Even though he is not formally inaugurated until January 20, some of the likely effects of his ascendancy are already apparent.

One of the key questions for us is: What will the Trump administration mean for the Australian economy? The answer is likely to be nuanced, with pluses and minuses. How the Australian government responds to the challenges of dealing with Trump also will play an important role.

It is worthwhile briefly outlining what a Kamala Harris win would have meant. Notwithstanding his strong previous centrist leanings, Joe Biden as President has overseen a strongly progressive and high government spending administration.

This would have continued under Harris.

The obsession with climate change that led to the passage of the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act provides for hundreds of millions of dollars in subsidies and tax credits for renewable energy and related projects. In a final pointless decision, Biden recently announced a target reduction of 61 to 66 per cent in emissions for the US by 2035.

Had Harris succeeded, the policy priority given to the climate would have strengthened – note here Harris’s Californian background – and various government agencies would have been given a free rein to impose costly regulations in the name of saving the planet.

It remains to be seen what Trump will do with the Inflation Reduction Act. Some of the spending is directed to projects in Republican states and the lobbyists will be busy trying to lock in spending under the act.

At a minimum, there is likely to be a significant scaling back and redirection of this spending. Trump will again pull the US out of the Paris climate agreement.

But let’s return to what Trump means for the Australian economy. Much of the discussion is about the prospect of the US imposing tariffs on imported goods and services from certain countries. Indeed, Trump has already foreshadowed the prospect of imposing a 25 per cent tariff on Canadian and Mexican imports. The reflex reaction of economists is to declare that tariffs are harmful to economic growth and are a tax on the poor. By distorting trade flows, tariffs can end up damaging the imposing country as well as driving up prices.

The one qualification is that because the US is such a large market, there is scope for tariffs to be absorbed by the exporting countries; it’s called the optimal theory of tariffs.

The reality looks a lot more complicated. For starters, Trump appears to regard tariffs as a political and geo-strategic weapon as much as an instrument of economic protection of local industries. For him, it’s really all about negotiation.

When announcing the potential tariffs that could apply to Mexico and Canada, he mentioned the flow of illegal migrants and fentanyl.

At this point, economists are way out of their depth when it comes to giving policy advice.

To be sure, the president-elect has some strange ideas about trade deficits and the mistaken notion that a deficit indicates that the US is somehow being robbed.

Note here that the US runs a trade surplus with Australia and trade flows between the two countries are relatively small.

Tariffs are only one instrument of industry protection, however. Many countries engage in supporting local industries through direct and indirect subsidies as well as through regulation and manipulation of the currency. It is misleading to focus on tariffs and changes thereto. Non-tariff barriers can be just as important, if not more important.

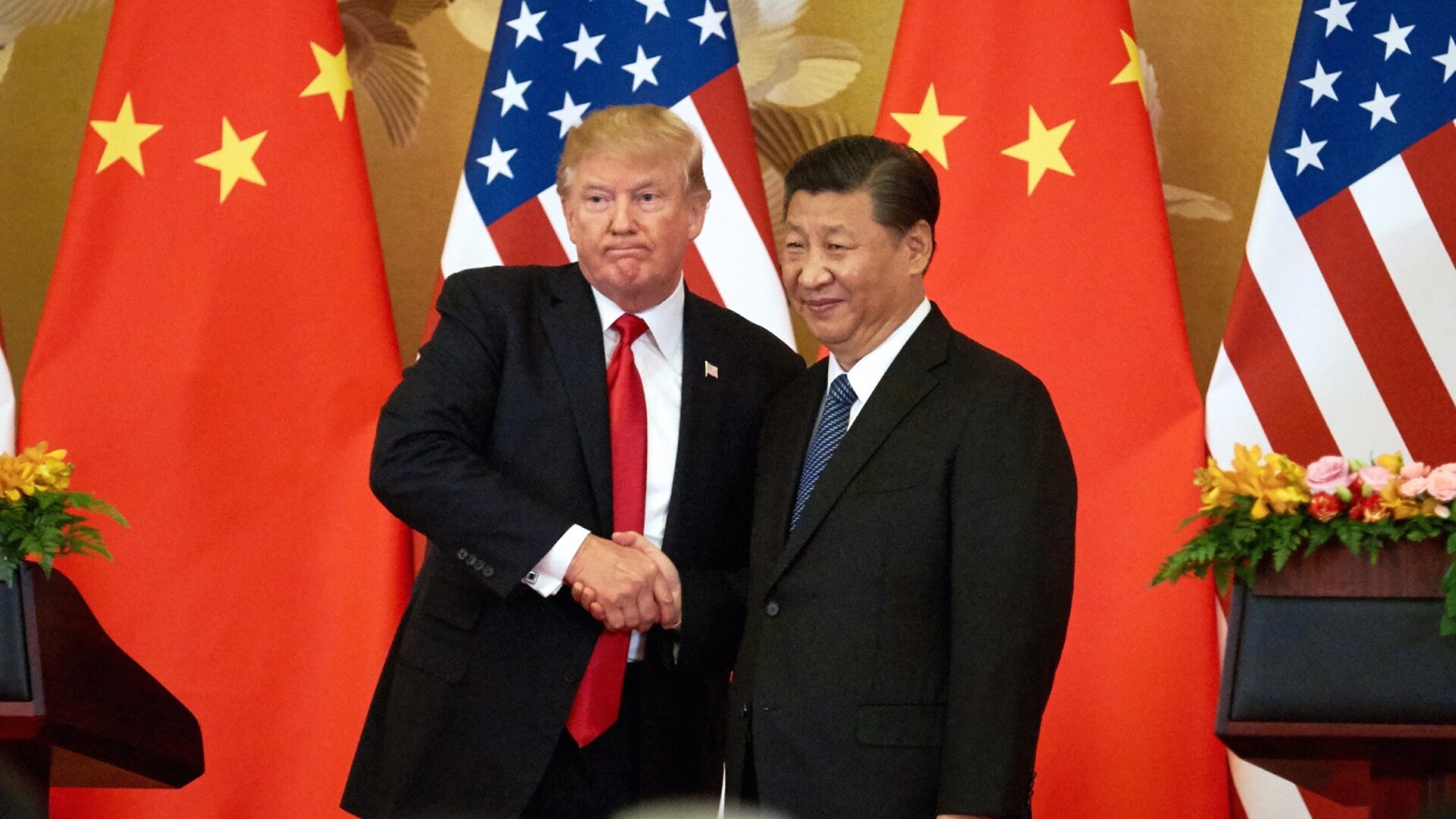

The elephant in the room in this discussion is China. Trump sees the rise of China as an economic superpower as diminishing the economic power of the US and eliminating local jobs in certain sectors.

During his previous term as president he imposed a raft of tariffs on goods imported from China, including motor vehicles. These tariffs were largely kept in place by the Biden administration.

Of growing concern in the US and other parts of the West is the rising dominance of China in the manufacture of electric vehicles. Not only are Chinese-made EVs considerably cheaper than those made elsewhere, their quality and technological capability are as good, if not better.

Coupled with government mandates in several countries that require more EVs to be sold, the pressures are now building on the viability of some of the large automotive companies in the West. This issue will likely come to a head under a Trump administration.

The challenges for Australia are indirect. With China as our largest trading partner by a substantial margin, any action by Trump that affects China will affect us. The best scenario is if Trump can negotiate some sort of settlement with the Chinese government that is likely to involve a winding back of state support for industry and a more freely floating currency.

Trump is also likely to disrupt the flow of international capital if he manages to reduce the rate of company tax in the US.

During his first term he achieved a great deal in lowering the tax burden on companies operating in the US, including by allowing immediate deduction of expenses.

US companies that held large amounts of financial assets offshore because of previously onerous tax arrangements were able to repatriate them without penalty.

During the election campaign, Trump declared he would reduce the rate of company tax in the US to 15 per cent. (He also intends to mandate the continuation of the tax cuts that were enacted during his first term in office.)

At this point, the rate of company tax in Australia looks hopelessly uncompetitive. Add in the cost of energy; it is much lower in the US, particularly in certain states, and the challenge for Australia will be to explore ways of making us an attractive destination for investment.

There will also be considerable interest in the ways Trump is hoping to tackle excessive government spending. He has enlisted the assistance of Elon Musk and former investment banker (and former presidential candidate nominee) Vivek Ramaswamy to take on the task. A new department, the Department of Government Efficiency, will be set up.

Rather than simply trim various government programs, the idea is that a root-and-branch analysis will take place of what drives government spending, particularly the actions of government agencies that effectively face no budget constraints. Attention will be paid to the underlying pieces of legislation and the need to alter or scrap them.

Trump has promised to rescind 10 regulations for every new one, which is likely to have profound implications for doing business in the US. Again, the Australian government will need to pay attention.

There is a real prospect of what economists called a Schumpeterian disruption, which is likely to turbocharge the US economy.

The fact is that productivity in the US is already far higher than here and has been growing strongly while it has been stagnant here. Australia can seek to be part of the new experiment or stick with its existing approach to policy that now looks increasingly out of step.

The most consequential event of 2024 from a global political, economic and strategic perspective was the election of Donald Trump as 47th president of the United States.