In a world of chaos, Queen Elizabeth II stood firm. She spent her last days upright, attending to royal duties in a final stand of defiance against her ageing frame. She was a model of modesty and self-restraint in a culture confounded by freedom set adrift from its moral moorings. Hers was a generation that witnessed the world at war and knew the horror of unrestrained passions among men. They came to value social decorum, religious ritual, emotional restraint, family piety and duty before pleasure. Subsequent generations have celebrated a progressive loss of respect for each.

The Queen was dedicated to God, country and family while accepting with grace the epochal changes that her long reign brought. She was a symbol of British Empire who oversaw its transformation into the Common-wealth. Its dissolution was a gradual process from limited self-government to recognising the sovereign independence of former colonies during the 20th century. Perhaps the most dramatic period was during the process of decolonisation that took place from India’s independence in 1947 to 1997 when Hong Kong was returned to China’s administration.

Many former colonies chose to join the Commonwealth of Nations. However, the Queen did not take lightly the brutality of imperial rule that preceded it or try to revise history. In a speech to commemorate India’s independence, she recalled the horror of Jallianwala Bagh, a massacre of 379 Indians following violent protests against British rule in 1919. Last week, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi graciously remembered her as the personification of “dignity and decency in public life”.

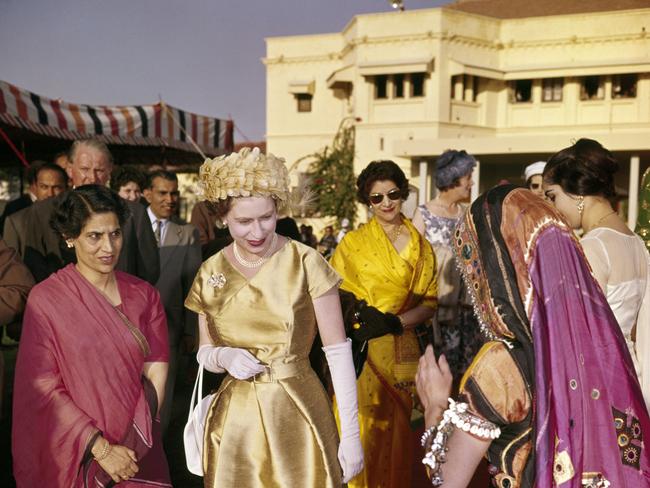

The modern monarchy rose from the ashes of colonisation and marked a new Elizabethan age. On her coronation in 1953, Elizabeth II was proclaimed Queen and Head of Commonwealth. She took the role seriously, embarking on a tour of Commonwealth nations from 1953 to 1954. That former colonies willingly entered into the new alliance of nations dedicated to democracy and peace is a testament to her diplomacy and the high regard in which she was held.

We live in a century ruled by the Furies where anger is currency and slander is gold. The Queen represented a kind of counterculture against common rage and taught by example that there is strength in silence. In recent times, she refused the lure of the swill as her grandson and his wife broadcast gossip about the royal family on television. Over many decades, she has encountered similarly testing situations that would have provoked the spirit of anger in most. But she has maintained the iron discipline of emotional restraint and turning the other cheek.

Among her most ardent critics are anti-monarchists quick to capitalise on her death by taking her demise as a sign the republic was within reach. And King Charles’ reign could prove to be a challenging period for monarchists. Historically, he has erred by deviating from the apolitical, temperate path that gave his mother’s reign a dignified and transcendent quality. He lacks the popular appeal of Prince William and Princess Catherine. It is, of course, to the King’s credit that his eldest son is so well regarded. But for many, the image of King Charles and the Queen Consort is inextricably bound to the memory of his first wife Diana, who said in an infamous Panorama interview: “Well, there were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded.”

Despite the controversy, King Charles’ second marriage seems to have produced a sense of stability so lacking from his first. In his speech to the Accession Council, he thanked his wife and prayed for “the guidance and help of almighty God”.

Elizabeth II benefited from a conservative temperament that equipped her for a life dedicated to duty and a long marriage to the late Prince Philip with whom, it seems, she fairly liked to flirt. There is an endearing photo of them in later years straining to observe protocol but failing to suppress mischievous giggles as she walks by him standing erect in uniform. After his death in 2021, her health faltered.

Elizabeth II held the Crown at a remove from politics, leaving a legacy shaped less by temporal affairs than enduring civilisational values. She built her foundations on universal virtues that make life meaningful and nourish the good in society: duty, self-discipline, humility before God, a charitable spirit, a fine sense of humour, moderation in most things and excess in none. Hers was a life dedicated to public service, royal ritual, the values of permanence and the form of freedom that Christian tradition inspires. In a memorable wartime broadcast on the BBC, she consoled children: “We know, every one of us, that in the end all will be well; for God will care for us and give us victory and peace.”

We will never be royals, but we can assume a regal air, liberate glamour from the dead hand of domestic minimalism, find the fine white linen napery, fetch the heirloom silver, polish the crystal and raise a glass to the Queen; a meat- and-two-veg girl fond of gin, jam, horses, corgis and a cheeky flirt with her husband. Here’s to Elizabeth II: a jewel of the realm, the Queen who never quit and the best empress we never had.

Queen Elizabeth I ruled over the dawning British Empire in the 16th century. Queen Elizabeth II reigned as it was eclipsed by 20th century modernity that brought mass movements for social liberalism and sovereign self-determination. Her legacy is a modern Crown sustained by moral example and the values of British civilisation writ large on humanity.