Top 20 economies can’t all be stupid in embracing nuclear

Most Australians will regard this as nonsense, but the Prime Minister’s main problem is Energy Minister Chris Bowen’s almost unhinged criticism of nuclear has backed Labor into an immutable opposition to this emissions-free energy source. The fact Australia is the only top 20 economy that doesn’t use nuclear has gone over the heads of the Labor leadership. Other countries can’t all be stupid.

Bowen’s recent article “Proponents of nuclear power are peddling hot air” (24-25/2) reveals something equally startling: the shallow reason he opposes nuclear power: that it is “being used as a distraction and a delaying tactic” to retard take-up of renewables. This worrying and clearly untrue assertion ignores the fact nuclear can operate as a firming agent to assist renewables when the sun doesn’t shine or the wind doesn’t blow. Far from being a replacement, it’s a carbon-free natural ally of renewables.

Bowen fails to appreciate the worldwide renaissance of nuclear after the setback to public opinion caused by the 2011 Fukushima tsunami event in Japan. Global concern about climate change is supporting the role emissions-free nuclear must play in assisting renewables to replace fossil fuels. Boosted by the support of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and even some green parties such as Finland’s, which defines it as “sustainable energy”, new nuclear plants are being built all over the world. A good test is the rising demand for uranium (their fuel) and the price, from $US24 a pound four years ago to $US104 today.

Sweden’s climate policy action plan to reach net zero by 2045 says “expanded nuclear power is the single most important measure” to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. At the recent COP28 climate conference in Dubai, 22 countries undertook to triple their nuclear generation by 2050.

To support his “distraction and delaying tactic” accusation, Bowen relies on a claim in the CSIRO’s 2023-24 GenCost report that nuclear is too costly and takes too long to build. The report uses nuclear cost estimates provided back in 2018 by GHD, an engineering and environmental consulting firm of good repute but no expert on nuclear costs. This estimate was given at the time for the GenCost report in 2019-20.

Tony Irwin, a nuclear engineer who has run a nuclear plant in Britain and is an expert on new-technology small modular reactors, says: “Every nuclear inquiry since that 2019-20 GenCost report has questioned the accuracy of GHD’s analysis of nuclear costs.”

Ian Hore-Lacy, a fellow of the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, told the house environment and energy committee in 2019 that GHD’s estimates were “astronomically high and unjustifiable”. CSIRO is still using that much-criticised 2018 estimate in its latest GenCost report.

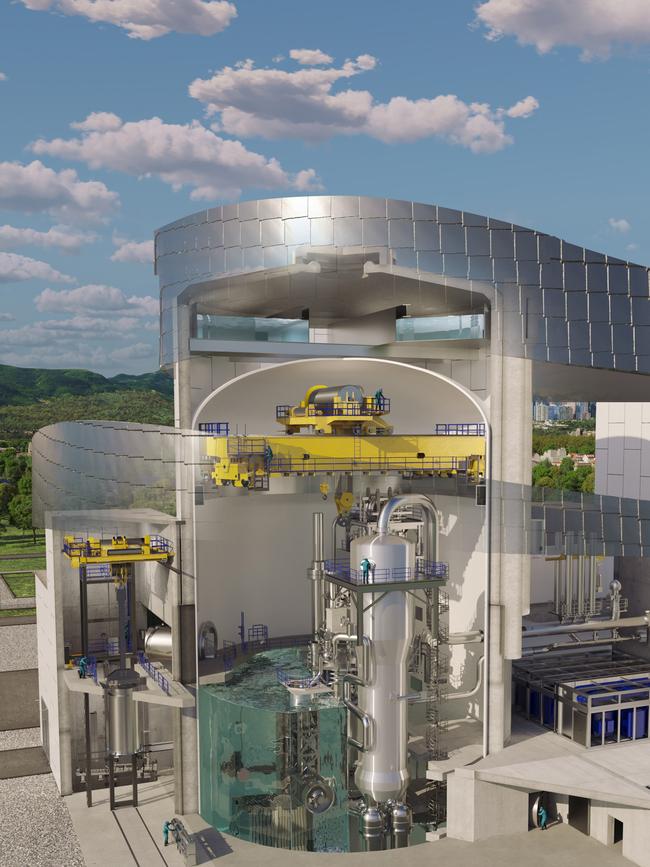

The International Energy Agency states that the cost profile of SMRs benefits from the high level of standardisation in their construction and their modular design, which enables two, three or more SMRs to be located together to generate the power required.

In the latest GenCost report CSIRO also points to the recent cancellation of a six-module SMR project in the US to support its claim that SMR costs are too high. Developer NuScale had planned to construct the SMR facility in Idaho for a group of 28 utilities. The estimate of net cost of electricity for this facility rose from $US58 a megawatt hour in planning stages to $US89/MWh before construction began.

This is no surprise for a first-of-kind project. The cost escalation allowed the utilities to resign from the venture, causing the project to be mutually terminated. But the cost was still a fraction of the GHD “analysis” in the GenCost report of $636/MWh ($US445) – an amount five times higher.

It would be an exaggeration to conclude the cancellation of one project means SMRs are non-viable, especially when 18 countries including Canada, an economy similar to Australia’s, are in various stages of developing them.

Another flaw in the 2019-20 GenCost report is the claim, devoid of analysis, it would take 15 years to construct an SMR in Australia. Based on overseas experience and adjusting for local conditions, Irwin calculates SMRs could be built here in 10 years, to be available in the early to mid-2030s – the same time span projected for offshore wind projects.

With so much evidence that the world’s economies are backing nuclear energy to reduce emissions, the case at least for considering nuclear for Australia overwhelms Bowen’s flimsy whim that it is “a distraction”. Now the Opposition Leader has put nuclear firmly on the political agenda, voters will get to decide next year whether Australia adopts it.

Tony Grey is a former chairman of the Uranium Institute, now the World Nuclear Association.

Peter Dutton’s declaration that the opposition will back nuclear energy to enable the country to meet its carbon net-zero targets has drawn a predictable response from Anthony Albanese that “nuclear power can work overseas and does work” but “doesn’t stack up for Australia”.