On Wednesday, NSW Health Minister Brad Hazzard summoned up visions of a zombie apocalypse with masked undead queuing patiently outside the Brewongle Stand before entering the SCG in the hope of seeing Will Pucovski debut and the return of David Warner and eating their brains.

Citizens of Rookwood and other nearby suburbs were urged not to go to the third Test which starts on Thursday at the SCG as a cautionary move to stop the spread of what is known as the Berala cluster in Sydney’s west.

Never thought the Australia I lived in would forbid the dead from going to the cricket but that's where we are now. https://t.co/19Itt2ZcVO

— Jack the Insider (@JacktheInsider) January 5, 2021

‘Weekend at Bernies’ the gritty Oz re-boot

— Greg Burnett (@gregoburnetti) January 5, 2021

Hazzard explained yesterday that Rookwood residents had been excluded from ticket sales for the third Test which starts on Thursday.

“You must not attend this Test. Now, ticket sales have gone in a way that is aimed at ensuring that people from particular suburbs around Berala do not acquire tickets and do not come to the Test. That’s for your sake and for our community’s sake,” Hazzard said gravely.

“If you live in Auburn, Berala, Lidcombe North, Regents Park or Rookwood, we would love you at the Test in a non-COVID year, but we can’t.”

Of course, the joke (a very Sydney one) is that Rookwood is a necropolis, the largest cemetery in Australia and takes up an entire suburb. Rookwood’s only residents now dwell deeply in the past tense.

Amid the flurry of hysteria and wild accusations from other states with their armies of partisan barrackers, the NSW Government has successfully ring-fenced the pandemic avoiding widespread lockdowns and draconian restraints on movement and economic activity. Still, in these times a laugh, any laugh is worth having.

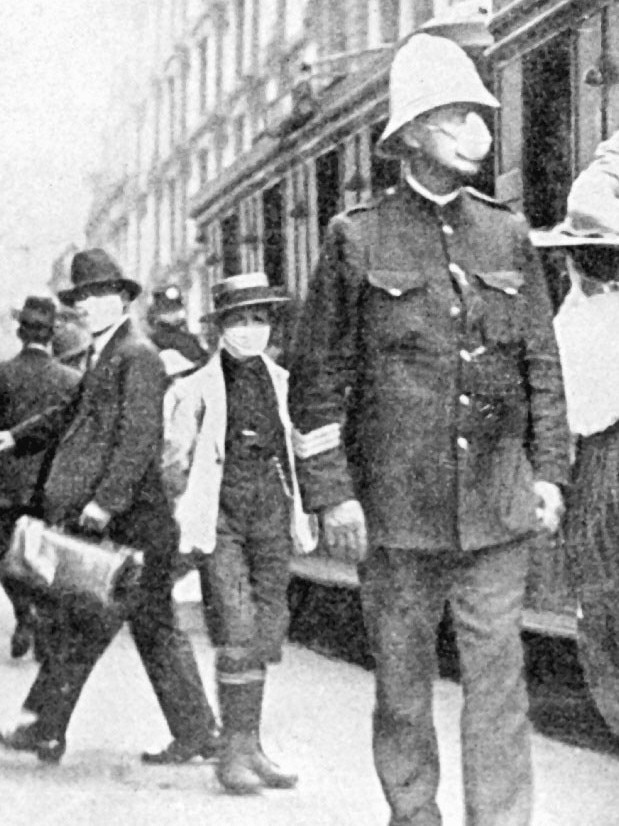

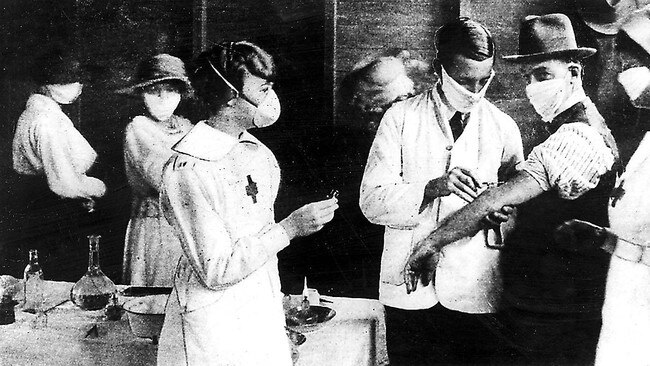

The really strange thing about the COVID-19 pandemic is it is an almost perfect reflection of Australia’s century-old response to the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19. Back then the federal government was roughly trampled out of the picture, the states lapsed into a hyper-parochial version of the Sheffield Shield and closed their borders while the people got roundly screwed.

Does any of that sound familiar?

In this lucky island continent stuck in the southern hemisphere, governments of the day could see the Spanish Influenza pandemic unfold and knew the virus was on its way. Its first wave had been especially virulent in Spain, rendering the King of Spain, Alfonso III, as crook as Rookwood thus giving the pandemic its name. Later, the second waves driven by the mutation of the virus, killed millions across the world.

In August 1918, with the world nearing the end of the Great War, Australia’s state and territory leaders met in Canberra and with the best of public policy intentions unanimously agreed that their federal counterparts would have jurisdictional carriage for quarantine and oversee the pandemic response through its newly formed Department of Health. Ink hit paper as state premiers signed off on the agreement. That great chorus of unity remained in place for precisely five months.

In January 1919 two demobbed servicemen presenting with symptoms were waved through Victoria and made their way to Sydney only to test positive to the dreaded lurgy.

The reaction was swift and angry. In New South Wales, where the pandemic had taken the fairly frequent visitations of bubonic plague off the front pages, Premier William Holman promptly closed the borders and within weeks, every state government with the exception of Victoria which had been sent to a sort of legal Coventry, did likewise.

Naturally, a great deal of movement across the borders should have been expected as Australian servicemen continued to find their way back to our shores only to find that if they were forced to disembark in a state they didn’t call home, they were stranded for the foreseeable.

For much of the time, Australia’s Prime Minister, Billy Hughes was out of the country, battling with US President, Woodrow Wilson and others who lazily wanted to hand over Germany’s Pacific colonies, including the northern part of Papua New Guinea, to Japan. Wilson who regarded Australia as an outpost and Hughes as an irritation, did not have the benefit of hindsight but anyone with even a passing understanding of 20th Century history would understand the looming geopolitical crisis that would have been headed Australia’s way.

While Hughes’ stubborn diplomacy forestalled that dangerous shambles, at least as far as PNG was concerned, the legal walls went up across Australia and roughly improvised camps sprang up on state borders which quickly became health and hygiene nightmares. Each state would eye these camps with alarm but spent much of the ensuing months trying to pretend they didn’t exist.

In Queensland, a camp just north of the Tweed had been established for two months before the Labor government led by TJ Ryan finally acquiesced and knocked up a women’s latrine.

South Australian Liberal Federation Premier Archibald Peake stuck his fingers in their ears and went nurny-nurny-nur-nur for much of the year. Those who dwelled in camps around Bordertown, Penola and Mount Gambier were not afforded such luxuries as running water or toilets, male or female.

Obviously these conditions are more appalling than the six hour bumper to bumper occasional splutter of internal combustion engines to cross the Murray River and into an abruptly locked Victorian border on New Year’s Eve but in a horses for courses way, it still resonates. I suppose the truly depressing thought is that our politics haven’t improved much in 100 years.

For all that, the Spanish Influenza had a relatively light touch in Australia. Quarantine was effective. Perhaps then as now, Australia received some benefit from geography. Being a great stonking island made for effective quarantine. Being a great stonking island in the southern hemisphere meant the first wave had come to Australia in the summer months, no doubt limiting the infectious life of the virus and saving lives.

The second wave hit harder in the late winter. By the end of it, between one third and one half of the nation’s five million population became infected with Spanish flu. Many presented with little or no symptoms. 15,000 died. Many Indigenous communities were all but wiped out with terrifying speed.

It might not quite be déjà vu all over again but the take home message of the Spanish Influenza pandemic in Australia more than 100 years ago is that Australians got through it, virtually despite the role of government. Social distancing and mask wearing were practised with or without government mandates. While public administration was chaotic, people came together, communities provided aid and comfort to the sick.

While there was panic and governments lapsed into hapless finger pointing, then as now, it was Australians who won the battle and ultimately the day.

I never thought an Australia I lived in would forbid the dead from going to the cricket but that’s where we are now.