History reveals that political dividends are immense from a trusting relationship between the Reserve Bank and the treasurer, that differences between the two are inevitable, and that disputes are loaded with dangers for both sides and should be avoided.

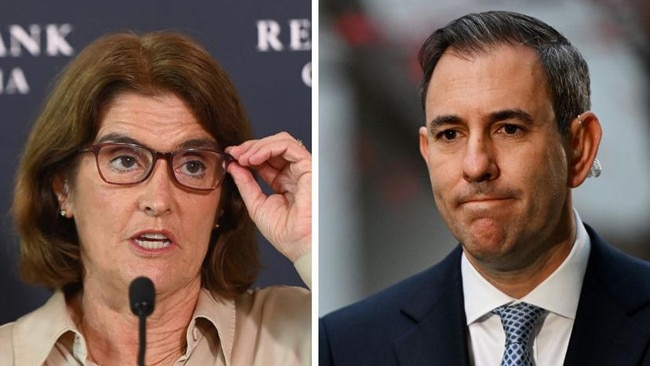

Jim Chalmers is not at war with the Reserve Bank but he does have sharp economic differences with the bank that are being mismanaged. The cost is mounting. At the weekend Chalmers tried to reconcile the contradictions, saying he was “working” well with governor Michele Bullock, that their goals were “aligned” – while refusing to endorse the attack on the bank by his former boss and treasurer, Wayne Swan, now ALP national president.

Swan’s assault on the bank, saying its interest rate stance was “putting economic dogma over rational decision-making”, will warm the hearts of the Labor faithful and many members of the Albanese government. Chalmers could only support Swan by triggering a full-scale crisis of confidence with the bank. That would have been huge folly.

In truth, these tensions are embedded in the model of Reserve Bank independence. Independence is the gift our politicians gave the bank, and it has now become essential in retaining the support of financial markets. But independence is neither absolute nor does it override the statute. It gives the bank greater powers but it also imposes greater pressures on the bank.

It creates a contradiction because the bank takes the monetary decisions but the government is politically responsible to the people for economic results. This guarantees the tensions. It means, as a consequence, the bank must retain the support of the political class and the political class needs to signal its confidence in the bank. They both need each other and both need to nurture independence. Otherwise, the model falls apart.

Describing the 1990s origins of independence, former governor Bernie Fraser said: “We needed to be a bit political to achieve independence and to keep it. But we got to the point where everybody – the markets, the treasurer, the government, the ACTU and even the Treasury – accepted the bank was best placed to make these decisions.”

Herein lies the truth: independence needs to be underpinned by consensus. Without consensus it disintegrates.

Paul Keating, in his famous December 1990s “Placido Domingo” speech, implied the bank was “in his pocket”, a comment that dismayed Fraser. “I chastised Paul about it,” Fraser said. Yet it was Keating who promoted a conditional independence for the bank. Keating and the Reserve Bank were united on one issue – the bonus from the 1990s recession was that inflation was broken and must stay broken.

But the transition to independence was fraught, courtesy of opposition leader John Hewson and his Fightback manifesto. Hewson wanted to impose a draconian 0-2 per cent inflation target that horrified both Keating and the bank. Reacting to reports that Hewson and shadow treasurer Peter Reith might remove him if they won the election, Fraser said: “I won’t go just to appease some dickhead minister who wants to put Attila the Hun in charge of monetary policy.”

Fraser told the author that if Hewson tried, he would have defied the government, forced Hewson into the never-used override provisions of the Reserve Bank Act with both sides tabling their cases before the parliament, and believed he could carry the day against Hewson.

It is paradoxical that in Chalmers’ reform of the RBA he initially favoured removing the government’s override power but abandoned this under across-the-board pressures. Keating always backed the override power, not on the basis it would be used, but because it was an ultimate instrument of leverage for a treasurer. For Keating, a treasurer had to possess the ability to influence the bank.

When inflation returned in late 1994, Fraser increased interest rates against Keating’s political interest. Fraser planned to go a full percentage point. Keating called Fraser and Treasury secretary Ted Evans to The Lodge. He got 0.25 per cent knocked off the increase – a concession, but Keating knew he couldn’t stage a showdown. The damage to the bank would have been too great.

The 1996 arrival of the Howard government and Peter Costello as treasurer saw the shift to full independence with the appointment of Ian Macfarlane as governor, probably the most significant appointment made by the Howard government in its 11 years. The Costello-Macfarlane agreement, released on August 14, 1996, recognised the “independence of the bank” and authorised an inflation target of 2-3 per cent with interest rate decisions to be announced by the bank.

Evans said of the compact: “It is most unusual for politicians to formally surrender power. It got the government out of interest rates and this is a big step.” Macfarlane said the agreement meant the bank entered a new world. Labor, stupidly, attacked the agreement. But when Kevin Rudd came to power 11 years later he kept the agreement.

Macfarlane understood the politics. As governor, he inspired confidence in markets, politicians and the media. That’s integral to being governor – but harder when the bank is lifting rates to knock an inflation cycle.

There are two stories that reveal the subtle application of power between Macfarlane and the Howard government. On August 28, 1998, Howard summoned Macfarlane to a meeting. He intended to call an election. The PM asked the governor to brief him on the outlook for the dollar and the economy. Macfarlane expressed confidence about the outlook. Nobody mentioned an election but Macfarlane felt this meeting was 100 per cent about an election. He issued no red light to Howard. Within days, Howard called the election. That’s trust, that’s how it works.

On May 20, 1998, Howard called Macfarlane to a meeting. The dollar was collapsing and the bank was under pressure to raise rates to stabilise the currency. Howard didn’t want the bank to lift rates and wanted to see the adjustment made via the exchange rate despite the fall in the currency this involved.

Macfarlane agreed with Howard; he felt there was no rationale to change policy. But their shared management of expectations was going to be vital. “We have to get the rhetoric right,” the governor told the PM. They discussed the messaging and agreed. It worked, interest rates were not lifted. Arthur Sinodinos said later he felt Howard’s position had helped steel Macfarlane in holding firm. In effect, they backed each other. Again, that’s trust.

Why is the bank so important? Because there is virtually no other powerful lobby for the anti-inflation cause in the nation. Ask yourself: If the politicians were setting interest rates, can you imagine how feeble would be the anti-inflation settings?

Does the bank always get it right? Of course not; witness the disastrous “forward guidance” from former governor Phil Lowe that interest rates would not rise till 2024. Indeed, Bullock is under more pressure now because of the bank’s past mistakes.

But the Albanese government has blundered trying to play clever politics. Chalmers’ use of the phrase “same objectives but different responsibilities” is the art of deception. He says beating inflation is the priority but the government typically avoids telling the public about the damage inflation does to the economic and social fabric and how it punishes the less well-off.

Inflation is the enemy of the Labor constituency but you would never know it. The Albanese government just offers cost-of-living relief and Labor thinks this blame-shifting to the bank will buy it political immunity. It’s wrong; the ploy is failing.

The public will hold the government responsible for the economy, and the government, by its equivocation and projecting differences with the bank, will merely look weak on economic management. Even a rate cut next February might not be enough to get Labor off the hook.