Sacking Officeworks employee will achieve nothing

A dismissal could demonstrate a serious consequence for an egregiously offensive action.

But it will, most definitely, also turn her into a martyr, a poster child for the anti-Semitic left. So, let’s pause and think.

If anyone thinks sacking this employee will settle this issue, they haven’t been paying attention to what has been going on in schools and homes, universities and workplaces, and courtrooms too.

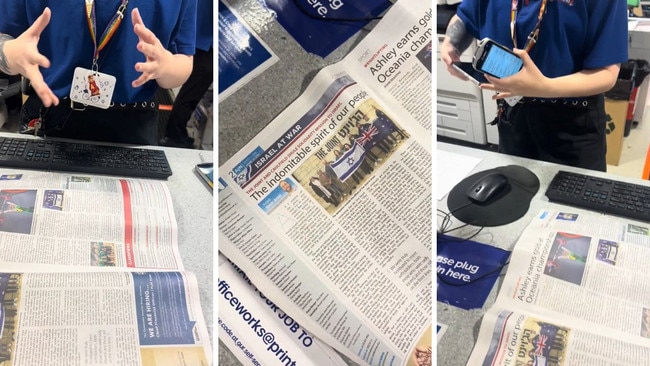

Caught on camera, the young woman’s language is a clue. The staff member, in her early 20s, can be heard telling the Jewish customer who wants to laminate a page of The Australian Jewish News featuring his trip to Israel, that she is pro-Palestinian and “I’m not comfortable doing that”. She says it’s company policy that she doesn’t have to do a job that makes her uncomfortable.

There is an opportunity here to consider something fundamental: how does a woman in her early 20s come to think that because she feels “uncomfortable” she has a right to refuse service to a Jew? Answering that question is much harder than issuing a dismissal notice.

Harder because blame extends well beyond this deluded young woman. It reaches into management ranks of Officeworks, into the boardroom of its owner, Wesfarmers – and into every company where workplace codes routinely use touchy-feely language that may lead an employee, especially a young one, to imagine that if something, or someone, makes them feel uncomfortable they can object.

Officeworks’ Print and Copy Terms and Conditions state that a customer must not provide material to an employee that “is unlawful, threatening, abusive, defamatory, invasive of privacy, vulgar, obscene, profane or which may harass or cause distress or inconvenience to, or incite hatred of, any person”.

Officeworks employs thousands of young people. How do they determine what is “threatening, abusive, defamatory, vulgar, obscene, profane”?

Why was this young woman empowered to decide what material might “harass, cause distress or inconvenience to, or incite hatred” to “any person”?

This is not to defend this young woman – refusing to serve this Jewish customer was abhorrent. But let’s not forget that Officeworks has a policy that this woman believes empowers her to act in this abhorrent manner.

It’s a big enough ask expecting young employees to fairly determine what is incitement to violence when courts have offered no clue because prosecutors are loath to use the existing provisions that ban such actions.

At the other end of the spectrum, what are inexperienced employees to make of the legal free-for-all when it comes to subjective feelings such as “causing distress or inconvenience”?

Greens senator Mehreen Faruqi is suing Pauline Hanson under section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act claiming Hanson offended her. Faruqi has threatened action against this newspaper’s Johannes Leak, too, again claiming she was offended by a cartoon. Jewish groups are considering using 18C to prosecute words that they say offend and insult them.

Why are we outraged that a member of a generation raised in the shadow of the legal system that put a person’s feelings at the centre of laws to punish people for causing offence might think that their feelings trump all too?

We could have altered this offence trajectory. Instead, moves in 2017 to rein in the “offence and insult” part of section 18C went nowhere. Liberal MP Julian Leeser – who in recent days called for Officeworks’ chief executive to “hang his head in shame” – celebrated when feelings remained central to 18C. So did Jewish groups.

Politicians, poorly named human rights activists and Jewish groups still insist that we keep feelings at the centre of laws that can be used to punish people for causing offence. The young woman at the centre of the Officeworks brouhaha has simply moved the feelings bar a tad further down the line from actions that “offend” to those that make her “uncomfortable”. And why not, given that Officeworks policies do it too?

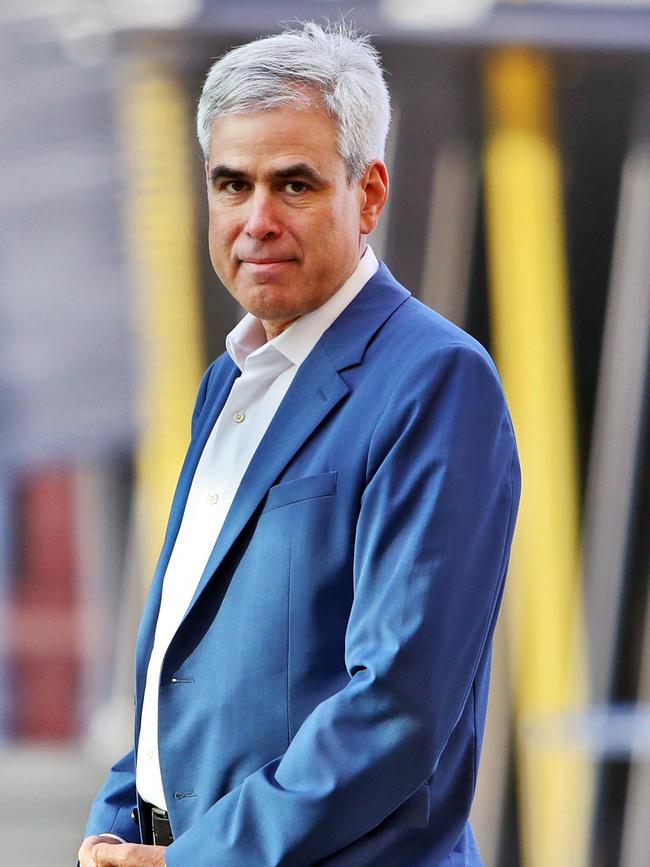

As a society, we can hardly pretend we didn’t see this coming. We have spent the past few decades turning a young generation into a fragile one. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and lawyer Greg Lukianoff wrote about this 10 years ago. Their essay in The Atlantic, The Coddling of the American Mind, laid out what was happening on American campuses. It’s little different in Australia.

Haidt and Lukianoff wrote about the frailty of university students raised by over-protective parents, where the “flight to safety” happened at school too when playgrounds became risk-free. These “social-media natives” cocooned in silos might be different, the authors said, “in how they go about sharing their moral judgments and supporting one another in moral campaigns and conflicts”. They need only look around to see a legal system where being offended provides an entry into a courtroom to make someone pay for hurting their feelings.

In September 2015, Haidt and Lukianoff warned that “attempts to shield students from words, ideas and people that might cause them emotional discomfort are bad for students”. They warned that it would be bad for workplaces, too, when students stepped into the real world, inevitably confronting what they were shielded from on campus.

It would be bad for democracy, too, the authors predicted with laser-sharp accuracy. “When the ideas, values, and speech of the other side are seen not just as wrong but as wilfully aggressive toward innocent victims, it is hard to imagine the kind of mutual respect, negotiation, and compromise that are needed to make politics a positive-sum game.”

Ten years on, we can remove “campus”, “college” and “university”, and “students” from The Coddling of the American Mind thesis and insert “workplace” and “employees”. We have reaped as we have sown.

To turn this around, Haidt and Lukianoff said it was critical to “minimise distorted thinking” so that those who felt discomfort “see the world more accurately”.

Maybe, then, sacking this Officeworks staffer is too easy – and also misguided. Maybe visiting the Melbourne Holocaust Museum is a better way to challenge this young woman’s distorted thinking. Her scheduled visit there (agreed after an earlier complaint) took place after the one caught on camera. If learning some history, gaining an insight into a deeply complex problem made her feel uncomfortable, all the better.

It’s certainly preferable to turning her into an unemployed martyr for the left.

This doesn’t get Officeworks or Wesfarmers off the hook. They need a new set of terms and conditions to make clear that just because something might cause distress – or discomfort, as this woman called it – that is no reason to refuse service.

Parents, politicians and universities have some important work to do, too. Complicit in raising a coddled generation, a good place to start is reminding kids, students, and adults that, as Haidt and Lukianoff wrote, “subjective feelings are not always a trustworthy guide; unrestrained, they can cause people to lash out at others who have done nothing wrong”.

Oh, and we should repeal section 18C.

If Officeworks sacked the young woman at the centre of last week’s storm for refusing to serve a Jewish man, that might satisfy some people – particularly the noisy ones on social media.