And it is that indifference – which ensures one can buy goods in a shop, purchase a home, or seek the protection of the law, without race, sex or religion getting in the way – that creates the space for individual difference, providing freedom’s indispensable foundation.

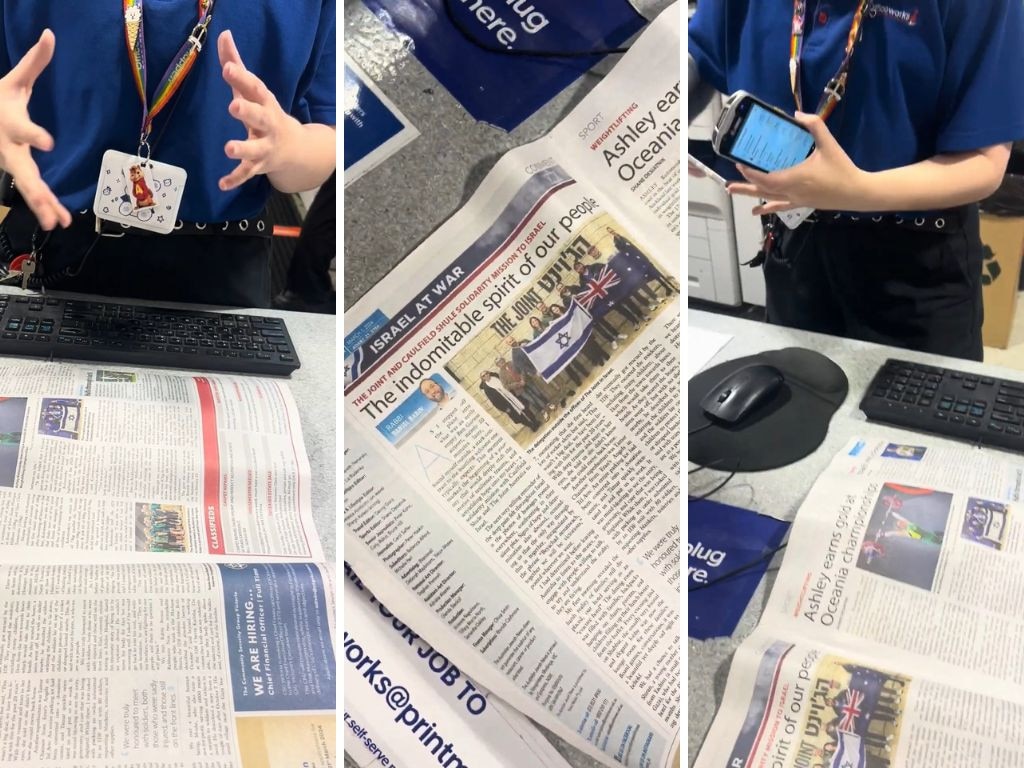

The incident at Officeworks, where an employee repeatedly refused to serve customers because they were Jewish, is therefore more than an outrage; it is emblematic of a decay in the fabric of Australian life.

Nothing better highlights the rot than Officeworks’ paltry response. That its sanctioning of the employee fell short of the lightest stroke with the tiniest feather-duster is bad enough. Even worse, however, is the manifest insincerity of its apology.

At the heart of the apology is the following sentence: “We confirm that we have taken this matter extremely seriously investigated the matter at the time and took appropriate disciplinary action (sic).” As the myriad grammatical errors would be obvious to any high school student, one can safely assume that Officeworks’ managing director, who signed the document, did not even bother to read it.

Attempting to then fob off the victim with a $100 gift voucher – as if being subjected to blatant anti-Semitism was just an ordinary commercial mishap – underscores Officeworks’ refusal to properly engage with the issues the incident raises.

Those issues need to be viewed in their broader context. It is the distinguishing feature of modern society that our lives depend on countless interactions with strangers whose backgrounds and beliefs bear no relation to our own.

In the pre-modern world, wrote historian Ernest Gellner, “a man buying from a neighbour was dealing not only with a seller but also a kinsman, a potential supplier of a bride and a fellow defender of the village”, with all those strands influencing their transaction. Modernity, by contrast, “dramatically narrowed the factors considered relevant to commercial transactions, making them largely freestanding”.

Thus, in entering a store, we expect to be treated solely as a customer – all of our other attributes being set aside – just as we expect the store to supply us with goods and services so long as we pay their price.

And underpinning those expectations is the conviction that a shared interest in the transaction proceeding, and not our views on the day’s burning issues, will shape our relationship.

Adam Smith saw that narrowing of the factors affecting commercial transactions as a momentous advance. More forcefully than any of his predecessors, he hailed the fact that in “commercial society”, “it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest; we address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love”.

That, Smith stressed, unlocked vast efficiencies, both by expanding the market and by slashing the information required for daily living – consumers no longer needed to know whether a merchant was a fanatical Whig or a zealous Tory, a Protestant, a Catholic or a Jew. But even more importantly, the specialisation of roles channelled potentially incendiary conflicts into the political arena, where they could be addressed by well-defined processes, rather than allowing them to poison social life.

Smith was therefore convinced that “commercial society” could help curtail “the most odious of all distinctions, those of religious prejudices, which, more than any other, render the inhabitants of the same country more hostile to one another than those of different countries ever are”.

What Smith ignored, however, was that the interests of “the butcher, the brewer, or the baker” in promoting civility between people “without any mutual love or affection” might clash with the passions of their employees. Yet that tension became apparent when the development of large-scale retail outlets meant shop assistants had to engage with an ever-wider range of customers, including many whose attributes they disliked.

It was precisely so as to deal with those tensions that Paris’ Le Bon Marché, the pioneering mid-19th century department store, put enormous emphasis on training its employees to be unfailingly civil. Backing that up, the formidable Madame Boucicaut, who – despite never learning to read or write – steered Le Bon Marché’s rise to global fame, promptly dismissed any employee who deviated from its code of conduct, thereby assuring patrons that they would be well-served.

Madame Boucicaut was no political theorist. But her actions exemplified the insight Hannah Arendt later articulated when she argued that by rigorously enforcing the rules and norms of civility, the exercise of legitimate authority plays as vital a role in preserving the benefits of a free society as the wielding of brute force does in perpetuating its totalitarian rivals. Far from being adversaries, she said, freedom and authority march hand in hand; and when legitimate authority collapses, the bullies and the brutes invariably seize its place.

That, in area after area, is what we are witnessing in Australia: a crisis of authority that is cascading into a crisis of the civility and tolerance Adam Smith taught us commercial society could bring.

The signs of crisis are pervasive. Our classrooms, surveys show, are out of control, with devastating consequences for students’ education. At the ABC, egregious breaches of its code of conduct incur a gentle slap on the wrist – if that.

As for the universities, their leaders combine spinelessness with incompetence. Just last week, to take but one example, the ushers at a University of Melbourne graduation ceremony adamantly refused to intervene when a number of students donned keffiyehs, waved Palestinian flags and shouted anti-Semitic slogans – despite all of those being glaring violations of the university’s regulations.

And now Officeworks has added itself to that list. Yes, its parent company, Wesfarmers, donated $2m to the voice campaign; but its displays of conspicuous virtue plainly do not extend to upholding civility and sanctioning anti-Semitism.

It is, in the face of those developments, scarcely surprising that there are intense pressures to not only preserve but strengthen the Race Discrimination Act: when the private structuring of social relations breaks down, incivility’s victims naturally turn to the law, with all of its shortcomings, to fill the vacuum.

The challenge, for those of us who feel uncomfortable with that approach, is not to cavalierly dismiss those pressures; it is to develop credible alternatives. Rehabilitating, and insisting upon, the exercise of legitimate authority would be an excellent place to start.

Toleration, it has often been said, is a right to difference. In reality, however, it is primarily a right to indifference: that is, a right to be treated, in a broad range of social relations, as if race, sex and religion were irrelevant.