Yet even when that mobilisation was at its peak, expulsions were not on the university’s agenda. And on the rare occasions when they were mooted, it was for offences involving violence and the destruction of university property rather than for demonstrating, insulting the administration or engaging in strident debate.

The university’s reticence was hardly due to lack of pressure. Infuriated by the unrest, the state government, which controlled the university’s funding, repeatedly demanded action, with premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen naming the “ringleaders” to be expelled.

But those calls fell on deaf ears. As distinguished biochemist Ed Webb, who was deputy vice-chancellor (academic), explained, when “there are real issues in society that need to be addressed”, the university had an obligation to permit “individuals in the university to see that others are made aware of them”. Yes, that might provoke a hostile reaction; but fear of that reaction could never be a “reason for prohibiting the expression of opinions on things of great importance”.

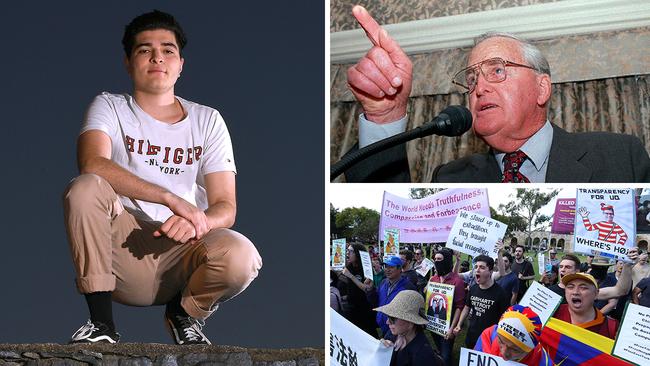

Five decades on, those lessons have plainly been forgotten. Instead, the university chose to commemorate the anniversary by initiating disciplinary proceedings against Drew Pavlou.

That Pavlou’s actions incensed the Chinese regime is entirely unsurprising. Organising protests in support of the pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong and against China’s repression of the Uighurs was bad enough; ridiculing the university’s cosy relationship with China by posting a “COVID-19 Biohazard” warning at its Confucius Institute can only have elevated the 20-year-old’s conduct into a hanging offence.

How many hundreds of thousands in Australian tax payer dollars has UQ's duumvirate of two Peter's burnt on their little ego trip vendetta against me?

— Drew Pavlou æŸä¹å¿— (@DrewPavlou) May 28, 2020

Keep it up boys, you're doing a hell of a job simping the Chinese consulate! pic.twitter.com/I8kEKafo3l

After all, as Charlie Chaplin said on releasing The Great Dictator, with its merciless portrayal of Hitler as “Adenoid Hynkel”, “let’s laugh them to scorn”, for mockery is the little person’s most powerful weapon against the jackboots and truncheons of tyrants.

That truth has been confirmed time and again. “The surest defence against Evil is extreme individualism, originality of thinking, whimsicality, even — if you will — eccentricity,” declared Joseph Brodsky, the Nobel prize-winning poet who, before being expelled from the Soviet Union, was incarcerated in its insane asylums for denouncing the Soviet regime’s madness.

One might have expected the university’s leadership to know all that. And rather than submitting Pavlou to months of uncertainty for the crime of satire, one might have expected them to focus on identifying the Chinese students who assaulted the pro-democracy activists, as well as on removing from his position as an adjunct professor China’s consul-general in Brisbane, Xu Jie, who blatantly breached the university’s code of conduct by publicly commending the assailants.

Facing expulsion over his anti-Beijing stand, student activist Drew Pavlou has launched a blistering 11th-hour attack on the University of Queensland, branding vice-chancellor Peter Hoj “a barefaced liar.â€

— Drew Pavlou æŸä¹å¿— (@DrewPavlou) May 28, 2020

Yep. He should be sacked and stripped of his AO!https://t.co/9mCITddGby

It is too easy, and too generous, to explain their decision to instead turn on Pavlou by pointing to the university’s dependence on Chinese students. No doubt, that figured in their minds; but the reality is that their predecessors’ dependence on Bjelke-Petersen’s government was far greater.

If that earlier generation didn’t buckle, it wasn’t because their choices were without consequence: it was because those choices involved matters of principle. There is, in that comparison, a crucial point. The problem is not that the leaders of our universities, in responding to incentives created by successive governments, have let themselves become vulnerable to the Chinese regime’s blackmail. It is that their ethical moorings are so fragile, the blackmail has every chance of success.

Unfortunately, they are not alone in leaving ethical standards behind. There is, as those with long memories will know, no doubt that if the administration had acted then as it has now, the university would have ground to a halt.

To say that is not to claim that things were better, nearly golden, in more or less remote times. Nor is it to gloss over the grievous faults of the students and staff who regularly packed the “forum” at St Lucia, as the campus’ main meeting ground was called. They were, on the contrary, blind to the crimes of the North Vietnamese and ignored the horrors their victory would bring.

But while they were almost wilfully naive, their commitment to freedom of expression was beyond question. The fact many of the university’s most influential activists came from the Catholic Newman Society and the Christian social movements, with their emphasis on sincerity, witness and engagement, merely made that commitment more intense.

Faced with cases such as Pavlou’s, they would have felt compelled to act. But, all too often, today’s staff and students feel no such imperative.

In part, that reflects the withering of campus life that had occurred even before the present lockdowns came into effect. With vast numbers of students working part-time, faculty routinely address empty lecture halls, eliminating the questioning and interaction that are central to teaching and to the formation of social networks.

The ever-growing number of foreign students, who struggle with English, and so tend to associate with their colingual peers, has compounded the social fragmentation, converting once bustling campuses into spiritual wastelands.

But if the commitment to free speech has waned it is also because students and staff can espouse the fashionable causes of the day without any danger to themselves. Far from risking prison sentences and hefty fines for demonstrating, as was the case in Queensland, they can indulge in protests about racism, refugees and “carbon pollution” basking in the glow of public approval. Goethe’s warning that “Man must win his liberty every day afresh” therefore means nothing to them, no more than Mill’s admonition that the freedom that really matters is that of those with whom we passionately disagree.

To that extent, Marx was right. Once they were comfortably dominant, he predicted, the bourgeois intellectuals would jettison the liberal values they had championed when they were an exiguous minority. Like the Anglican bishops with their 39 “articles of religion”, they would, at that point, far more readily scuttle 38/39ths of their principles than 1/39th of their income.

Marx could have had the University of Queensland in mind. But if an education is worth having, it is not because of the earnings it unlocks; it is because the ability to look at the world for oneself is the greatest gift of all. By pursuing Pavlou for doing just that, the university has accomplished, 50 years later, what Bjelke-Petersen could never achieve.

Fifty years ago this month, 200,000 people marched through Australia’s cities in the first Vietnam moratorium. The period leading up to the demonstrations had been tumultuous on campuses across the country, including at the University of Queensland. Already by 1967, opposition to conscription had merged there with protests against the state government’s restrictions on civil liberties, unleashing an escalating tide of agitation.