Fundamental issues such as the giant structural deficit we’ve built into our budget, our shocking productivity performance, the collapse of an economic and population growth ethos that is essential to our security, our dreadful failure to provide any meaningful defence capabilities are all neglected.

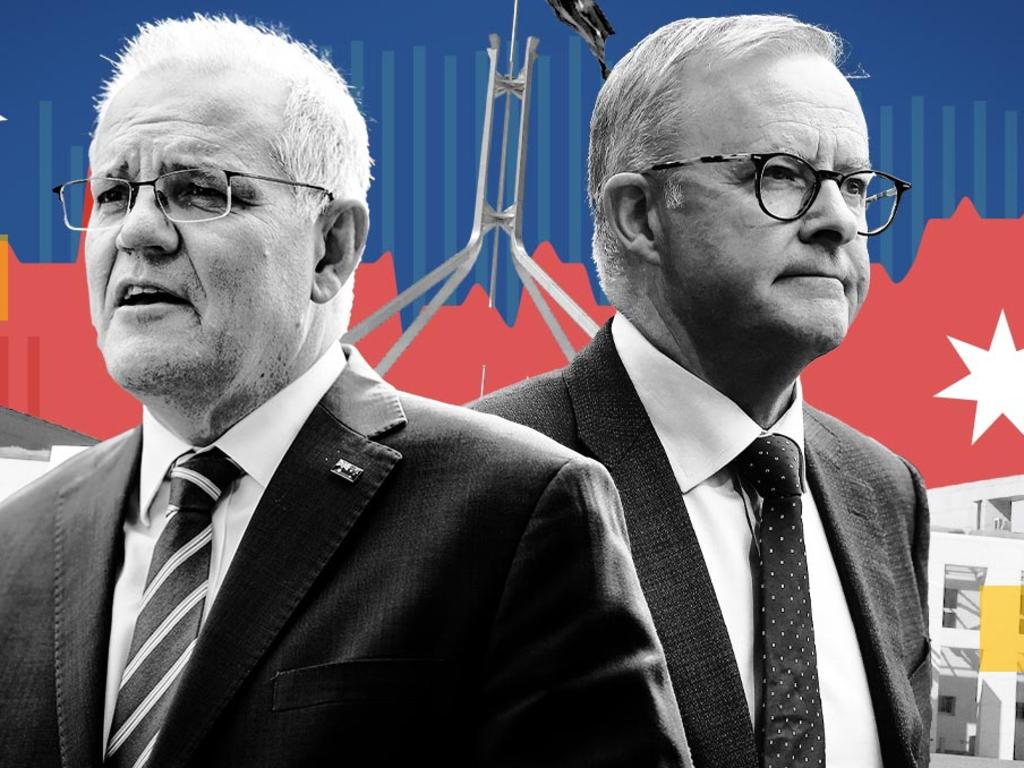

Politics is reduced to three considerations – who can I give targeted money to in return for votes; who can be shamed, abused and demonised for offences against identity politics etc; and did either leader say something stupid or that could be portrayed as stupid? Most advertising will be directed at convincing us that two perfectly decent men – Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese –are dunderheads, ideologues or bigots.

The dynamics are similar across the West. Consider three aspects: social media, the efforts of our enemies, and the fatigue if not exhaustion of the Westminster system.

Jonathan Haidt in a fascinating piece in The Atlantic, Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid, offers a precise cause of our political crisis. This crisis became apparent around 2015, with the “Great Awokening” on the Democratic left, and Donald Trump’s ugly populism on the Republican right.

A good democracy depends on social capital – that is, networks of trust – strong institutions and shared stories. Social media attacks all three. Haidt identifies the moment a decade ago when the retweet on Twitter and the “like” function on Facebook came into play as decisive. Social media had been a way to connect. After that it became a performance.

Gaining thousands of retweets and likes created celebrities, influencers and bullies. The social media algorithms favoured not just your existing biases but were specifically set to maximise likes and retweets. The quality that most attracted likes and retweets was anger, especially anger at some out-group or identifiable enemy. So the whole eco-system designed itself to identify, amplify and actually create anger.

This anger produced immense power. It also was self-reinforcing in strengthening extremists and marginalising moderates. Moderates were frightened away by abuse. Moderate and nuanced comments did not in any event excite a big response. Both left and right went mad. The left demonised anyone it disagreed with, or indeed anyone who merely transgressed, often enough unintentionally, codes of verbal conformity. People’s arguments were not addressed. Instead they were labelled racist, sexist, homophobe, transphobe or some other term that implied they were morally corrupt and wicked people driven by hateful prejudices.

It was easy to run Twitter and Facebook campaigns against people and get them sacked or sometimes hound them into breakdown or even suicide. Universities and other cultural institutions responded with rank cowardice, seldom defending the innocent.

We often think this polarisation divides people into left and right but, as Haidt points out, the extremists spend an enormous amount of their time policing dissent, or policing what they see as insufficient fervour, on their own side.

The right was just as bad. Anyone who didn’t embrace whatever kooky conspiracy theory and latest one minute to midnight disaster scenario doing the rounds was not just mistaken but was a “traitor”. Thus right-wing protesters demanded “death to Mike Pence” because Pence, surely the most conservative US vice-president in many decades, would not join Trump’s ludicrous attempt to ignore or reverse his defeat in the election. Similarly countless election officials, mostly Republicans, in states that voted for Joe Biden have been subject to death threats.

So a great deal of the discourse on left and right in democratic societies now has nothing to do with reality, or at least presents a hugely distorted reality.

If that’s not all cheerful enough, the situation is about to get much worse, Haidt reports. Artificial intelligence can now produce an almost limitless supply of false news, and plausible false opinion based on things that aren’t true, on any issue you program and with any tone you want. AI will get better and better at this.

That’s bad enough and will be exploited by extremists within our societies. But it will also be weaponised by Russia and China and other hostile international actors. If people on social media see something that fits much of what they already believe to be true, but that is not true, they are more inclined to believe that than to go to the trouble of checking facts authoritatively. So Chinese, Russian and other external actors can have a big and damaging influence on our social media – watch for nuclear-powered submarines to be demonised in Australia.

I can’t tell you how often I run across this in casual life. Years ago I was talking to a young publishing executive about a possible book. She asked me in all seriousness if I was a CIA agent.

I assured her this was not so and she knowingly, shrewdly commented that of course if it were true I wouldn’t be able to tell her. That’s an extreme example, but there are many others.

This assault on trust, shared stories and facts, and on institutions, is evident now in our politics. The idea of the Westminster system is that a party or coalition presents a coherent program, wins support and is elected, implements the program and is judged on the results. Our two main parties have grave limitations but mostly live in the real world. They now command less than 70 per cent voter support between them.

The miscellany of minor parties and independents is often utterly detached from reality – as in the Greens this week declaring China is no threat to Australia – and none of them even pretends to present a coherent program for government.

But the major parties are conniving in their own demise. The Victorian Labor Party has had its normal operations suspended for two years, with another year to go, so that all preselections have been determined by a professional cadre at the top. In NSW the Prime Minister determined 12 federal preselections, with not a speck of internal democracy. Both parties’ leaderships are treating their rank-and-file membership with contempt, behaving in a way that is intensely undemocratic.

Unless they were seeking paid employment in politics, why would anyone bother being a member of the Victorian Labor Party or the NSW Liberal Party?

Social media is hurting our democracy, our enemies take huge advantage of this and our leaders are undermining their own parties as institutions.

Good luck with all that.

This low-rent election campaign we’re going through is fascinating because it’s getting closer and more unpredictable. But it’s a spectacular illustration of the decline in our political culture.