Gough Whitlam’s multiculturalism experiment has failed Australia

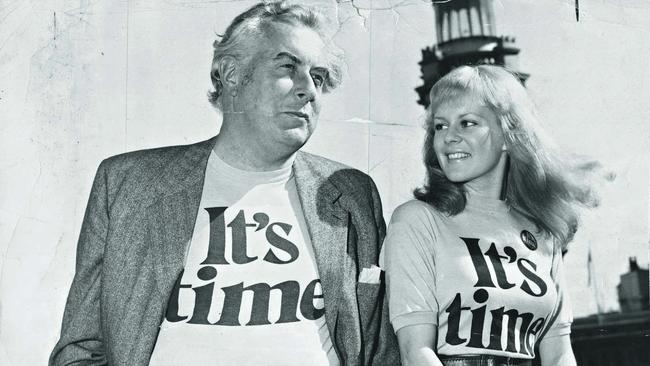

The anti-Semitic violence that has marred Australian life since Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023 highlights the collapse of the multicultural project the Whitlam government launched five decades ago.

The anti-Semitic violence that has marred Australian life since Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023 highlights the collapse of the multicultural project the Whitlam government launched five decades ago. That project aimed at promoting diversity without undermining social cohesion.

Now, as social cohesion buckles under an outpouring of toxicity and intimidation, it is increasingly hard to argue that its benefits outweigh its costs.

The complex of policies referred to as multiculturalism did not come in the wake of failure.

On the contrary, the approach it replaced, which stressed integration and assimilation, oversaw Australia’s spectacular post-war success in absorbing wave after wave of new arrivals.

During that period, which stretched from 1947 to 1972, the key political imperatives of defence and economic growth drove one of the proportionately highest levels of annual migrant intake anywhere in the world.

Labor immigration minister Arthur Calwell coined the slogan “populate or perish” in the 1940s when warning Australians they had, at best, 20 years to prepare for the next global conflict. With World War III likely by 1970, the nation needed a substantially increased population along with a large industrial base capable of supporting prolonged mobilisation.

Flooding into Australia, the new arrivals those priorities called for were immediately absorbed into the Menzies era’s boomtime economy. After a few years of hard work they could take advantage of the plentiful low-cost housing being built on the outskirts of major cities.

Soon enough, the recent arrivals and their families began leaving their original inner-city enclaves, providing new European leavening to the British-Australian dough of the great Australian suburbs.

Not only were they working, drinking and socialising alongside ordinary Australians, their children, as they grew into adulthood, began intermarrying. In their actions, the migrants, and the “Anglomorph” host society they had joined, ensured Calwell’s term “New Australians” was no empty signifier. Moreover, rather than moving to one locale only, they percolated everywhere.

Even as they continued to nurture the close ties any new migrant community requires, energetically forming their own ethnic clubs and associations, they also took advantage in their day-to-day life of one of the most distinctive features of Australian society – its remarkably open, egalitarian character.

Here status distinctions were fluid, class distinctions minimal to non-existent, and the social code of interaction placed a premium on low-key, easygoing acceptance.

It was, for sure, no utopia. The migrant’s journey is ineluctably difficult, even more so in a country that was resolutely monolingual. Yes, Australians were generally accepting, but there was often a lack of warmth. Tolerance could be counted on, but not a great deal more. It took considerable strength of will and adaptiveness, along with a modicum of good fortune, to realise one’s dreams.

But the strikingly high degree of success – measured by basic socio-economic indicators of home ownership, employment progress and long-term integration into the host nation – the migrants enjoyed clearly says something about the country in which they had arrived and forged their future.

This was an extraordinary achievement for a nation whose sense of identity was so bound up with its Britishness. The Irish trauma had certainly left its scars, but there was widespread pride in the institutions and practices Australia inherited from Britain.

David Malouf put it best, writing about his father, who was born in Brisbane to Melkite (Greek Catholic) parents from Lebanon. “He was passionately Australian,” writes Malouf, “but his patriotism included strong feelings for England, a place he had no connexion with and had never seen. He would have said, I think, that England represented all the things in the world he had grown up in that he most admired and lived by: fair play, decency, manliness, concern for the weak and helpless, a belief that life, in the end, was serious.”

Malouf’s father was scarcely unusual. Neither were his attitudes imposed on him by any constraining government policies, aimed at cramming “Australianness” down the throats of reluctant arrivals.

Rather, they were the outcome of a policy framework whose salient characteristic was, as academic, author and political thinker Frank Knopfelmacher observed, its stance of “benign neglect”.

Far from vigorously enforcing conformism, as later revisionists claimed, it did what an open society does best. Consistent with liberal principles, which hold people free to form their own associations, their own groups, their own culture and way of life, the policy left new arrivals largely to their own devices, leaving it to the slow gravity of acculturation to work its magic.

The attitudes of the old Australians helped that magic work. As long as the new arrivals didn’t import any “old world” grievances or political hostilities into their new home, Australians were more than willing to accommodate them within the wider circle of what historian and social commentator John Hirst called a “democracy of manners”.

Central to that “democracy of manners” was the unwritten rule that topics likely to produce heated division (most obviously politics and religion) should be studiously avoided, leaving the common fare of daily life as the central topic of neighbourly conversation. That was not, as later critics also claimed, because cultural, political or religious differences were dismissed as unimportant or as a secondary feature of individuals’ sense of self.

The precise opposite is true: it was because they could be so important as to prove explosive, shattering a society acutely conscious of the fragility that accompanied constant change.

It was this way of dealing with difference that, Hirst argued, provided “the social foundation of the peacefulness of Australian democracy”. One of the deepest and most ingrained habits of Australian life, it took shape, he shows, in the decades after European settlement in 1788.

The settlers arriving in those early years found they not only had to navigate an alien, often inhospitable, environment. They also had to confront, just as immediately, the alarming fact that ethnic and religious groups that for centuries had known little of each other but war and mutual loathing – Irish, Scots, English – now had no choice but to form a new society where no one ethnic group enjoyed overwhelming dominance.

This continued throughout the 19th century as convict transportation, gold rush migration booms and assisted migration schemes continued to feed new streams from these divergent groups into the one place.

Here the template that was so successfully followed in the post-war decades was devised under the aegis of shared “Britishness”, a unifying term little used in the United Kingdom. After Federation its qualities were increasingly considered distinctively Australian and actively celebrated.

But the 1970s brought two momentous changes.

The first was a profound recasting of the past. Previously, Australian cultural elites, while rarely hiding from our history’s often grim realities, viewed the building of Australia with pride – a pride that underpinned a strong, distinctive and unifying sense of national identity.

Now they framed a new imaginary history in which the Australia of the past was, according to Whitlam acolyte Phillip Adams, “the most remote, ethnocentric, inward-looking and changeless society on earth”, a barren, empty and grey wasteland, punctuated only by the craven fawning of British imperialists and the genocidal dislocation of the continent’s first inhabitants.

At the same time, as the previous national identity was derided, the ideal of a unifying culture was scorned with it. Australia’s strength, the revisionists argued, lay not in an encompassing sense of being Australian; rather, what was to be highlighted and encouraged was cultural difference, as if difference was a good in itself.

In its origins, the ambitions of this new multiculturalist approach were reasonably modest. Trusting implicitly in the continuance of the social code of tolerance built up over the decades, it assumed that code was so strong that it didn’t require protecting. Its primary focus was on supplementing the processes of ongoing migrant integration with some largely harmless commitments to maintaining cultural diversity via language programs and greater appreciation of European culture.

Al Grassby, the immigration minister in the Whitlam government, invoked the “family of the nation” metaphor when first announcing multiculturalism as a new policy in 1973. The Fraser government’s Galbally report – tabled in 10 languages to parliament in 1978 and definitively establishing the full panoply of multicultural policy and its trappings – went even further. It emphasised that multiculturalism was efficacious “provided that ethnic identity is not stressed at the expense of society at large, but is interwoven into the fabric of our nationhood”. Despite this, multiculturalism rapidly developed a momentum of its own that came to approximate a cultural revolution rather than continuance and improvement.

The term itself had originated in Canada in the mid-’60s and was soon adopted by prime minister Pierre Trudeau. The appeal for Trudeau was obvious as he struggled to cope with separatist pressures in Quebec while remaining cognisant of Anglophone Canadian views. The idea of multiculturalism shifted the focus from two to many, potentially easing the head-to-head confrontation between Quebec and the rest.

Its immediate use value for the more singular culture of Australia, where there were no separatist tensions, was less apparent. But it rapidly acquired great political appeal.

Nowhere was that appeal greater than in the ALP. Since 1901 the Labor Party had been more deeply invested in the White Australia Policy than any other major political movement.

In the opinion of its greatest speechwriter, Graham Freudenberg, it was the policy that had proved its most reliable source of voter support.

But the generation of party leaders who began emerging in the early ’60s – Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke, Bill Hayden, Don Dunstan and others – fought a long battle to remove the policy of racial exclusion from the party platform and replace it with the principle of non-discrimination.

Simultaneously, Labor’s previous heartland of support, blue-collar workers, chiefly located in the manufacturing industries, was beginning to dwindle and disintegrate. It was to be replaced with a new coalition of disparate groups, attracted by subsidies, public recognition and promises of social justice – and it did not take long for non-British migrants to be identified as one of the groups that could be wooed through lashings of financial and symbolic largesse.

The Liberal side of politics also had reasons to embrace the change. Early post-war waves of migrants, coming predominantly from Britain and the Balkan and eastern European nations caught on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain, tended to support the anti-communist Coalition.

By the mid-’60s however, those sources had dried up. Large-scale arrivals from Italy, Greece and, after 1967, Turkey and Lebanon skewed more in Labor’s direction, despite the Liberals’ record of encouraging migration, ending the White Australia Policy in 1966 and initiating a policy that focused solely on would-be migrants’ ability to integrate into their new nation. The Liberal Party’s unpopularity with increasing swathes of migrant voters in the ’70s was a key reason for its 1975 conversion to multiculturalism and the dramatic abandonment of the previous commitment to integration.

But what was most striking about the adoption of multiculturalism was the almost total absence of initial advocacy from the group directly affected, the migrants themselves.

Obviously, providing government resources to preserve ethnic cultures couldn’t help but appeal, most especially to ethnic community leaders, who enjoyed a sudden, startling accession to significant degrees of power, influence and status. This was, however, a response to policy initiated by successive governments, not a longed-for reform migrants had been pushing for themselves.

As author Raymond Sestito pointed out, “Australia’s political parties have been the initiators of multiculturalism, rather than responding to group pressure.” Historian Mark Lopez concluded similarly that multiculturalism “was developed and advanced in the name of ethnic groups, organisations and leaders, not by them”.

For the politicians’ part, the bidding war for migrant allegiance proved a trap from which it was almost impossible to escape. With organisations and ethnic community representatives created to facilitate the new policy, the electoral punishment any significant policy reversal would subsequently entail was feared, perhaps unjustifiably, to be severe.

But even more than the politicians, the group for whom multiculturalism became a sacred cause was the new elite class emerging to dominance in Australia from the ’70s. As with Indigenous self-determination, to question the policy soon became the secular equivalent of blasphemy. Under the threat of excommunication the policy, even if privately questioned, was almost universally publicly accepted. That was at least partly because there really wasn’t much reason to assail it.

In effect the consequences, however deleterious, for long proved relatively containable, a handicap rather than a cancer on the body politic. Disparaged though they may have been, the values of Australian life for which multiculturalism claimed credit but that actually predated it – tolerance and egalitarian openness – maintained an essential robustness, mitigating its harms.

However, new developments in more recent years and decades have dramatically increased the dangers that the policy’s original flaws always threatened.

The rise of virtual worlds, immersive media, social and otherwise, with global reach, now means it is possible to live at Lakemba in western Sydney while being for all intents and purposes in, say, Beirut.

As the Productivity Commission warned in 2016, “the ease of communicating with family and friends in the immigrant’s country of origin, and access to news and other media in their home language through the internet, has made it much easier for people who do not feel capable or have no desire to integrate”.

“To the extent that immigrants’ intent to integrate is decreasing,” the commission continued, that “raises an important issue about whether this provides scope for separatism that conflicts with, and/or has the ability to undermine, key norms and longstanding understandings that are important to the functioning of Australian society”.

To make things worse, the changes the Productivity Commission pointed to coincided with the spread of Islamic fundamentalism, which – in the name of maintaining religious purity – elevates separatism into an overriding religious obligation.

There were, and are, many Australian Muslims who are anything but Islamists and entirely reject separatism. Successfully integrated into the wider community, their contribution is there for all to see. But it would be foolish to deny that Islamist separatism presents threats on an entirely new scale.

That there were also intense ethno-sectarian pressures in the Irish Catholicism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is undoubtedly true. The priestly champions of Irish Catholicism in Australia pursued and insisted on a religious separation, demanding (with mixed success) that all Catholic parents eschew schools not devoted to an explicitly Catholic curriculum. Social, economic and political separatism was, however, largely non-existent. There was no ghettoisation, intermarriage rates were high, and the Labor Party and the unions provided membership alongside the wider Australian populace in mass movements that insisted, as best they could, on ignoring religious identity.

Additionally and crucially, even the most strident advocates of Catholic schooling never promoted a hatred of Protestants, much less a desire for their extermination. But, in contrast, it has become an integral part of Islamist preaching that, in the words of an Islamic text widely available in Australia, “vileness and depravity are inherent to Jewish nature”, accompanying “the Jew” just as “the shadow accompanies a man”.

The overall result is not just a separatism that tears at social cohesion; it is an active hostility to, and incessant attack on, the Australian community. And far from impeding those tendencies, the multicultural project legitimises them and bestows funding and authority on their promoters.

As those developments loomed, the Productivity Commission urged the government to “monitor social cohesion and integration trends” and take remedial action “if the proportion of the immigrant population not wishing to integrate rises”.

In reality, little was done by either side of politics – and Labor’s reliance on the Muslim vote made reform even more difficult.

Already in 1986, acting in the name of multiculturalism and mindful, according to a report in this paper, of “pressure from the growing local Muslim community”, Paul Keating was instrumental in blocking the deportation of Taj Din al-Hilali despite the latter’s viciously anti-Semitic statements. Subsequently acquiring citizenship, Hilali, one of the nation’s most senior Muslim clerics, unsurprisingly continued in the same vein, setting a trend that was subsequently copied in myriad mosques and prayer halls.

Keating’s decision as acting prime minister in Bob Hawke’s absence to grant permanent residency to Hilali in 1990 cemented a turning point. From this point the political die was cast and a policy whose risks were steadily materialising became untouchable.

Now it is time for it to be junked. Different cultures must be respectfully considered, not uncritically embraced. The illusion that diversity will bring unity, or even allow basic civility to survive, is as hollow as it is damaging.

Geoffrey Blainey put it well: “People need to feel they belong to their country.” As he said: “The multicultural policy and its emphasis on what is different and on the rights of the new minority rather than the old majority, gnaws at that sense of solidarity that many people crave.”

The Hawke government’s own FitzGerald report on immigration echoed these conclusions. Recommending that even the term multiculturalism be abandoned, it emphasised that “it is the Australian identity that matters most in Australia”. Unless the balance shifted from enshrining difference to promoting a unifying national identity, it was only a matter of time before the centrifugal forces that could tear Australia apart proved overwhelming.

The FitzGerald report shocked Hawke. He repudiated it and buried it in punishment for failing to provide his government with what it expected to hear. The news still may be unwanted. But this much is clearer than ever: closing our eyes and ears to multiculturalism’s failures is a luxury Australia can no longer afford.

Henry Ergas is a columnist with The Australian. Alex McDermott is an independent historian.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout