Recognition doomed by overreach on voice

So far off the rails, in fact, that in the past week or so one Indigenous leader, Noel Pearson, has accused another, senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, of being caught in a “redneck celebrity vortex” and “punching down on black fellas” just because she thinks the voice ill-advisedly divides us by race. Another, Professor Marcia Langton, has accused Price of pursuing “eugenicist” politics “about the superior race versus the inferior race” while weirdly calling for an end to “divisive politics”.

Our country is in more trouble than I thought if this is the tenor of the debate to come if the voice proposal proceeds to a vote.

In his recent McKinney lecture, respected Jesuit priest and lawyer Frank Brennan, a long-term thinker about Indigenous issues, summarised the dilemma our country faces 15 years after prime minister John Howard committed us to some form of Indigenous constitutional recognition. Can we, Brennan asks, “design a voice which does not divide the nation? Can we design a voice which doesn’t mean you’re going off to the High Court every day? Can we design a voice which doesn’t clog up the system of government? These are the difficult, practical and complex questions that need to be addressed.”

That’s where Brennan thinks we’ve arrived as a nation after first collectively agreeing that Indigenous people should be constitutionally recognised but then, in essence, allowing Indigenous representatives to work out for themselves what form this recognition should take – only to find ourselves confronted with the proposal for a voice that isn’t just symbolic recognition but “something more substantive put into the Constitution”.

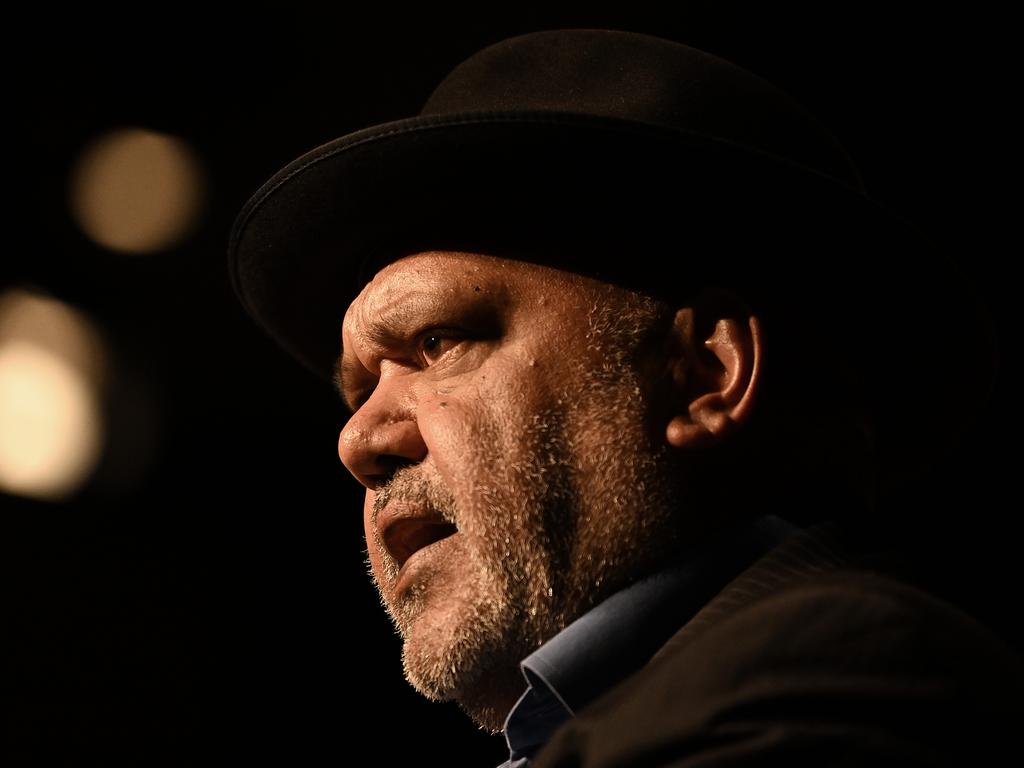

Pearson’s position, expressed with the moral thunder of a Moses coming down from the mountaintop, is that all Australians, including former prime ministers and Indigenous senators who support recognition but not necessarily the voice proposal, are “obliged” – obliged, he declares – “to respect the outcomes of a serious democratic deliberation undertaken with hope and sincerity by the least powerful community in that system”. Anything less than acquiescence on the voice, he clearly thinks, would be a contemptuous dismissal of Indigenous people. For the moment he doesn’t call it racist but, clearly, that’s what’s coming.

Yet there was nothing especially democratic about the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart that called for a voice, along with treaties and a so-called truth-telling process, and that denied sovereignty over this land had ever been ceded. It was simply a large gathering of Indigenous leaders, some of whom, including senator Lidia Thorpe, walked out in protest for various reasons.

There have been consultations commissioned by successive governments that came up with various proposals for ways in which recognition might be achieved, ranging from an anti-discrimination clause to a more limited voice than the one the Albanese government is putting forward, but none of these has been subject to any “democratic deliberation”, to use Pearson’s phrase.

Indeed, the only outcome of a democratic process so far has been the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Act that Julia Gillard as prime minister and Tony Abbott as opposition leader put through the parliament in 2013. This declared that Australia was “first occupied by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”; acknowledged the “continuing relationship” of Indigenous people “with their traditional lands and waters”; and respected the “continuing cultures, languages and heritage” of Australia’s Indigenous peoples.

Considering that it went through the parliament with bipartisan support, this would have been a far better basis for constitutional recognition than the Uluru statement. After all, the Constitution has to belong to all of us, not just to some of us, even those hitherto unjustly left out.

Given, though, that a fair body of Indigenous leaders has asked for something, how should we proceed, Brennan asks. We would need to consider, he says, “which of those Indigenous aspirations are morally justified” because “you wouldn’t want something set up as a voice that actually divides the country … that results in a situation of separatism driving Australians apart” and “you wouldn’t want to set up something that undermines the sovereignty of the Australian parliament”. Finally, Brennan says, “we have to be asking ourselves what is politically achievable … because the last thing you’d want, especially in this field, is a referendum that is bound for failure”.

Brennan does not say aloud that the current voice proposal is doomed but from the questions he poses seems to think that’s likely.

There’s the problem of a voice that’s both to the executive government and to the parliament, giving it two goes at governance.

There’s the problem of what should actually be subject to the voice: only measures specifically directed at Indigenous people or everything that might affect them.

There’s the problem, alluded to by former chief justice Murray Gleeson, that Australians “would want to … hear what the voice sounds like before they vote on it”.

Finally, there’s the issue of whether any voice should be included in the Constitution itself, and hence justiciable, rather than just set up by the parliament.

Noting Howard’s recent statement that “people are suspicious of the idea of a voice” that won’t “unite the country the way the 1967 referendum did” because “people see the voice as creating potential divisions”, Brennan observes that Howard “hasn’t lost all his political clout” before concluding “we’ve got a lot of work to do” if this voice is ever to succeed. You can say that again.

This is the fatal flaw in the voice proposal. It isn’t the recognition on which everyone is broadly agreed. Instead, it’s subjecting all the processes of government to a form of Indigenous vetting. The only way such a proposal could possibly pass at a referendum is through pretending it’s less than it is; that it’s really just a requirement that Indigenous people be consulted on the matters that affect them and nothing more. Even then, as we have seen, the plan is about telling voters as little as possible about what’s proposed in the hope that goodwill alone gets it over the line and people don’t wake up to the broader co-governance model that lies at the heart of the voice movement.

As the New Zealand experience shows, the Waitangi Tribunal, intended to have purely advisory functions to help redress Maori grievances, has become in effect a binding, quasi-judicial body by virtue of expansionist interpretations by activist courts.

I can’t think of anything that would divide our country more than a referendum that fails because voters see through the spurious reassurances of its proponents; or one that succeeds only to leave many of those who supported it subsequently feeling they were conned. Especially if the voice’s early concerns aren’t practical ones such as the problems of substance abuse and school non-attendance in remote communities but demands for treaties and reparations for dispossession.

There is a world of difference between the recognition that almost everyone supports and the Indigenous co-governance the voice represents. Voice supporters need to ask themselves whether this overreach should be allowed to jeopardise the recognition they say they want.

There is a vast difference between recognising Indigenous people in the Constitution, for which there’s all but universal support in principle, and a constitutionally entrenched Indigenous voice to parliament that goes beyond recognition and into the area of governance. That’s where the whole recognition debate has gone off the rails.