Torment of the past demands voice for future, says Thomas Mayo

I am not using emotional blackmail to convince you to vote Yes – a criticism I have heard from agents of the No campaign. But emotional motivation can coexist with reason. This is logic at work, based on the clear evidence of failure in the trials and errors of policy, past and present.

As a pragmatist, I am a supporter of constitutional recognition through a voice to parliament because I want to see solutions. I believe many Australians will share these practical motivations. They will vote at the referendum based on their understanding that saying Yes will improve the lives of Indigenous people. This is understandable. Who could disagree there is a problem that we as a nation have a responsibility to address?

Today, Indigenous Australians are only 3.2 per cent of the population yet we are 12.5 times more likely to be imprisoned as an adult and 26 times more likely to be imprisoned as a child. Our mortality rate is 1.7 times higher, with 61 per cent of deaths before the age of 65.

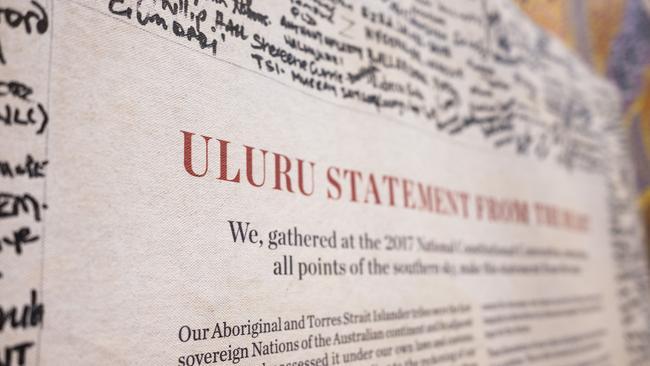

These are some of the disparities that inform this powerful passage in the Uluru Statement from the Heart: “Proportionately, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.”

This highlights two things. First, that we are a distinct group of Australians with a unique connection to our country and a rightful place that has yet to be recognised. And, second, that as a distinct group we have some distinct challenges.

I was a part of the constitutional dialogues, one of 12 around the country, in the lead-up to the endorsement of the Uluru statement. With about 100 fellow Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at the dialogue in Palmerston near Darwin, with participants from the Northern Territory region north of Gurindji country to the Tiwi Islands, we discussed how Indigenous representative bodies, or voices, had been established many times in the past and always, on changes of governments, these bodies were defended or repealed.

We also learnt about the good work representative bodies did and how their problems, as all organisations will have from time to time, were amplified by hostile politicians. If the voice is only legislated, we know from past experience that we would be setting it up for silencing at the whim of a future government.

Another lesson that informs us of the need for a voice is to consider what happens when Indigenous people don’t have one. Soon after the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission was repealed, hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for vital community services was cut. Less money reached the people in the communities who needed it while more money made it in to the pockets of those who didn’t.

We saw the Racial Discrimination Act repealed as the Northern Territory intervention rolled an army of bureaucrats through remote Aboriginal communities at incredible expense. And we know today that for all of the extreme measures and the ongoing canvassing of Indigenous people’s failures, the policies imposed without a voice have made matters only worse.

What you see in Alice Springs today is a result of the failure of our democracy to hold politicians responsible for their decisions made in Indigenous affairs. Each time, Indigenous people have sounded alarm bells but nobody was listening. A voice to parliament will turn this around. The status quo will not. All sides of politics agree that decisions about Indigenous people should be made with them, not about them, for the best results. The difference is in how accountable the parliament and government should be to do it as a matter of course.

The Albanese government is taking up the practical approach pitched by Indigenous people from across the nation in the Uluru statement.

The Coalition is taking its own direction, one that has been proven to fail. The contradictions are clear for anyone ready to look past the outdated rhetoric. We should ask ourselves why the Coalition would want to avoid a constitutional change that merely provides Indigenous people with the certainty of a say – no right to veto, no third chamber in parliament. What do they think is wrong with greater transparency in Indigenous affairs? Why support a legislated voice that they can repeal, and not one established by the will of the Australian people?

We must beat the tactics of confusion being deployed by the No campaign. We should share with fellow Australians that at this referendum we will be considering a simple proposition: to recognise Indigenous Australians by accepting a generous offer to share their history and culture as part of who we are as a nation, and to do it in a way that provides the practical means to improve outcomes in Indigenous communities.

Thomas Mayo is a Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man. He is a board member of Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition.

For most Indigenous Australians, we seek constitutional recognition because of the love we have for our children and our country. After all, if this referendum fails, it will have detrimental impacts on the health and wellbeing of our families and communities for generations. If it succeeds, we know they will enjoy better lives.