025 would have seemed incredible in 1969, as would the thought that working-class voters would increasingly support the Liberal Party, not for economic reasons but because the Liberals’ conservative social values aligned with theirs.

Kristin and I did think about having an election night party; we live in Noosa, which is a perfectly good place to live, but as we lined up to vote early, everyone else in this ageing affluent electorate had the blue Liberal how-to-vote card in their hands. The beleaguered Labor Party volunteer looked hugely relieved when we asked for one of hers. Sorry, Albo, but the swing to Labor isn’t happening up here.

In truth, when we cast about thinking who we could invite we remembered that the only other couple we knew who voted the way we do were away on holidays.

So we’ll be sitting here alone, sharing a bottle of Australian-grown Sangiovese, thinking of the wild parties of our distant past, and although political passions will be less intense we’ll still care.

We still believe the Labor Party is more likely to care about the common good than the other lot.

But not nearly as much as the heady days of 1969, when an election result could change the direction of a country and when an election party could cause full-on shouting matches and break up marriages. And provide me with precious material to write about.

David Williamson is a playwright and screen writer. He is the author of dramas including The Removalists, The Club, Don’s Party, Emerald City and Travelling North.