Shorten and Turnbull offer lessons for Albanese and Morrison

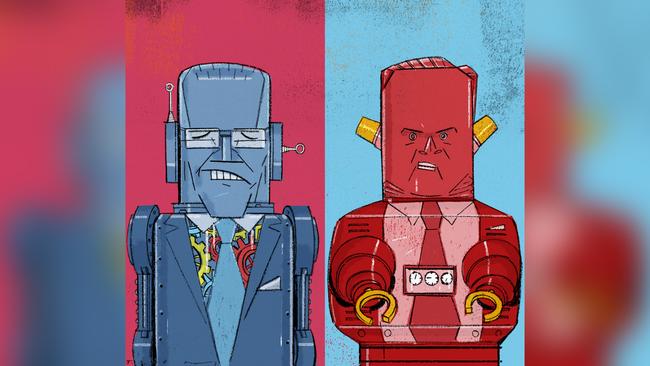

Disunity is rightly regarded as death in politics, so it must follow that unity is key to victory. Well, yes and no. It is possible to be so obsessed by it, so fearful of criticism of any sort, that passions are smothered and politicians turned into robots or parrots too frightened to deviate from the script provided by central command.

There is a difference between a legitimate questioning of, or discussion about, policies and positions the leadership has taken, between a healthy, essential debate about direction, and behaviour that amounts to outright sabotage of the leader and the party’s electoral prospects. People generally are smart enough to recognise that difference.

Sabotage is what happened for three years under Malcolm Turnbull. It ended up destroying his prime ministership and, as we are seeing (and will continue to see), leaving scabs that will never heal.

Smothering is what happened on the Labor side. Bill Shorten’s singular achievement was keeping Labor united, but in the end it contributed to his downfall. After the bloody Rudd-Gillard-Rudd wars, the last thing Labor MPs wanted was a fight. About anything. The acquiescence, the one world view, from the very beginning of Shorten’s tenure, then for almost six years thereafter, ultimately helped cost them two elections.

A bit of resistance here or there might have pulled Shorten back from the disastrous course he had undertaken, the one that rendered Labor incapable of defeating a party that had three prime ministers in three years.

He made himself the issue and he did it by adopting the wrong policies. An unpopular leader saddled with unpopular prescriptions: if there is a deadlier combination to put to voters, it has yet to be discovered. The Liberal Party was determined this time not to replicate the mistakes of 2016 — regardless of who led it into the election. It had committed months in advance to clearly defining the choices and to running a short, strongly negative campaign highlighting the risks Shorten’s Labor posed to the economy.

Labor had also committed itself to an approach well in advance; then, when circumstances changed, it failed to change to accommodate them. At times it looked as if it thought it was still fighting Turnbull, not Scott Morrison.

Every Labor MP climbed aboard the Shorten caravan, which eventually turned into a train wreck.

A few Labor MPs have decided they are not going to do that again. Joel Fitzgibbon for one; Fitzgibbon suffered a 9.5 per cent two-party preferred swing and One Nation scored a primary vote of 21.6 per cent in his previously safe seat of Hunter.

Fitzgibbon has argued the government’s entire package should be waved through so Labor can move on to other things.

Sensibly, Anthony Albanese has neither complained about his MPs speaking out nor sought to discipline them. He needs to maintain a degree of tolerance.

The Opposition Leader and his Treasury spokesman, Jim Chalmers, have unveiled a holding position — or a half-pregnancy — which they argue takes account of economic and political realities.

They have suggested that the government should bring forward the second stage of the $158 billion tax cut package by three years, along with infrastructure spending, to give an immediate boost to the slowing economy. Labor argues stage three should be split from the package and is — so far — withholding support for that part of it.

As always, it will be about the numbers and it appears the government will have them, with the support of the crossbenchers, for the package to pass in full.

The question Labor then has to confront is whether it wants to fight this issue all the way to the next election and beyond, by allowing itself to be cast as the party that voted against income tax cuts. That would be stupid and futile, and would risk a repeat of 2019.

Dealing with tax as cleanly as possible next week would leave Labor free to focus on other things, to force the government to talk about something else, perhaps even to shift the media spotlight on to whatever the government is or isn’t doing. Or even what happened last August, which remains highly relevant.

The Prime Minister has cobbled together a post-election reform agenda that included workplace reforms (commendable, if belated) and eliminating red tape (laughable).

It was regrettable that, at the same event, he passed on the opportunity to comment on the dumping of Israel Folau’s page by GoFundMe — then bolted from his press conference.

What Folau has said is offensive to many people, but if people agree with him and want to donate to his legal defence, that is up to them. He is entitled to ask for money and people are entitled to give it to him. As someone who campaigned so hard for the protection of religious freedoms during the same-sex marriage plebiscite, that was the least Morrison could have said when he was asked, not offer some lame excuse about not wanting to give the issue more oxygen.

It was an important story whether he wanted it to be or not. He should have said something.

It was similar to his early dismissal of concerns about police raids on News Corp journalist Annika Smethurst and the ABC. Another important story.

Only a very brave — or foolhardy — prime minister would ignore the messages delivered yesterday at the National Press Club by News Corp Australasia executive chairman Michael Miller, ABC managing director David Anderson and Nine’s chief executive Hugh Marks on the urgent need for government action to protect press freedoms, journalists and whistleblowers.

Morrison’s occasional dismissive approach is reflective of his mindset when he wants to focus on his own issues or objectives. That can be a strength, as shown by his discipline and single-mindedness during the election campaign. But it also can be a weakness. It means he misses opportunities to insert himself into vital public debates or takes too long to respond to problems.

Inside the government, Morrison also has a reputation for not reacting well to criticism or taking kindly to those who disagree with him. He needs to work on that, too.