Mental health experts argue that the full scale of the damage caused by coronavirus, particularly among young people, is yet to be fully appreciated. While we in Australia are not dealing with the tragedy and chaos of places such as the UK and US, the chronic uncertainty created by the pandemic inevitably leads to an undertow of stress.

Professor Ian Hickie of the Brain and Mind Centre at Sydney University has described the mental health impact as a “shadow pandemic” that is largely invisible, because “unlike the virus, you don’t get sick in seven to 14 days. The factors accumulate”.

While those of us who are more established in our professional and personal lives can fall back on familiar routines, or the comfort of partners for support, young people can find themselves alone and with little to keep them busy during periods of reduced activity. And the challenge we face is that the pandemic, and the social distancing measures required to deal with it, may be compounding some unhealthy patterns that were already trending upwards well before 2020.

In 2017, social psychologist Jean Twenge published a book called iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy — and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood and showed that American teens born after 1995 engage in less socialising than prior generations. In the US, young adults born after 1995 drink alcohol less, go out less, socialise less, are less motivated to get their driver’s licences, work less, date less and even have sex less often than previous generations. Similar patterns have been observed in Australia.

The implications are a double-edged sword. While on the one hand, it is no doubt a positive development that today’s teens and young adults are not engaging in as many risky behaviours that lead to unwanted pregnancies and harmful drug use as previous generations, many other experiences, such as getting a job and learning to drive, are an essential part of growing up. They are also important for establishing independence and a stable personal identity.

Twenge’s book identified these changes in behaviour as beginning around the same time the smartphone became ubiquitous, hence the title, “iGen”. While it hasn’t been proven definitively, psychologists suspect young people are either eschewing social behaviours intentionally due to social anxiety, or avoiding them indirectly, due to being distracted and preoccupied by their screens.

In 2019, Twenge published a follow-up study that looked at loneliness in young adults and found that since 2011 the amount of time young people spend on socialising face to face had decreased, while time spent socialising in digital environments had increased. This trend correlated with sharp increases in loneliness, with young people spending the most time on social media reporting the highest levels.

And loneliness is one of the most widespread outcomes of the pandemic. The Australian National University’s Social Research Centre has shown that while Australians, and in particular residents of Victoria, have experienced high levels of distress during the second wave, Australians, “including Victorians”, were being bounced back to pre-COVID levels by November last year, except for those reporting high levels of loneliness. And the age group experiencing the highest levels of loneliness during the pandemic is 18-24-year-olds.

Thankfully, it’s not all doom and gloom. Some early data suggests mental health impacts on teenagers have not been as dire as first predicted. Suicide statistics were lower in 2020 than in 2019, in Victoria and in NSW, surprising some forecasters. One reason may be that JobKeeper payments and the doubling of unemployment benefits buffered the impact of the economic downturn and job losses for many. Another reason may be that there is a sense that “we are all in this together” and that the hardship is shared collectively, as opposed to a burden felt by an individual alone.

But we need to be cautious not to over-interpret the data. In Japan, during its first wave of coronavirus, suicide rates decreased by 14 per cent. But by the second wave monthly suicide rates increased overall by 16 per cent, with a 37 per cent increase for women and a 49 per cent increase among children.

And Japan, like Australia, has not had a disastrous death toll like the UK and US. Nor has it had an economic downturn as severe as in other countries. The ways in which the pandemic are impacting our collective mental health are complex and unpredictable.

One thing we do know and understand is that early intervention by mental health professionals can make a huge difference in the lives of young people who find themselves in trouble. So we need to make sure that accessing mental healthcare treatment is as easy as logging into an app from a bedroom and as easy as picking up the phone to text a friend.

As a society, we have been successful in coming together as a collective to defeat multiple outbreaks of coronavirus. Our next challenge will be coming together to help our young people rebound.

Claire Lehmann is editor-in-chief of the Quillette platform for free thought.

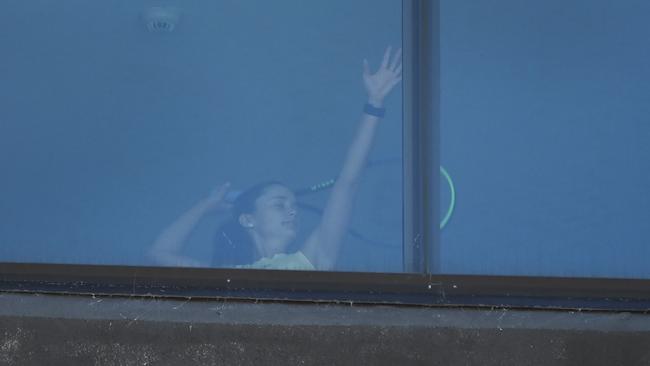

The picture of professional tennis players trapped in cramped accommodation hitting balls against hotel walls recently brought home to me what a strange and exhausting time we all live in. When the pandemic started, most of us knew it was going to be a marathon, not a sprint, but with the advent of a mutant variant that is 50 per cent more transmissible, and with a vaccine rollout still weeks or months away, the “new normal” remains taxing even for the most resilient among us.