Freedom of speech has been the most fundamental of liberties since it was first defined in classical Greece. The problem is that most opinions are confused, few people are able to argue well and frustration erodes mutual respect.

What we need – more than ever in the era of social media – is a sifting and clarification of opinions and arguments, as a public good. How is this to be done?

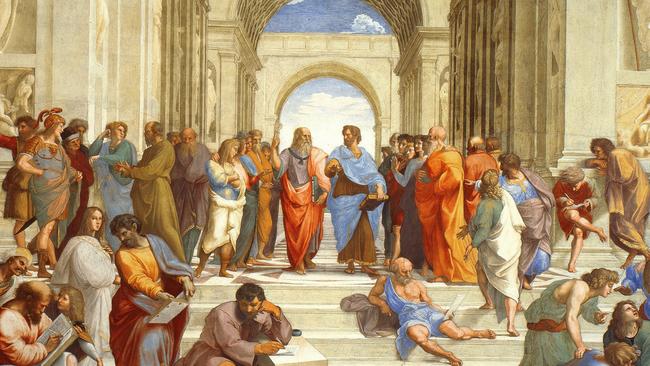

Education was the answer Aristotle offered. He did not mean indoctrination. He meant the training of young minds in understanding and thinking skills, as well as in practices conducive to responsibility and sound character. He is still worth reading on all these things – and updating for the 21st century.

But freedom of speech originated long before Aristotle. Kurt Raaflaub’s book, The Discovery of Freedom in Ancient Greece, is a good place to start, if you want to cross-examine the claim. Isonomia (equality under the law) and isegoria (equality of the right to speak) co-evolved with democratic institutions in Athens, over the century and a half between the reforms of Solon and the time of Pericles.

By the time of Pericles, the practice was called parrhesia – the right to say everything, ie, not to have to self-censor or avoid certain subjects. Such liberty came to be seen as the very definition of free citizenship in a democratic state. It’s what we are grappling with now when we ponder “hate speech”.

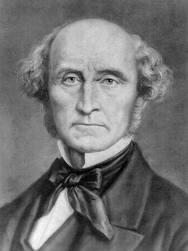

This liberty sits at the root of the freedom of speech championed by John Stuart Mill in his famous tract of 1859, On Liberty. Crucially, such liberty pertains to individual citizens, as the freedom to participate in complex debates under a set of laws and conventions that protect the liberties and safety of others.

It is not faithfully exercised by mobs who shout down speakers, invade classrooms and chant pernicious slogans without moral accountability. It presupposes an exchange of opinions, not the imposition of angry, abusive or intolerant positions.

Hence the traditions of decorum in parliaments and a speaker with a gavel who keeps order. Our universities, not least because they have for some time now been attempting mass education across an immense range of subjects, ought be the laboratories for productive debate and the exemplary exercise of parrhesia. Too often they appear to simply give militant students a free pass.

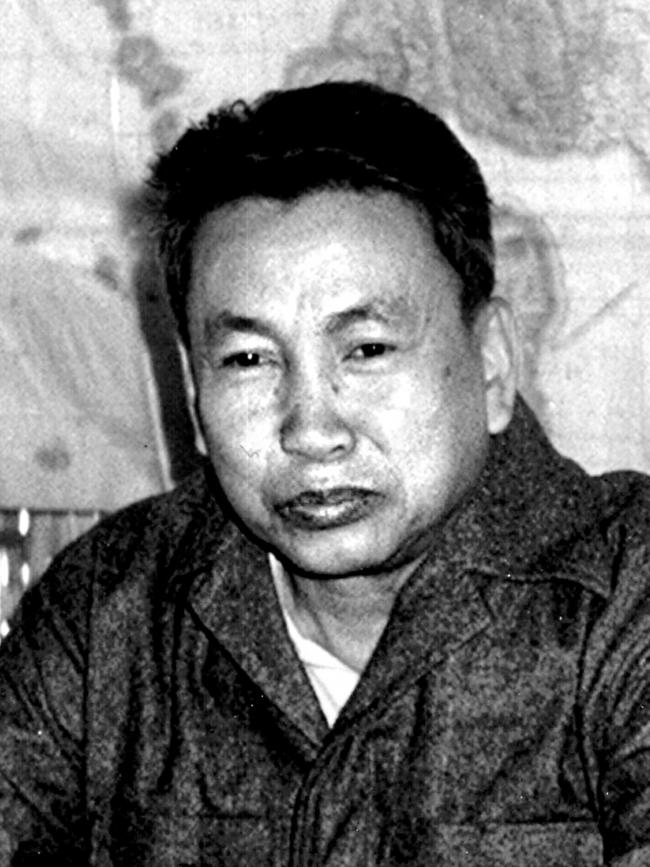

Almost half a century ago, in a tutorial on social theory, I had an exchange with a fellow student – an avowed Marxist-Leninist – when he sternly announced the need for “revolution”. I asked what he thought of those, such as me, who believed progress was best defined as the increased liberty and development of the individual. He retorted humourlessly: “Come the revolution, all those people will be shot.”

That was in 1979. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge had just done a lot of such shooting in Cambodia. I’ve never forgotten the exchange. But there was no exchange of blows.

Did that fellow have a “right” to his opinion? Does one, in present circumstances, have a “right” to the opinion, say, that Hamas is an organisation of freedom fighters that should be supported in “liberating Palestine from the river to the sea”?

We need to distinguish between the “right” to have or express an opinion and restrictions on any right to act on it. But that, in turn, requires careful thought about what we mean by “acting”. Demonstrating? Disrupting public traffic? Invading classes? Intimidating those who disagree? Organising funding for the cause? These questions themselves require parrhesia in order to be fruitfully debated.

This is where our universities have the most to contribute, in principle. I spent almost 20 years as a consultant and trainer in critical thinking skills and applied cognitive science – helping clients clarify and achieve working consensus on complex and divisive matters. The methods worked. Our universities badly need to sponsor workshops on contentious issues, using methodologies designed to develop common understanding, in place of angry polemic or dogmatically opinionated “resistance”.

Don’t have activists camped on the South Lawn with slogans, talking to one another and denouncing the administration. Don’t have them occupying the ground floor of Arts West in self-righteous puffery. Require them to participate with others of different opinions in workshops that actually address the issues in question. That would be education. That could generate progress.

If we’re not prepared, as a society, to build and maintain practices in which divergent opinions come together to deepen common understanding, under agreed rules of discourse, we imperil our liberal and democratic heritage. If we allow tribal and polemical opinion to govern public interaction, we undermine our shared liberties.

If we run scared of mobilised militants and fail to require certain standards of them, we betray our heritage. If we revert to authoritarian methods by attempting to suppress “disinformation” through government agency, we endanger freedom of speech itself.

The democracies of the classical world fell, in the end, to autocrats. The freedoms they had been built upon, however imperfectly, took centuries to reclaim. They are again in danger – around the world. They need to be defended not with tired rhetoric, but with energetic initiatives.

Of its nature, most freely spoken opinion is confused. This is especially the case where strongly held beliefs or interests are at stake. Clearing up such confusion requires not simply patience and maturity but methods.

The solution needed is not authoritarian crackdowns. It is structured debate, open exploration of assumptions, inferences and judgments. This requires anyone with a strong opinion to begin by asking themselves two questions: Why exactly do I believe what I do? And where could I be mistaken? It requires disinterested umpiring according to transparent rules.

Short of this, we end up in the Weimar Republic and in street brawls. Let’s not go there. We know where it leads.

Paul Monk is the author of a dozen books, including The West in a Nutshell: Foundations, Fragilities, Futures (2009).

Protests of many kinds are on the rise. This has made “freedom of speech” a hot topic.