Too much peace can bring its own dangers

This week marks 80 years since Europeans emerged blinking from the rubble and ashes of their ruined continent into a new world of peace.

That distant age of fire and fury – of rockets raining down on London, of nuclear bombs, of France as a war zone – is alien almost beyond imagining.

For all that our world has grown darker in recent years, many of the problems pressing most urgently on us are not those of war but of peace.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Western societies were still the beneficiaries of a world forged in war. Every citizen was imprinted with a vivid and immediate lesson in the high price paid on Normandy beaches and in shattered cities for democracy and freedom.

It is our dangerous privilege to live in a time when those terrible lessons are slipping out of living memory. Many of the pathologies of modern civilisation – furious squabbles over trivia, an American President who toys with the prospect of invading Greenland, the disturbing fetish of European electorates for strongmen and extremists – are symptoms of a society that is beginning to forget.

To jaded moderns who have watched MPs debase themselves on reality TV and the US President shimmy his well-upholstered form to the pounding beat of YMCA, the generation of post-war politicians startles with its seriousness.

But that earnestness was instilled by first-hand experience of something few alive now properly grasp: the teetering fragility of liberal democracy. A generation of men and women had watched the whole edifice of European civilisation almost burn down in front of their young eyes. They took that civilisation very seriously indeed.

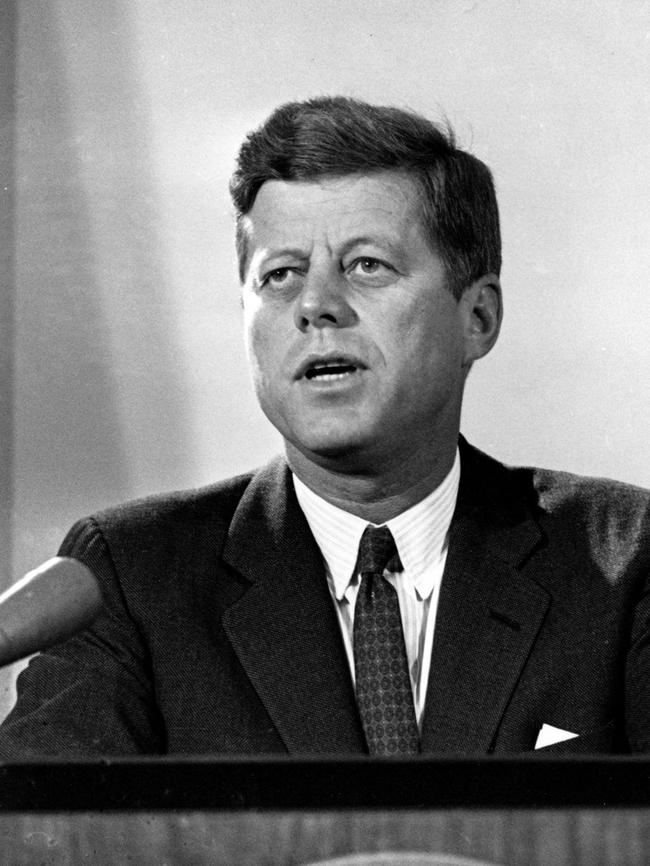

John F. Kennedy was only the most prominent war hero elected to high office in the decades after the war. When his ship was sunk in 1943, he swam four miles to safety, dragging an injured comrade by gripping the man’s lifejacket in his teeth. Few modern Westerners are qualified to say how an experience such as that rearranges a person’s perspective on human affairs. But political autobiographies were once littered with such anecdotes.

As political scientist Francis Fukuyama writes in his superb book Political Order and Political Decay, nations fighting existential threats have a strong incentive to become more unified, more efficient and more meritocratic.

One of the proximate causes of Britain’s Northcote-Trevelyan Report, which established an apolitical, merit-based civil service, was our country’s catastrophic experiences in the Crimean War.

Similarly, the high-stakes wars fought by Frederick the Great’s Prussia compelled its leaders to start staffing its bureaucracy with qualified professionals as well as aristocratic dilettantes. When a country is fighting for its survival, the cost of appointing mediocrities to positions of power becomes intolerably high.

To have faced down an enemy is a powerful thing for a country – World War II’s continued pre-eminence as a theme of British identity is a lesson in the way existential conflict binds a nation.

Before the US civil war, Americans tended to say “the United States are”. After, the more common phrase was “the United States is”. Ukrainian national identity is presently undergoing a similar transformation. And war provides more than unity.

Psychologist Michele Gelfand has shown that societies with a recent history of crisis become “tighter”; that is, more socially conforming, more polite, more orderly and more law-abiding. “Groups that deal with many ecological and historical threats need to do everything they can to create order in the face of chaos.” We think, perhaps, of Britain and the US in the 1950s.

None of this is to endorse the grisly and dyspeptic line of analysis that holds that all modern society needs is “a good war” to toughen up the decadent youngsters. That such ideas can be entertained so casually is itself a pathology of peacetime. Only those who have never seen young men die on the battlefield can think such thoughts.

The point is merely that long decades of peace have presented Western societies with some unaccustomed problems.

Fukuyama writes about the divergent trajectories of Europe and Latin America.

In the middle of the 18th century, both were politically similar: autocratic oligarchies controlled by wealthy elites. Europe then underwent two centuries of violence: the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, the revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War, before pitching into the conflagrations of the 20th century.

Since 1945, most western European nations emerged as strong, unified, law-abiding, socially mobile democracies.

By contrast, Latin American countries – more peaceful by virtually every metric during the same two centuries – were more polarised, undemocratic and corrupt. Those problems, Fukuyama suggests, were partly bred by the aimlessness and stagnation that attends peace. It is no accident that those issues may now seem familiar to modern Westerners.

War – this bears repeating – is not virtuous. Societies are ground down and destroyed by it. Few men at the Somme would have been much cheered by reflecting on the improved adherence to social norms that characterises recently traumatised societies.

The point is only that an extended peace brings its own problems: disunity, inequality, incompetence. They are infinitely more benign than mechanised slaughter. But tricky nonetheless.

Refusing to forget the horror of World War II and the incalculable preciousness of the ensuing peace is an important part of the answer.