University of Queensland gets it badly wrong on China, free speech

UQ’s purgatory began last July during a peaceful student demonstration in support of the pro-democracy Hong Kong protesters and in solidarity with persecuted Uighurs in Xinjiang. The demonstrators were set upon by what observers said was a well-organised group of about 300 students and non-students, many shouting slogans in Chinese.

As some filmed the rally, the counter-demonstrators snatched the megaphones from the pro-Hong Kong and pro-Uighur protesters and sought to break up the rally. Punches were thrown.

Xu Jie, China’s consul-general in Brisbane, commended the counter-demonstrators for their “acts of patriotism”, while blaming the pro-Hong Kong students for “igniting anger and sparking protests from Chinese students”.

In a highly unusual step, Foreign Minister Marise Payne warned all foreign diplomats in Australia to respect the rights of free speech and peaceful protest.

Amid all this, the press reported that Xu had recently been appointed an adjunct professor at UQ. About a week later, a Sydney newspaper reported that Chinese officials had visited the mother of one of the students at the pro-Hong Kong demonstration — she lives in China — and that she then told her son his safety could be guaranteed only if he stopped his “anti-China rhetoric” and stayed away from other protests.

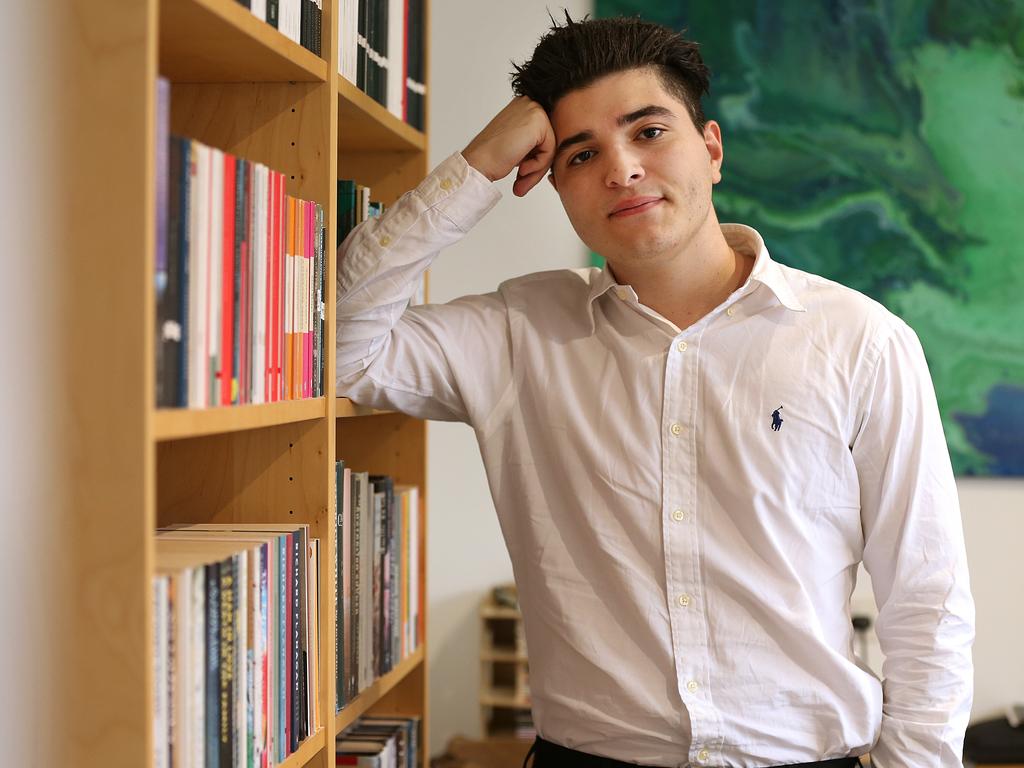

The story gets worse. In October, one student who led the Hong Kong-Xinjiang demonstration sought a court order against Xu, alleging that the consul-general’s rhetoric was endangering his life. The student, 20-year-old Drew Pavlou, ran successfully to become the student representative on the university senate to gain greater visibility for his China protests. He carried on a program of activism, including stunts such as posting a “COVID-19 Biohazard” warning in front of the university’s Confucius Institute, the local branch of a Beijing-funded “soft power” program offering courses in Chinese language and culture. (The US, concerned about the institutes’ tight links with China’s communist government, has banned any universities that host Confucius Institutes from receiving federal language-training funds.)

But keeping Beijing happy is essential to the UQ business model, and hosting a Confucius Institute is part of the package. Roughly 20 per cent of the university’s students last spring were from China, and international students pay much higher tuition fees than locals.

Furthermore, vice-chancellor Peter Hoj received a performance bonus of $200,000 in part because of his success in strengthening the university’s relations with China in ways that supported student recruitment. Hoj was committed. He not only allowed a Confucius Institute to be established on campus; he served for several years as an unpaid consultant to the Confucius Institute’s international board. At least one course jointly funded by the institute and UQ highlighted China’s emerging world leadership in, among other topics, counter-terrorism, human rights and the prevention of mass atrocities.

It was apparently intolerable that a student insulted an institution so august. UQ compiled a 186-page dossier of Pavlou’s alleged misdoings and summoned him to a hearing at which he faces possible expulsion.

The charges, according to those who’ve seen the confidential document, try to make trivial comments by Pavlou look sinister or attempt to infringe on his right to peaceful protest.

On Wednesday, Pavlou and his lawyer walked out of the disciplinary hearing, claiming the university was failing to follow its own procedures. The university denied these charges in a statement to the press.

UQ’s investigative zeal is embarrassingly selective. Administrators don’t seem to have spent much time, if any, investigating the students who disrupted the protest last July. Was there a link between the Confucius Institute or the Chinese consulate and the organised group that broke up a peaceful protest? How did the Chinese police know to visit a Queensland student’s family? Is there a Chinese effort to monitor and intimidate Chinese students abroad? Do Queensland students critical of Beijing face additional threats? That it somehow seemed more important to comb through Pavlou’s social media posts than to devote resources to questions such as these is the measure of how badly the university administration has lost its way.

The university has stoutly denied wrongdoing at every point. It asserts that the relationship with the Chinese consulate and the Confucius Institute is entirely proper, that Pavlou’s disciplinary case has nothing to do with free speech, and that the information released about Hoj’s performance bonus was partial and misleading.

UQ chancellor Peter Varghese — a distinguished public servant with impeccable credentials in Australia’s security establishment — has summarised the university’s position: “Boycotting China is not a sensible option. What we need is clear-eyed engagement which serves our interests and is faithful to our values.”

Varghese is not wrong about that, and UQ is not wrong to want Chinese students. The value of having them on campus goes well beyond money. They bring different and challenging perspectives that other students need to encounter.

But the lesson for other university leaders should be clear: the moral and reputational damage of mishandling a relationship with China can be ruinous. Open debate about topics such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and Tibet should not be suppressed simply because a foreign government objects. And if any students are to be expelled for violations of university standards, it shouldn’t be peaceful protesters but conscious agents of a foreign police state who abuse their university status to snoop on their peers.

The Wall Street Journal

The University of Queensland’s cosy relationship with China has ignited a firestorm.