Up until that point, it was an article of faith that there was a trade-off between inflation and unemployment. A government could dial down the rate of inflation by accepting a slightly higher unemployment rate. By the same token, a lower rate of unemployment could be achieved by living with higher inflation. (It’s what economists call an exploitable Phillips curve.)

If the collapse in the relationship had only involved a new name, then it would have been neither here nor there. But the breakdown was critical to fracturing the belief in the Keynesian model of active demand management by government, even if it took many years for the message to be widely accepted. (Arguably, belief in the Keynesian model continues to influence bureaucratic thinking to this day, including in Australia.)

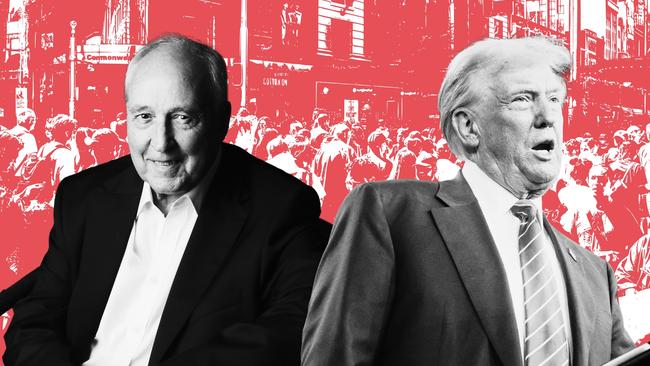

While it’s common these days to parody Paul Keating’s comment about the early 1990s – “it’s the recession we had to have” – the real intent of his statement is generally overlooked. The point he was making was that it was necessary to stamp out persistently high rates of inflation to enable the economy to reset on a sustainably productive basis.

Keating understood that the suite of supply-side reforms that had been enacted – think financial deregulation, removal of high tariffs, sale of government businesses, labour market reforms – would pay strong dividends over time.

Indeed, Australia experienced a purple patch of strong productivity growth and rising living standards after recovering from the recession of the early 1990s. Unemployment fell and treasurer Peter Costello was able to repair the budgetary position to the point that there was no government debt by the mid-2000s. Australia was poised for great things, particularly as commodity prices were moving strongly in our favour. No one was talking about stagflation.

If we fast-forward to this year, it may be time for a new term to describe what is an unexpected set of economic features – full employment, low economic growth, above-target underlying inflation, falling productivity and negative growth in per capita GDP. The term “per capita recession” is now widely used – a recession is defined as two successive quarters of negative GDP growth – but this doesn’t fully capture what is going on.

In order to unravel this puzzling bundle of characteristics, it’s worth reviewing what has been going on, including the government’s response to Covid and the aftermath.

A core issue is the slump in productivity, with the level of productivity now only at that achieved in 2016. According to the National Accounts, labour productivity fell by a massive 1.9 per cent in the year ending in the September quarter of 2023 and by 0.8 per cent in the year ending in the September quarter of 2024. This is the heart of the problem because productivity growth is the driving force of real wage growth and higher living standards. Unless we can understand why productivity in Australia is in the doldrums, we are incapable of devising appropriate policy responses.

To be sure, several other advanced economies have also experienced low or negative growth in productivity. But here’s the thing: the US is a standout when it comes to productivity growth, with the gap between average productivity in Australia and the US increasing over the past decade or so. The growth in labour productivity in the US has been 10 times higher than in Australia over the past 10 years, certainly on the raw figures.

James Thiris, senior research economist at the Productivity Commission, has taken a look at this “great productivity divide”, making the point that the two countries have slightly different approaches to measuring productivity and these differences should be taken into account.

The US figures focus on “the non-farm business sector”, which excludes the non-market sector, including education, healthcare and aged care. This non-market sector is largely funded by government and is known to be less productive than the market sector. Mining productivity also is much more volatile than in the rest of the economy.

Adjusting for these differences reduces the productivity gap between the two countries by about 20 per cent. But as Thiris concludes: “Even so, a sizeable gap still remains.”

Thiris considers some Australian characteristics to explain the gap, including the substantial JobKeeper program instituted during Covid to maintain the connection between employers and workers. In the end, the program propped up zombie firms and workers were discouraged from forming better job matches with other firms.

The strong surge in new entrants into the Australian labour market – much stronger than in the US – has also meant a relative glut of inexperienced, low-productivity workers. Over time, this effect may subside as workers acquire work-related skills and begin to hit their full potential.

Politicians often fall back on investment in education and training as a way of improving productivity. The reality is that the evidence on this link is unclear.

After all, there has been a significant ramp-up in the number of university graduates in Australia, but productivity has not risen in tandem. In fact, the proportion of 25 to 34-year-olds with a post-secondary degree in Australia is higher (56 per cent) than in the US (51 per cent).

Another way of looking at the productivity gap between the two countries is to think about what has been happening in the US and to draw comparisons with Australia. There are some very noticeable differences in the two economies that are important to understanding the divergence in productivity growth. These include capital investment, energy prices, technology, a flexible labour market, and taxation arrangements. These factors are interlinked.

Take energy prices, for instance. They are significantly lower in the US compared with Australia. For example, the price of natural gas in the US is close to 80 per cent lower than on Australia’s east coast.

Electricity prices are lower in the US, particularly in certain states. For energy-intensive enterprises, this environment is very attractive.

Technology is clearly playing an important role in driving productivity in the US – think Silicon Valley, AI and data centres. The combination of patient capital, huge rewards for success, and acceptance of failure contribute to the development and take-up of new technologies.

By contrast, Australia has lost its way when it comes to fostering productivity growth. There is a naive belief that the GDP can be divided up in different ways without affecting its growth.

In particular, the Labor government has sought to increase the labour share, in part by mandating or funding higher wages, and boosted government spending, assuming neither would damage productivity or per capita incomes.

The economic impact of the hyper-regulation of industrial relations introduced by Labor is downplayed. Having large migrant intakes has led to a capital shallowing that has had a negative effect on productivity.

With the election of Donald Trump, there is a real possibility that the gap in productivity between the two countries could further diverge. We must be prepared to learn the lessons.

The unexpected coexistence of high inflation and high unemployment that emerged in the 1970s prompted economists at the time to invent a new term – stagflation – to describe the situation.