The Virgin Australia collapse, however, illustrates that even wartime and pandemic powers of government must be used sparingly and be carefully scrutinised. Two particular Virgin-related issues should be considered. The first is whether governments should invest in or, more accurately, bail out private sector companies. The second is the extent to which governments should second-guess private investments by foreigners.

As to the first, we know that the special pleading starts whenever a large employer such as Virgin Australia is on the cusp of collapse. Forget the lessons of history that government bailouts end badly. This is different and in the national interest, we are told. Please save us by giving money.

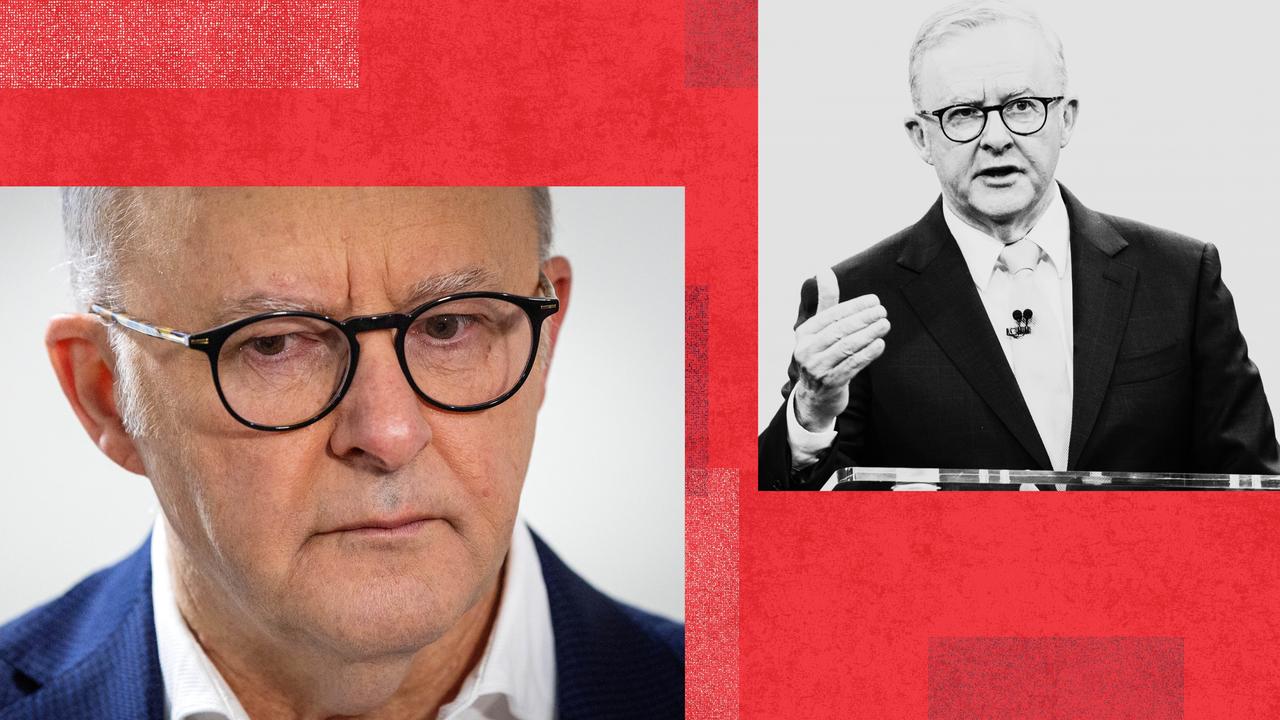

Labor, under Anthony Albanese, was keen to cave in, meaning that taxpayers would have ended up shovelling buckets of money into an inefficient business. At least the ALP might have pocketed some financial benefits out of the carcass via union money channelled into election campaigns.

Because only ideologues can be pure, it’s true that sometimes governments must grit their teeth and nationalise industries or parts of them. The semi-nationalisation of Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds in the UK in the face of a banking disaster was pragmatic and necessary. But it is a calculation that requires great care. When it comes to Virgin Australia, the Morrison government has taken a principled and pragmatic path. It has provided economy-wide stimulus such as JobKeeper (which Virgin can claim) and sector-wide concessions to the airline industry as a whole but is refusing to give it specific relief.

Fortunately for taxpayers, the government will not pick winners. It will particularly not pick losers.

And Virgin is, and has been for some time, a loser. Unlike Qantas, which has been managed prudently, Virgin was screwed by poor management and divided owners long before the catalyst for its collapse, COVID-19. Virgin turned a profit only once in the past 10 years. Its share price has fallen from $2.19 in February 2007 to $0.086 before being suspended from trading a week ago. It has an unsustainable $6.8bn mountain of debt that only an administration can reduce or reorganise.

The Opposition Leader is out of his depth if he doesn’t understand that if Virgin were a good business with a decent future, then its sophisticated and well-heeled shareholders — Etihad, Singapore Airlines and Richard Branson — would have bailed it out before Deloitte’s appointment as administrator last week. That these world-class aviation investors declined to throw good money after bad is all you need to know when asked if the Australian taxpayer should tip in.

The Morrison government has done something that Labor, under Albanese, could not have done: saved taxpayers from an expensive failure while allowing the market to supply the solution that the market can afford.

Private equity players and other aviation investors are circling because they believe Virgin, or the key parts of it, will be sold and the airline will rise again, although in very different form. It will never be the same again, and that is as it should be.

In coming weeks, Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg will need to stand firm if prospective buyers, or Virgin administrators, claim the airline needs taxpayer help to get a sale over the line.

Now to the second and related issue. Some observers have suggested the two big Chinese investors in Virgin, Nanshan and HNA, were prepared to put more money in to rescue and take control. When should a government use foreign investment controls to stop foreign rescues, or indeed any acquisition, of an Australian business?

The question becomes especially acute since the Morrison government, concerned about opportunistic takeovers of distressed companies, has lowered to zero the threshold for Foreign Investment Review Board approval of foreign acquisitions. For six months, all foreign acquisitions must be approved by the Treasurer on the advice of FIRB.

Since the day the First Fleet arrived, Australia has been built on foreign investment and has always been a net importer of capital. Without lashings of foreign money, the country would look nothing like the modern, advanced economy it is. Given that we can’t supply all our own capital needs, Australia must continue to encourage and welcome foreign investment, within sensible limits.

Investments by foreign governments, and their state-owned enterprises, are different in kind from purely commercial foreign investments. Foreign governments will often invest for strategic, not commercial, reasons. They can take losses in pursuit of geopolitical advantage. If it is true that the government has knocked back a Nanshan or HNA rescue of Virgin because it doesn’t want China owning a big chunk of Australia’s aviation industry, it deserves more applause for taking the principled road.

Again, however, great care is needed. Foreign investment controls used on the grounds of compelling national strategic interests must not be twisted into some kind of de facto poison pill takeover defence for incumbent Australian boards and management.

It’s not unknown for existing boards or management to spin the most desperate, occasionally outrageous, yarns to justify FIRB advising the Treasurer to interfere with standard corporate transactions to entrench their control.

It’s amazing how cunning political lobbyists can find national interest arguments hiding inside plain vanilla investments if it helps clients keep their comfy board seats or corner executive offices. But this is an abuse of foreign investment controls. FIRB is not there to protect company founders or their hand-picked boards and management from their shareholders, or from the normal operation of traditional takeover rules. Nor should it be the arbiter of the price at which shareholders should be allowed to sell their shares to bidders.

FIRB has no better track record of picking winners than any other arm of government.

The Treasurer, who oversees FIRB, will surely be vigilant in ensuring it confines itself to matters of national interest and doesn’t stray into matters of corporate control. The pandemic may justify additional scrutiny, in the short term, of foreign acquisitions by foreign governments and their SOEs, but it should leave ordinary commercial transactions by foreigners alone. After all, we will need a lot of foreign investment when we get to the other side of this pandemic.

Today’s crisis raises important questions about the role of governments in commerce and industry. Only an anarchist, or a fool, would deny that governments should play an exceptional role in exceptional circumstances. Wars and pandemics are the pre-eminent examples of governments needing, and deserving, powers and interventions that one could never justify in more normal times.