Nothing in the Irish Troubles, through the late 1960s to the late ’90s, came close to the savagery of Hamas. The Irish Republican Army, whose bombing campaigns in England are one of my earliest memories, were not pathologically anti-British (well, perhaps some in the IRA were, but few). They were careful about the people they killed. The only American to die by the terrorism of either side was an unlucky shopper at Harrods (killed by an IRA bomb in 1983).

The bloodlust of Hamas has no equivalent. Its terrorists are driven not by Jewish behaviour but by Jewish existence. While Israel will attempt to limit civilian casualties, Hamas will maximise them. Killing Jews is its raison d’etre. Killing Brits, for the IRA, was a tactic, not a cause. The history of Irish republicanism contains some significant Protestants leaders; there are no Jews in Hamas.

Despite the stark differences in intensity and hatred between these conflicts, the path to peace in Israel often is said to pass through Belfast. This is a tempting road map. I played a small part in drafting it. At the turn of the century I worked with assorted political parties and officials to build connection across the sectarian divide. I travelled on buses taking previously warring Northern Ireland politicians to visit sites of US political co-operation – like congress! I drank Guinness in Irish-American pubs and sang rebel songs unionists-loyalists knew as well as their nationalist-republican opponents, whose forebears had written them.

Israel-Palestine doesn’t have Guinness as a lubricant of peaceful coexistence. But it lacks much more than that. Extrapolating from the Irish peace process is a fool’s errand.

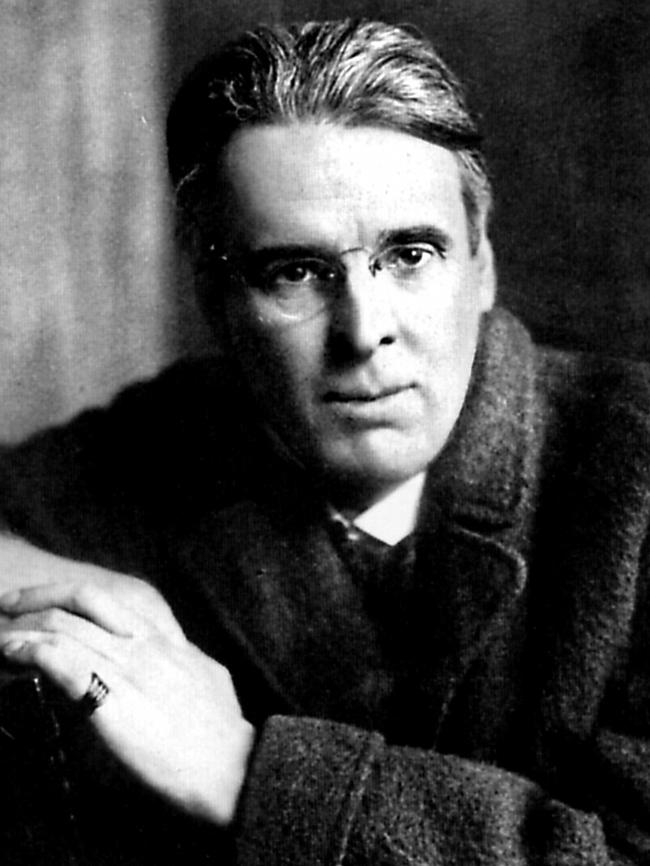

At its simplest, peace in Northern Ireland was achieved by hollowing out the political middle ground and empowering the extremes. As WB Yeats bemoaned in The Second Coming (1919), the most quoted Irish poem written: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” After 1998, centrists were cast aside, first by British, Irish and American negotiators, then by their voters.

The Social and Democratic Labour Party and the Ulster Unionist Party, which had dominated Ulster’s politics for several generations, were turfed out.

Replacing them were the parties that had flirted with violence (the Democratic Unionists) or had been formally aligned with terrorists (Sinn Fein). Hundreds of political prisoners who had murdered for their cause were loosed on to Northern Ireland’s streets.

In due course, Sinn Fein became the largest party in Ireland in 2020 and the largest in Northern Ireland last year. The party most aligned with a terrorist group was rewarded not with less power but more. But peace, imperfect and, one could argue, morally compromised, did obtain as a result.

What would doing the same in Israel look like? Hamas was something of a known quantity even before the bloodletting of October 7. But that day of infamy should make the most naively optimistic progressive question the wisdom of an Irish solution.

Sinn Fein-IRA had an interest in sharing power with their opponents. They did remarkably well from this pragmatism. Hamas and its backers see no profit in a deal with “the Zionist entity”. Hamas exists to destroy that state and all its people.

The Irish peace process played out in a benign international setting. The end of the Cold War made the issue of negligible concern to the superpowers. The US could afford to take risks for peace because failure wouldn’t matter.

US president Bill Clinton reasoned that locking terrorists into a peace process was a win-win. If they disarmed and learned democratic politics: a win. If they were exposed as frauds they could be sidelined: another win. US support for Israel, in contradistinction, is fraught with risk.

The Irish Troubles never presaged a wider regional war. The war in Gaza does.

Every great power has a stake. America’s enemies, such as Iran, are exploiting it to weaken an already wavering US commitment to the region. Russian leader Vladimir Putin could not contrive a better way to sap US resolve in Ukraine than making it focus on Israel.

Chinese leader Hu Jintao did not make his Taiwan strategy contingent on Clinton’s in Ireland. But Hu’s successor, Xi Jinping, certainly is watching how Joe Biden handles Israel. Clinton’s Irish meddling was easy foreign policy. Biden’s Middle East diplomacy is the hardest.

Progressives like to see the Irish peace process as a victory for, well, process, of the superiority of jaw-jaw over war-war. They insist now that Israel and Hamas must talk. This forgets the crucial ingredient of peace in Northern Ireland: exhaustion. Old gunmen in their 50s and 60s wanted something different for their kids. Hamas does not.

Ideological republicans came to the negotiating table not from strength but fatigue. In the ’90s, they had faced a fierce resistance not from the British government – which just wanted the issue to fade away – but from their local opponents, loyalist terrorists who were prepared to kill and torture IRA members (and ordinary Catholic civilians) more quickly than the IRA could kill them. This exhausted stalemate is the reason the Irish peace process stuck.

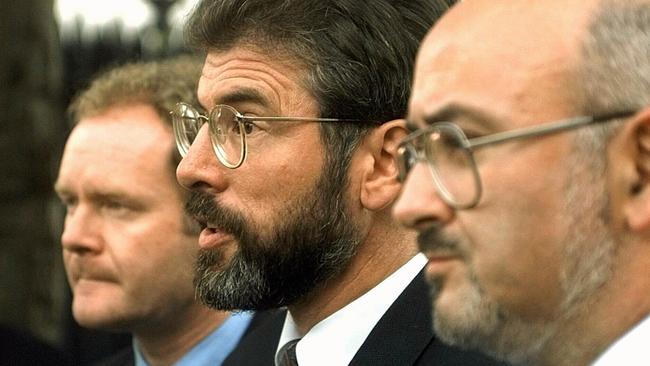

So, if how Ireland found peace has any lessons for Israel, it is an uncomfortable one: Hamas must be exhausted and destroyed, its will defeated, before peace is tenable. And Palestinians will then need leaders of guile and pragmatism – leaders such as Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness – to grasp some sort of victory from this defeat. It does not have those leaders yet.

Yeats went on, inadvertently capturing the extremism now ranged against the Middle East’s only liberal democracy: “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned; / The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”

Timothy J. Lynch is professor of political science at the University of Melbourne and author of Turf War: The Clinton Administration and Northern Ireland.

I once asked a senior Ulster unionist politician, fresh from a Middle East tour, what the difference was between the Northern Ireland and Israel-Palestine conflicts. The difference, he said, was there they really hated each other.