False alarms overstate the risks of Indigenous voice

It would be a pity if the impressive Jacinta Price allows her career to be framed forever by her opposition to a conservative idea of a fair go.

The party has been beguiled by the cut-through rhetoric of their novice Northern Territory senator, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. With this strong, articulate and media-savvy newcomer dominating the fledgling No case nationally, winning plaudits from many conservative supporters and commentators, it seems Littleproud and his frontbenchers decided they had spent too long in her shade.

After Littleproud made the announcement at a courtyard press conference in Canberra, Price fronted the media, making stronger and more cogent arguments than her leader, with a clutch of middle-aged white men, and some women too, providing the backdrop. Few politicians have had as much impact on national debate within six months of being elected as Price, but she needs to be wary of flying too close to the sun.

Public support for the voice is strong. Despite the best efforts of some, the idea does not generate fear among most voters and there is every chance the referendum will succeed – with or without the Nationals.

It would be a great pity if the impressive Price, who came to parliament primarily as a voice for grassroots Indigenous Australians, allows her career to be framed forever over opposition to a broader Indigenous voice.

Instead she could have been a constructive figure, ensuring the voice is as practical and representative as possible. The Nationals have now counted themselves out of the public debate in a premature and unwise fashion; Littleproud’s scattergun justifications made that clear.

Price made a better case about wanting to avoid another level of bureaucracy, but her claims about not wanting to be “governed” by a “race-based” body is just plain wrong and typical of the inflated rhetoric being used to drum up antipathy.

Some Liberal conservatives will want to follow the Nationals’ lead while others, and the moderates, will want to seize the chance to differentiate from their Coalition partners, support the voice and demonstrate the party is pragmatic rather than anachronistic. There is already a push within the party to allow a free vote on the issue.

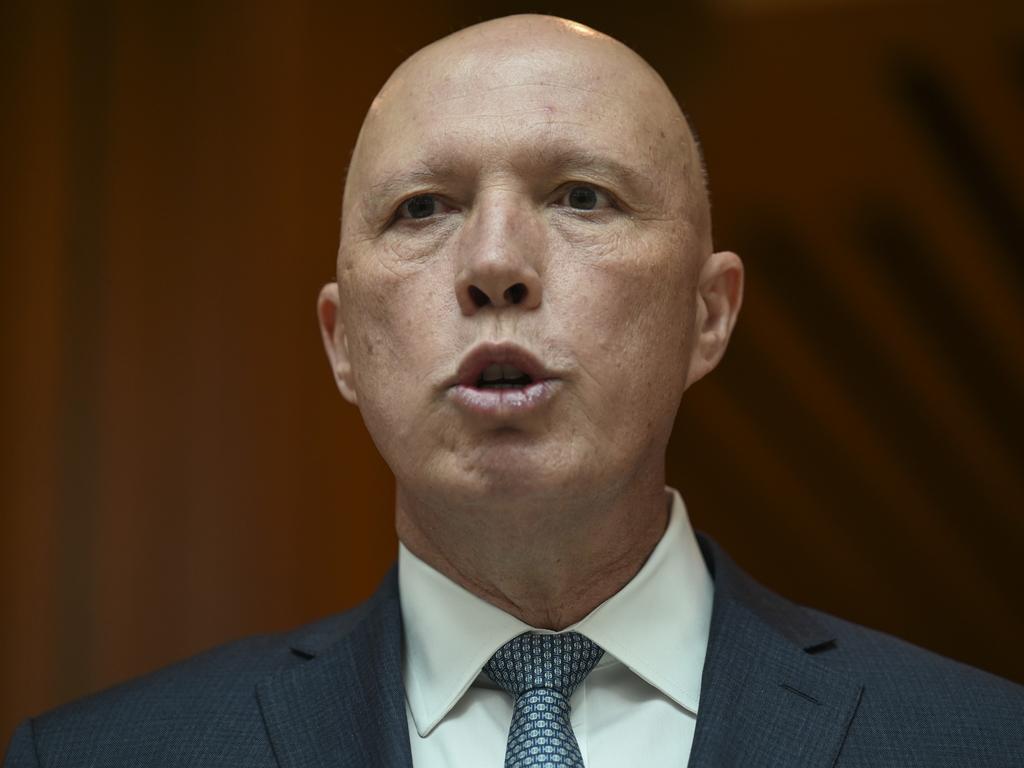

It is difficult to imagine Peter Dutton opposing this referendum because if he fought it and lost, his career would be over and the Coalition parties would be sidelined. Even if the referendum were defeated narrowly, perhaps getting a majority of votes but not in the majority of states (as might be his best hope) it would leave the Opposition Leader and the Coalition tarnished as spoilers.

If the conservatives in Dutton’s party are intransigent, a free vote might be his best option. But it would be far better for Dutton and the Coalition in the medium term if he and Price could hold out an olive branch, involve themselves in the process.

You have to choose your battles. And the Coalition is not short of areas where it needs to sharpen the contrast with Labor.

Part of Littleproud’s argument this week was that there had been too little consultation with Indigenous people about the voice structure and that Indigenous communities in regional and remote communities needed to be heard in Canberra. Given this is the aim of the voice proposal, his words could well have been voice advocacy rather than denunciation.

It was under the Morrison Coalition government (in which Littleproud was a cabinet minister until six months ago) that a detailed co-design process was undertaken. This was for a legislated voice, to be sure, but three committees of mainly Indigenous representatives consulted thousands of Indigenous people across the length and breadth of the country, producing detailed recommendations about a structure or local, regional and national voices, and noting the strong preference among Indigenous Australians for such a project to be enshrined in the Constitution.

Littleproud, the Nationals and other voice opponents cannot pretend away all this work, nor the Coalition goodwill – it is why the complaint about lack of detail has been largely fallacious. Former Coalition indigenous affairs minister Ken Wyatt, who drove the process, reminded the Nationals of all this during the week.

To argue the voice will not work, will be too bureaucratic or will be overrun by radicals, is really to trumpet your own impotence. It is up to the body politic to ensure this is not the outcome; parliament has the authority and responsibility to manage these outcomes. It is not as if ineffectiveness, creeping bureaucracy and radical activism are not constant threats to every other area of representative democracy.

All these issues have been confronted by Labor and Coalition politicians, state and federal, and almost all of them agrees Aboriginal advisory bodies are essential for good governance and overcoming Indigenous disadvantage. Victoria already has a state voice and South Australia will legislate a body soon. So, there will be voices. Denial is not an option.

Given all this, the core argument again becomes clear. We get back to the single sticking point – constitutional enshrinement of the voice.

If we put aside the fearmongering about “race-based” division, replete with “apartheid” comparisons and even an “Aboriginal-only parliament”, we are left with two main arguments from opponents that need to be addressed. One is legal, the other ideological.

The legal argument has been most diligently expressed in these pages by Janet Albrechtsen. In short, it says that enshrining the voice will lead to litigation and judicial activism that will see the voice used to expand power and usurp the will of parliament.

This is an entirely appropriate area of concern for any change to our Constitution, and it is incumbent on anyone proposing changes to demonstrate that new clauses, as far as possible, will not have unintended consequences. But considered opinions from former High Court chief justices Murray Gleeson and Robert French, not to mention a raft of other constitutional law professors, have provided significant reassurance.

The intervention this week by former High Court justice Kenneth Hayne further allayed concerns because he assessed the exact constitutional wording currently proposed.

“So what exactly is this fear that is raised when it is said ‘Oh, the courts will get into this space’?” posed Hayne. “I think the more you look, the less there is to see. The fear is baseless.”

Albrechtsen’s retort saw this as an admission that litigation might proceed. Yet surely we assume that at some stage, someone will test most aspects of our Constitution, especially contentious new clauses; the question is whether the clauses bear up – and Hayne’s view is clear.

Besides, if Albrechtsen or others believe the clauses are not tight enough, there are really only two options: propose alternative wording or declare it is beyond the nation’s collective wit to get this right. We ought to be able to do this.

The legal argument is one of absolutism, suggesting that it is impossible to draft the perfect and impregnable voice clause, therefore the reform should be abandoned. A similar argument is often put regarding the republic, where it probably carries more weight given the importance of reserve powers and conventions, but with the voice it seems more like a proxy debate to try to make the concept of a voice seem impossibly risky.

Remember, there is a failsafe option here. If a voice proved to be irreparably damaging, even after legislative changes by parliament, the requirement to have a voice could be overturned at a subsequent referendum – not a likely scenario, but obvious insurance.

The ideological debate rests on a similar level of absolutism and it too has been made most eloquently in these pages, by Greg Sheridan. He argues that the voice is “a direct repudiation of the central tenet of political liberalism, because it strikes against universal citizenship”.

Sheridan defines the voice as “race-based” and a capitulation to identity politics. This is intellectually sound and ideologically understandable, but it ignores the pragmatism of the real world.

This demonstrates where the ideological approach of liberalism fails the practical approach of conservatism. A conservative approach looks for pragmatic ways to deliver those liberal ideals of equality.

Without getting bogged down in semantics, it is important to understand the voice is not race-based. The push for an Indigenous voice is not based on racial characteristics or assumptions; rather, the nation’s original inhabitants need a voice because they were specifically excluded from the Constitution initially, have been subjected to specific laws and policies, were found under law to have inherited special rights to native title and the like, and they remain, as a cohort, the most disadvantaged group in the country.

If we were to go with Sheridan’s strict liberalism about treating all people in an identical fashion, we might not tolerate special services for the disabled, allow religious schools, grant maternity leave or even provide the Age Pension. We often choose to tailor our approach for certain groups – this is not inequality or discrimination, it is the opposite.

Under the strict interpretation outlined by Sheridan, how would we justify the departments of Indigenous affairs in all the state and federal governments, and Indigenous affairs ministers and a range of other organisations and services? We also have native title legislation, Aboriginal heritage legislation and special programs for Indigenous health, education and employment.

If none of this is an affront to our innate equality, then neither is a voice. There is nothing about the voice proposal that seeks to confer special privileges on Indigenous Australians; it is all about redressing disadvantage simply by giving Aboriginal people a non-binding, advisory say on matters that affect them.

It should encourage accountability, encouraging Indigenous communities to own the outcomes of policies they recommend. The voice should not be seen merely as a proposed new right but also a new responsibility.

The voice is a conservative idea to deliver a fair go to Indigenous people, and to ensure Indigenous aspirations to constitutional recognition are realised in their preferred practical way, rather than through mere symbolism. If it is implemented effectively, run diligently and embraced widely, it just might help make a difference.

It is contradictory and disingenuous to proclaim a proposal is vague and lacking sufficient detail for proper assessment but then to oppose it, before that detail is presented, on the basis that it is bureaucratic, unrepresentative and ineffective. This is what the Nationals have done on the Indigenous voice under their leader, David Littleproud.