For too long both Ukraine and Russia, not to mention the US, Europe and Australia, have clung to unrealistic expectations about what is possible on the deadlocked battlefield as bloodshed, slaughter and misery unfold every day. What Trump is doing is shaking up conventional thinking and exploring the art of the possible in seeking a deal to end a war going nowhere.

This means taking a carrot-and-stick approach to secure critical compromises previously refused from both Volodymyr Zelensky and Vladimir Putin. The risk Trump has taken is to offer concessions to Putin first without being sure what he gets in return. But if, after this bold opening gambit, Putin refuses to reciprocate with his own concessions then Trump and Zelensky can simply say no to any ceasefire deal.

Putin is a far greater challenge for Trump than Zelensky, who wants peace and does not have the resources to continue the war indefinitely. Putin has the resources and the motivation to keep fighting. Russian forces are making small but steady gains, but these have come with a horrific death count and have delivered no larger strategic benefit. This is why Trump spoke to Putin before he spoke with Zelensky.

The central starting point of any ceasefire will be that the war is likely to be frozen roughly along the current frontlines in eastern Ukraine, give or take some kilometres traded through negotiation.

The question is what conditions Zelensky and Putin can agree to in relation to this.

The US approach, outlined by new Defence Secretary Peter Hegseth, is a bitter pill for Zelensky because it shoots down his unrealistic demand that any territorial concessions to Russia must be offset by a promise of NATO membership for Ukraine.

Putin began this war over his hostility towards Ukraine moving towards NATO membership and so it is – quite obviously – inconceivable that he would agree to a deal that includes a pathway to NATO for Kyiv.

But Ukraine clearly needs some form of security guarantee short of NATO to prevent an attack from Russia in the years to come. If Putin says no to this then a ceasefire deal is a non-starter.

Trump rightly says this is the responsibility of Europe, which needs to step up to guarantee Ukraine’s security without US troops.

This presumably means a peacekeeping force made up primarily of troops from European nations, which would be a more powerful deterrent than any toothless UN-sanctioned peacekeeping mission. Zelensky fears this is not enough of a guarantee from future Russia aggression, but he has little choice and, frankly, it is difficult to see Putin launching another invasion of Ukraine wjem French, German and other troops are stationed on Ukrainian soil.

Although a peace deal cannot include a future pathway to NATO for Ukraine, it is unclear if Kyiv would agree to Putin’s demand that it never seek one in the future.

Putin, in turn, cannot expect Ukraine to agree to any deal that does not at least provide it with some form of guarantee against a future Russia invasion.

This leaves the second key question of a territorial settlement.

Zelensky wants to trade the territory Ukraine now holds in Russia’s Kursk region for some of the land Russia holds on the frontline in eastern Ukraine.

Once again, the big challenge here will be Putin. In 2022 the dictator foolishly annexed four regions of Ukraine – Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia – even though Russian forces did not have full control of them at that time. They still don’t, yet ongoing Russian sovereignty over these regions is one of Putin’s key demands for peace.

Trump will no doubt try to seek a concession here from Putin, arguing that any settlement that includes ceding Ukrainian land to Russia which Russia currently does not hold is a non-starter.

The big picture is that if this US-brokered deal comes off, Russia will hold roughly 20 per cent of Ukrainian territory.

This is an imperfect outcome for both Ukraine and the West.

But it is often forgotten that before Putin’s invasion in 2022, Russia and Russian-backed separatist forces already had effective control of 14 per cent of Ukraine. To lose an extra 6 per cent of land over a three-year war against a far larger and more powerful enemy would hardly be a crushing defeat for Zelensky under the circumstances.

But Hegseth is right when he says it is “unrealistic” to expect Ukraine to be able to reclaim its old borders and that without compromises the war will simply continue indefinitely.

For any ceasefire to work Trump still needs to extract key concessions from Putin on territory and on Ukraine’s security guarantees. If Putin refuses to give ground then the US should oppose any ceasefire.

It is too early to know if Trump will succeed, but his direct intervention has opened the first genuine path to ending this horrific war.

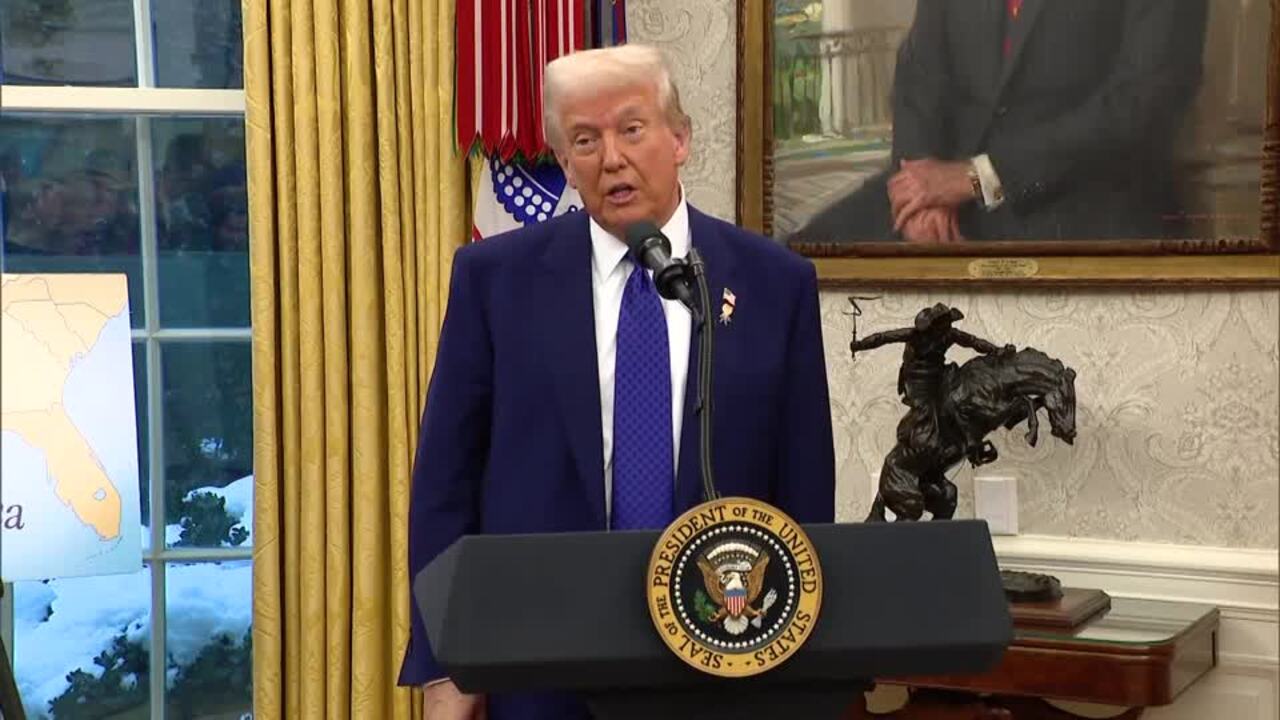

Donald Trump’s push to end the war in Ukraine is a triumph of pragmatism over wishful thinking, which is what is needed right now to end the three-year conflict.