The price you pay for messing with Vladimir Putin.

I first met Browder three years ago, late one night in London, while shooting a television program about the Russian gangsters who have turned Britain’s capital into the money-laundering powerhouse they now contemptuously call “Londongrad”.

Twenty minutes earlier, I’d received a text message which read: 2 Golden Square London W1.

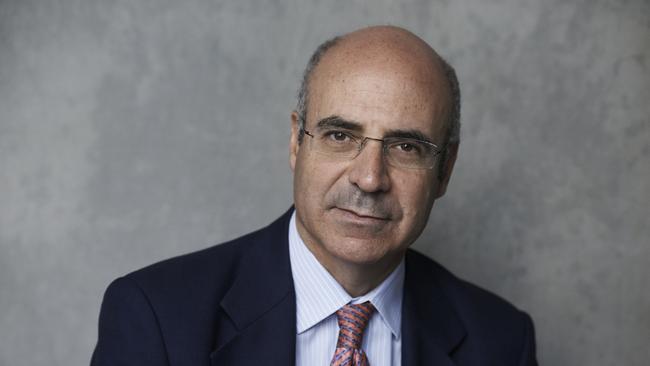

When the cab pulled up, Putin’s declared “Enemy No 1” emerged from the shadows, an unprepossessing figure flanked by a pair of black-suited bodyguards.

Browder doesn’t always travel with muscle but, when he’s meeting strangers, he doesn’t take chances. And he doesn’t like talking about the precautions he takes. “Well, I don’t go into exactly how I prevent my murder from happening,” he says drily.

This is not an exaggeration.

Lots of Putin’s enemies end up mysteriously dead, even in Britain from where this American-born financier now directs operations in an asymmetrical war against the Russian President.

Ever since his own lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, was beaten to death in a Russia prison after stumbling on a $US230m theft from the national treasury, Browder has systematically tracked the blood money from that crime to banks around the world.

Including, now, Australia’s.

The evidence is extraordinary: thousands of pages of bank documents handed to Browder by one of the Russian money launderers in England, a healthy 44-year-old who dropped dead in a Surrey lane while jogging, foam streaming from his mouth. A heart attack, ruled a heavily contested inquest.

Those kind of unhappy coincidences mean you never get your coffee from the same place twice.

Browder’s chief preoccupation is not staying alive but signing up every country to legislation that hits human rights violators where it hurts: in the hip pocket.

He has criss-crossed the globe charming, cajoling and shaming more than 20 governments into passing “Magnitsky laws”, named in honour of his friend, dipping into his own wealth to pay for it.

Browder says Putin is the head of a criminal empire, with a personal fortune of $200bn. He blames him personally for his lawyer’s death.

His anger at the failure of the Australian Federal Police to investigate the Russian money trail is palpable. “If the evidence we provided them didn’t rise to the standard of investigation in Australia but did in 16 other countries, that raises some very serious questions about what, if anything, would be properly investigated in Australia,” he says.

It is our shame.

Next year, Australia will enact an anti-corruption law named in honour of Sergei Magnitsky but our national police force can’t be bothered to investigate the crime that led to his murder. Their excuse? “The significant resources required to investigate the matter relative to other existing investigations and proceedings.”

Existing investigations like rifling through the underwear drawer of journalist Annika Smethurst for evidence to prosecute her for the crime of writing about proposed changes to the government’s surveillance powers.

Significant resources like the $400,000 the AFP spent on external lawyers in its failed High Court case against the same journalist.

What kind of cops hunt whistle-blowers and give a free pass to criminals?

Browder, like Smethurst, is not one to back away from a fight: “When you enter into a war with Vladimir Putin, there is no walking away.”

This is a totally driven man.

The AFP would do well to remember that.

The first thing you discover when you go out to dinner with Bill Browder is that he doesn’t eat. Or drink. Not from the restaurant, anyway. Too many of his friends have died that way — bad, agonising deaths, poison melting their internal organs: the calling card of the not-so-subtle assassins of Russia’s FSB spy service.