Either Jim Chalmers has a poor memory or he wasn’t told the Australian Treasury operated a wellbeing framework from the late 1990s until it was ditched by Treasury secretary John Fraser in 2017.

Entitled Treasury Statement of the Wellbeing of the Australian People, it went by the awkward acronym TWOTAP. Five dimensions of wellbeing were considered: the set of opportunities available to people; the distribution of these opportunities; the sustainability of the opportunities; the overall level and allocation of risk borne by individuals and the community; and the complexity of choices.

I was shocked therefore to read the title of the Treasury’s latest offering: Measuring What Matters: Australia’s First Wellbeing Framework. Actually, that would be the second wellbeing framework, the first being abandoned because it was inaccurate, confusing and useless in terms of informing policy choices.

To be sure, the cake is cut in a slightly different way this time, but there are still five wellbeing themes that are supported by 12 dimensions and 50 key indicators.

While the platitude that “what is measured is managed” may seem to justify the Treasury’s reworked approach, the reality is that such a large number of measures actually means nothing is achieved through this laborious and often outdated exercise. The quality of the report is a blight on the reputation of this central agency.

We had been given a taste of this new wellbeing framework in the federal Treasurer’s first budget last October. He had already pledged to introduce this approach to budget management, copying New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern.

After I spent several hours in the lockup, the chapter in the budget papers, also entitled Measuring What Matters, at least gave me a few laughs. The chapter reviewed the OECD Framework for Measuring Wellbeing and Progress, a bad starting point given the diminishing reputation of that organisation. I also learned that Canada, Britain, Germany, Iceland and Italy as well as New Zealand have all had introduced national wellbeing frameworks. Wales and Scotland have their own versions.

Talking of numbers, Italy has 153 indicators of wellbeing, while Britain has a meagre 38. Our cousins over the ditch have 22 policy areas and 103 indicators.

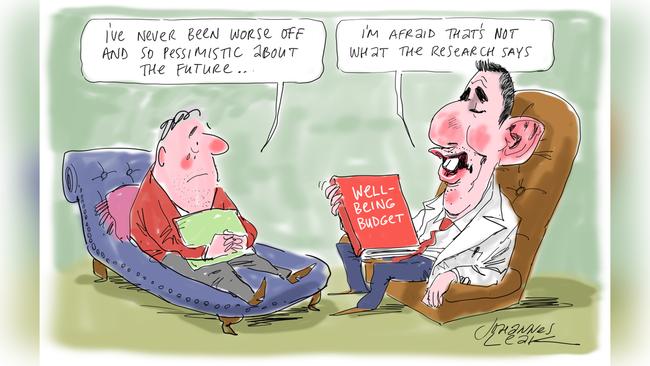

According to the budget papers, “New Zealand is the only country that requires all new policy proposals to specify their contribution to wellbeing and be evaluated on this basis.” Sadly, for that country, this has not led to good policy or higher wellbeing for the population, with unaffordable housing and sky-high mortgage rates core features of the current problematic environment for the population.

I have always used the rule that if something looks wrong, it almost always is. So, the claim in last year’s budget papers that housing affordability in Australia had been “stable and higher than the OECD average from 2004 to 2020” looked highly dubious. This mistake has been carried forward to last week’s report.

Using out-of-date figures from 2020, it is now pointed out that mortgage holders were spending less of their take-home pay than two decades ago. But given the dozen interest rate rises since then, this observation is of only passing (and unhelpful) interest. The reality is that the proportion of homeowners suffering mortgage stress is high and rising. Rent as a proportion of incomes has also been rising steeply.

Obviously, these are core elements of people’s wellbeing. To use figures from three years ago is inexcusable; they are easy to update. This naturally leads to a discussion of what really matters to people rather than the many ephemeral issues raised in the report. Note here that the Treasury was allocated an additional $157m to conduct the wellbeing analysis, money that could have improved the wellbeing of disadvantaged citizens directly.

If you are struggling to pay the mortgage or rent and utility bills as well as feed the family, do you really care about the proportion of female federal parliamentarians and the fact it has been rising? Or that the proportion of waste recovered for reuse, recycling or energy has increased? Or that the proportion of land dedicated to conservation of nature has risen?

The bottom line is that the report is actually insulting to most ordinary folk going about their daily life. It gives a completely undeserved impression that your wellbeing is essentially in the hands of the government and, given the right policy settings informed by the wellbeing framework, you will be better off.

This is notwithstanding the awkward finding in the report that people’s trust in the federal government has fallen significantly in recent years.

And just in case you need a laugh, consider this quote from the report: “The framework’s usefulness will extend beyond government. It has been specifically designed to be drawn upon by business, academia, and the community to support their efforts to create better lives for all Australians.”

The report is a complete mishmash of data pulled from various sources, including some very limited surveys. A lot of it is outdated and tells us nothing about what is happening now.

While Chalmers had to accept the report’s deficiencies, he maintains it is a work in progress and will be improved. The only saving grace is the report doesn’t try to add up the measures or reach some highly questionable global measure of wellbeing. Thank god for small mercies.

The real risk is that Chalmers actually takes the report seriously, feeding into his bizarre quest to reinvent markets and to establish a new form of values-based capitalism, whatever that means.

No doubt he will be able to find a rationale for promoting supply-side resilience, which is just another term for industry protection, or offer more subsidies for overseas renewable energy companies, because these measures will supposedly add to our wellbeing.

The wisest choice he could make would be to abandon the exercise before it got worse. Treasury should be focusing on what it does best, not undertaking empire-building expeditions into areas in which it has no expertise at all.

No sensible economist thinks gross domestic product (or, more precisely, GDP per capita) is the only thing that matters. It’s why a range of indicators is used to build up a picture of how the economy is travelling and how this is affecting people. And where there is high correlation between the standard economic measures and people’s wellbeing, there is really no need to go beyond the stable of traditional indicators.

And don’t forget the most important point of all: my wellbeing is not the same as your wellbeing. Reports such as this simply cannot deal with this distinction.