Voice a chance to evolve culture of liberal democracy

But what has been missed in the debate so far is the extent to which the Uluru Statement presents a remarkable opportunity to rethink and revive liberalism, not repudiate it. As we consider the detailed proposals for the referendum, we need to keep some of the core principles of liberalism at stake in this debate in clear view.

Liberalism is a complex tradition, but central to its modern variants is the ongoing attempt to balance the competing demands of liberty and equality. In the latter half of the 20th century, the emergence of egalitarian liberalism – epitomised in the work of philosophers such as John Rawls, Jurgen Habermas, Martha Nussbaum and Elizabeth Anderson – put this reconciliation of liberty and equality at the heart of the modern liberal tradition.

A critical aspect of this tradition is the combination of the protection of the private autonomy of individuals with the public autonomy of citizens – a reconciliation, if you will, between John Locke and Jean Jacques Rousseau. This dual relationship between liberty and democratic equality is at the core of contemporary liberalism. You can’t have one without the other, and yet it also generates profound philosophical and political challenges.

One of the great challenges of our time has been to understand how deep structural forms of inequality – including those linked to legacies of historical injustice – can be addressed through this dual relation between democratic voice and individual dignity. Political activism has been a key element of this struggle. The great civil rights movement of the 1960s and ’70s, both here and in the US, although appealing to a vision of equal civil rights for all, also argued strongly for targeted measures to address deeply entrenched social and economic inequality. Martin Luther King’s famous 1963 book, Why We Can’t Wait, is a powerful example of this dual move – appealing to our common humanity, while also arguing for significant, direct measures (such as reparations and affirmative action) to tackle systematic racism.

More recently, another key move in contemporary liberal thought has been to explore the extent to which the recognition of certain group rights, as well as the accommodation of different forms of political and legal sovereignty – especially in relation to Indigenous peoples – could be among the pre-conditions for securing democratic equality. This is a hotly contested area, but by no means outside the scope of liberalism. Indeed, in Australia, it was a key aspect of grappling with the consequences of the Mabo decision. But what matters crucially is how these claims relate to other important liberal values.

I believe we should consider the claims at the heart of the Uluru Statement in the context of this rich tradition of democratic liberalism. Understood along these lines, the voice is not a repudiation of liberalism, but rather an expression of liberal democratic values now deeply informed by a true reckoning with our colonial past (and present). It is not a simple assertion of identity claims. It’s not a call for separatism. Rather, the voice is a call for democratic innovation in how we address our past and chart a better future. It is a call for engagement and the ongoing reconciliation of the democratic freedom of our Indigenous peoples with the liberal equality claimed by all citizens.

This also helps put claims about the voice somehow inserting race-based politics into our Constitution into proper perspective. First of all, it was, of course, successive Australian governments in the 19th and 20th centuries that approached Indigenous questions through the language of race and used it to discriminate against Indigenous peoples’ basic human rights and equal citizenship. The Australian constitution is suffused by that history of racial politics, and one we need to overcome. But second, seeing the voice as a contribution to democratic reform also focuses attention on the extent to which Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities are cultural and political entities, not racial ones. The proposed amendments make clear the voice will interact with parliamentary sovereignty, not stand above it. This is about democratising identity politics, not entrenching it.

There is another tantalising opportunity being missed in the current debate. It’s often said you can’t undo the past – and especially when it comes to the founding of a country. But the democratic vision embedded in the voice to parliament provides an opportunity for the ongoing reinterpretation of our country’s identity and future. Noel Pearson has talked about the three great pillars of Australia’s modern identity – ancient Aboriginal Australia, the legacy of British common law, and the deep multiculturalism of contemporary Australia. I believe there is a fourth: Australia’s democratic institutions and culture, and our ability, over the years, to innovate in the face of the great challenges we face. The referendum offers us the chance to draw deeply on this democratic tradition and forge a new future for our country.

Duncan Ivison is Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of Sydney and author of Can Liberal States Accommodate Indigenous Peoples? (Polity Press).

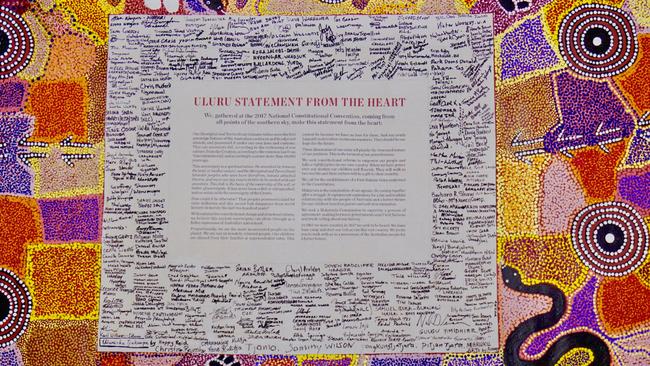

In the debate over the best means of implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart, concerns have been raised about the extent to which it will ultimately be divisive and entrench identity politics in Australian public life. Critics have appealed to the importance of preserving liberal democratic values in assessing the merits of the different proposals being considered.