Indigenous voice to parliament remit keeps growing like Topsy

It will likely pass only if the Indigenous voice to parliament debate is censored. With legislation looming, the opposition must decide its position soon. If the Albanese government bluffs Peter Dutton’s opposition into the coward’s castle of a conscience vote, that is, not taking a formal position, Australia won’t get a debate.

The way voice campaigning has unfolded is alarming in several respects. First is the incoherence of the Yes case and its almost universal refusal to acknowledge that any argument against it is legitimate.

I don’t expect voice advocates to agree with arguments against their position, but they frequently suggest the only reasons anyone could oppose it are racism, cynical political exploitation, careerism or ignorance.

Thus we saw Noel Pearson’s ugly attack on senator Jacinta Price, accusing her of being recruited as a blackfella to punch down on other blacks. Presumably, that’s the future tone of the voice.

The changing justifications for the voice suggest its advocates are hiding its radicalism.

First, advocates claimed that to oppose the voice in principle before a clear proposal was put was premature and insulting to Aboriginal Australia, although of course advocates of a voice suffered no such admonishment.

Then the Prime Minister proposed his wording for a constitutional amendment. The opposition asked for the proposed structure and content of the new institution. Australians are being asked to vote for a radical new institution, what will it look like? Where’s the detail?

Shame, voice advocates replied. The detail is in the report by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton. Opposition politicians were flayed by ABC interviewers who cited detail from Calma-Langton.

OK, so is the Calma-Langton model the one the government will adopt? Can we come to grips with its structures and limitations?

No, no, no, the advocates switched quickly. The detail doesn’t matter. The detail will be decided by parliament. The detail, pace Calma-Langton, will take months to work out in consultation with Aboriginal groups after the referendum.

So how can opponents of the voice be dishonestly ignoring the Calma-Langton detail, yet the detail will be determined after the election? What were all those years of consultation about the voice for, if it all has to start again?

The Albanese government doesn’t need to include the structure of the voice in the wording of the referendum, but it does need to explain what version of the voice it plans to create.

The purposes and scope of the voice keep slip sliding around. First it was to be an institution for Aboriginal Australians to be consulted on legislation that affected them. It’s a vanishingly tiny proportion of legislation that affects only, or even primarily, Aboriginal people.

Most legislation affects all Australians, which means the voice will have a say on health, education, defence policy etc. That’s undemocratic because all other Australians get to vote only once, whereas those who can vote for the voice get two votes.

That is at the heart of why I think the voice is such a radical and bad idea. It rests on the notion that parliamentary democracy is not capable of representing certain minorities. This is an attack on parliamentary democracy in principle.

Everyone agrees that Aboriginal communities should always be consulted by government on matters that affect them. There’s no need at all to put that in the Constitution. One likely motive for constitutional change is a power grab by groups who think they can capture, or benefit from, a newly constitutionally privileged institution.

The voice is thus a weakening of parliamentary democracy and a rejection of the core principle of political liberalism, that all citizens are equal in civic status regardless of race, gender, religion, background etc.

As Malcolm Turnbull wrote in his memoir: “Our democracy is built on the foundations of all Australians having equal civic rights – all being able to vote for, stand for and serve in either of two chambers in our national parliament …

“A constitutionally enshrined additional representative assembly for which only Indigenous Australians could vote for or serve in is inconsistent with this fundamental principle.”

(Turnbull, perfectly conscientiously, later changed his mind on the voice, but I am convinced by this argument.)

The remit of the voice grows like Topsy. Now it’s a voice not just to parliament but to executive government, and now to cabinet as well. No one has the faintest idea what our ultra-activist High Court would do with all this.

However, two other elements of the voice, apart from the question of contradicting racial civic equality, are of growing concern.

One is the element of Cuban-style soft Stalinism about the demand for public unanimity on the voice. ABC and SBS news reports on the voice frequently contain naked editorial endorsement of the voice, as though there is no other legitimate position. It’s like the Chinese Communist Party denouncing ideological deviationism. It is truly shameful that the government plans to end the age-old practice of posting to Australian households a pamphlet containing the Yes and the No cases, will not fund either case but will provide government money for an education (re-education?) campaign, and will make only pro-Yes organisations tax deductible.

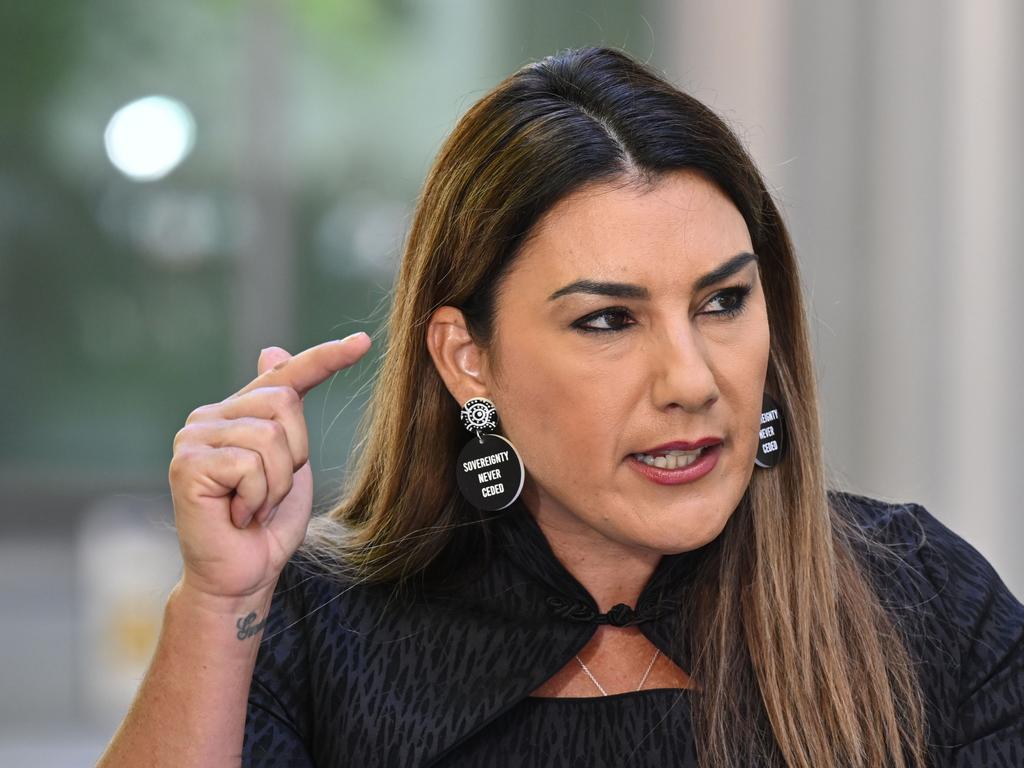

This is deeply undemocratic. The proponents of the voice are scared of having a real debate. Price and senator James McGrath typically had a small segment explaining why they will vote No censored by Facebook.

If Dutton’s opposition follows the beliefs of the overwhelming majority of Liberal voters and MPs and opposes the voice in principle and in practice, then ABC panels on the subject and the like will have to include opponents as well as supporters, and there is at least a chance of democratic debate.

Some Liberals argue that a conscience vote would allow them to avoid becoming the issue. This is just an excuse for raw cowardice. If the Liberal Party doesn’t have a view in principle about the most important, radical and ultimately unpredictable constitutional change proposed in modern Australia, it ought to just go out of business.

Strategic victory is seldom secured by tactical manoeuvres accompanying complete strategic surrender.

The other worry is that the voice will likely entrench the most destructive elements of identity politics into the heart of Australian life. Identity politics is killing Western societies.

It pits group against group. It is not about unity but constant grievance and performative pantomime, of grievance discovery, perpetual escalating apology, relentless identification of new villains and whipping up new hatreds.

The proponents of the voice say it’s only the first step to a treaty, presumably involving reparations, and truth-telling commissions, as though Australian history classes are currently anti-Aboriginal.

The voice would move Australian culture and politics several standard deviations to the left, permanently institutionalising the destructive dynamics of identity politics into every part of our national life.

This would be damaging for Australia. And, incidentally, disastrous for the Liberals.

The proposal for a constitutionally guaranteed advisory assembly to be chosen on grounds of ethnicity is so radical a departure from Australian constitutional practice, so bad an idea, such a bold repudiation of the liberal principle of equal citizenship for all, that if it were subject to searching debate and scrutiny it would probably fail.