With the courts already issuing 30 preliminary injunctions and temporary restraining orders, Elon Musk, whose Department of Government Efficiency has been their primary target, has denounced what he claims is the “TYRANNY of the JUDICIARY”, while lambasting federal judges as “corrupt”, “radical” and “evil”.

Not to be outdone, Trump this week called Judge James E. Boasberg, who sought to pause the deportation to El Salvador of more than 200 alleged members of a Venezuelan gang, a “Radical Left Lunatic”, and urged his impeachment – prompting a rare rebuke from Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts.

To make things worse, despite the White House’s denials, there are compelling reasons to believe Judge Boasberg’s order to pause the deportations was simply ignored. Given that yet more injunctions and restraining orders are certain to be issued in the weeks ahead, the stage seems set for a major confrontation between the presidency and the courts.

Quite how the clash would play itself out is hard to tell. The federal judiciary has often been referred to as “the least dangerous branch”, following from Alexander Hamilton’s assertion that the Supreme Court “is possessed of neither force nor will, but merely judgment”. The judiciary, wrote Hamilton, has “neither purse nor sword” and hence “must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments”.

But the contemporary reality is more complicated. It is settled law that no one has the right to ignore a court ruling, regardless of their view of the ruling’s correctness. As the Supreme Court stated in 1911: “If a party can make himself a judge of the validity of orders which have been issued, and by his own act of disobedience set them aside, then are the courts impotent, and what the constitution now fittingly calls ‘the judicial power of the United States’ would be a mere mockery.”

It follows that the federal courts both “possess inherent authority to initiate contempt proceedings for disobedience to their orders” and “cannot be at the mercy of another branch in deciding whether such proceedings should be initiated”. As a result, courts can impose penalties that include arrest and imprisonment for “civil contempt” – that is, for disobeying their instructions.

Normally, those penalties would be enforced by the US Marshals Service, which sits within the executive branch and is potentially subject to direction from the attorney-general. However, should the Marshals Service refuse to carry out an arrest, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure allow the courts to assign that task to any “person specially appointed for the purpose”, including state and local police forces, which are not under the attorney-general’s control.

Additionally and importantly, it has, ever since the Supreme Court’s decision in Ex parte Grossman (1925), been settled law that while the president can pardon criminal contempts (which involves disrupting or impeding proceedings that are under way, for example, by improperly refusing to testify), civil contempts – which occur once a decision has been handed down – are not within the scope of the president’s pardon power.

The president himself may be protected by presidential immunity; but anyone else who breaches, or assists in breaching, a court order inevitably incurs very serious risks. Nor does the mere fact of having been instructed by the executive to breach the order provide any protection from prosecution and conviction.

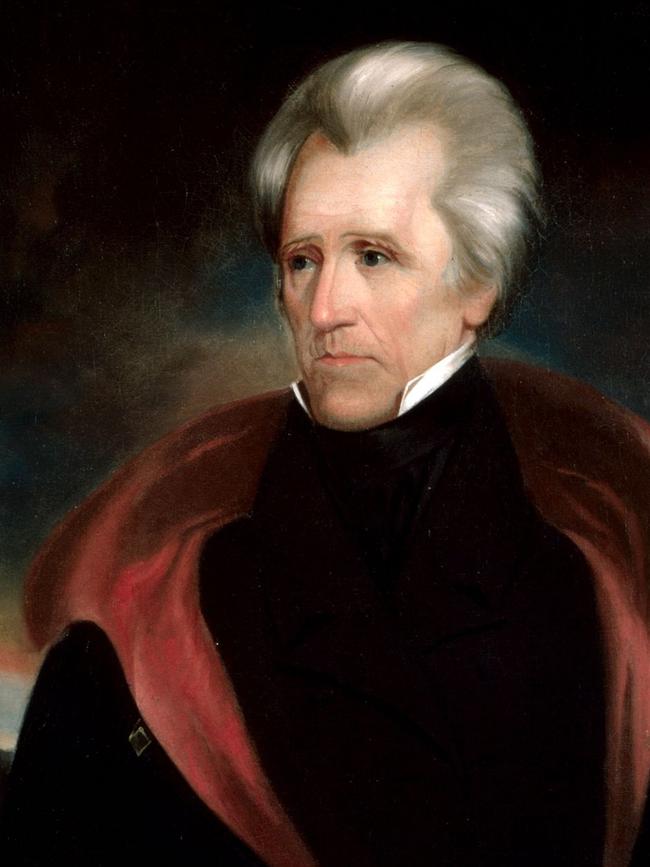

Whether it will come to that remains to be seen. But the similarities between Trump and Andrew Jackson, whom he idolises, are telling of what may lie ahead.

Jackson notoriously set a precedent in 1832 by ignoring a Supreme Court order that upheld the rights of Cherokee Native Americans. “John Marshall,” Jackson allegedly said, referring to the then chief justice, “has made his decision; now let him enforce it” – which, in the circumstances of the time, Marshall was unable to do.

Jackson was the first president to claim he was invested with a “mandate from the people”: a mandate that, by its very nature, overrode any constitutional limitations. Unlike his predecessors, he did not see the presidency as a conventional balancing institution, hemmed in by congress and the courts; it was, he maintained, the direct embodiment and highest expression of the popular will.

Convinced that the president was the guardian of the national interest against “the predatory portion of the community” – that is, the elite, who he described as a “leech” on the body of the people – and that the fate of liberty was at stake, Jackson claimed he was fully entitled to sweep aside those who “from cupidity, from corruption, from disappointed ambition and inordinate thirst for power” threatened the popular will, including the courts.

This was, in other words, an all-or-nothing battle against a uniquely cunning and dangerous adversary; and reminding his countrymen that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty”, Jackson assured them that “whatever disguise the actors may assume”, those who sought to “bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes” could not and would not be allowed to triumph.

That set of beliefs – in an overriding popular mandate that impels a fight to the death against “corruption” – is at the very heart of Trumpism; it is, indeed, its most enduring feature.

Thus, stating his mission as being to defend ordinary Americans from a “global power structure”, Trump has described the situation the United States faces as “a crossroads in the history of our civilisation that will determine whether or not we the people reclaim control over our government”.

“This is,” he claims, “a struggle for the survival of our nation” in which “for them (that is, the adversaries) it’s a war, and for them nothing at all is out of bounds”.

Little wonder then that he has rebutted the claim that his administration is cavalierly flouting court orders by saying that “he who saves his country does not violate any laws” – a phrase, commonly attributed to Napoleon, that was used by Kaiser Wilhelm II to justify Germany’s invasion of Belgium in August 1914.

Of course, it may be that the administration will back down. The almost farcical lengths to which it has gone in trying to explain its failure to implement Judge Boasberg’s injunction, and the somewhat more cautious wording of its most recent executive orders, suggests a growing awareness of the possible dangers.

What is clear, however, is that it passionately believes the country is in the midst of a potentially fatal emergency, justifying whatever action it considers necessary. If Donald Trump continues to act on that basis, Americans may be about to discover whether their republic, which was the modern world’s first successful experiment with mass democracy, can and will remain blessed by “a government of laws, not of men”.

Since January 20, when Donald Trump was inaugurated, 142 cases have been brought against the new administration – and additional cases are being launched every day.