This conservative fusion of freedom, family and nation is still contentious in the Anglosphere. Yet in places such as Hungary a colony of English-speaking public intellectuals has sprung up, centred on Budapest. Here thinkers are keen to come up with a modern formula that can “unite the right” and end the civil war inside established centre-right parties between their conservative and their progressive wings.

This internal struggle is not, as often claimed, between conservatives and liberals, but between conviction and opportunism. Because it’s not really liberalism that’s now at war with conservatism; it’s progressivism: manifested inside centre-right political parties via the notion that electoral success means moving to the left in order to pick up centre-left votes, because right-wing voters have nowhere else to go. The trouble with moving to the left in order to gain new voters is that it normally infuriates old ones, who naturally feel betrayed by a party that no longer knows what it stands for; and can opt out of politics altogether, or support minor-party disrupters than can make a bad situation even worse.

At least in the English tradition, liberalism has an honoured place within conservatism. Tennyson’s description, “A land of settled government, a land of just and old renown, where freedom broadens slowly down, from precedent to precedent”, nicely encapsulates the mostly happy marriage of liberalism with conservatism, at least in English-speaking countries. But English liberalism backed an intensely pragmatic freedom, far removed from licence or even libertarianism, that could never be prejudicial to good order or to the country’s success.

In free countries that have steadily become richer, there’s been a slow yet seismic shift: working people – who are normally pragmatic, family-focused, wanting services that work, with more jobs and higher pay – have been voting more right; while well-to-do people – who are often ideological and internationalist, because they have less to worry about in their own lives – have been voting more left.

This should not unduly worry political conservatives, because it stands to reason that a conservative party that’s broadly in tune with working people’s thinking should be more electorally successful than an establishment party, from the simple fact that the relatively poor are normally more numerous than the relatively rich, even in countries as blessed as those of the West still are.

But if working people are voting more right: as in Australia in 2013 (my election), America in 2016 (Donald Trump’s election) and Britain in 2019 (Boris Johnson’s Brexit election), the main party of the right needs to adjust to become more economically pragmatic; more focused on the social fabric, more targeted towards people’s living standards, and more concerned to uphold its own country’s interests over “global” ones.

And if richer people are voting more left, as in the teal phenomenon in Australia in 2022; the Tory wipe-out in London in 2019, and; Joe Biden’s sweep of all the big US cities in 2020, the main party of the left will change too, to focus less on cost of living, and more on “First World problems” like climate and identity, and be vulnerable once more to losing the old “blue-collar Tories” and the “Reagan Democrats”.

Voting statistics show that parties of the right have tended to become more working-class parties, in the sense that their support comes from people who have to work hard for a living; while parties of the left have tended to become renter-class or welfare-class parties, for people who get their money from the state, or from their investments.

This should not worry conservatives, even though it creates quite a different political contest from the old one, where the parties of the right preached more freedom and lower taxes while the parties of the left preached more fairness and better services.

The new contest doesn’t mean conservatives can ignore economics, because there can be no decent society without a strong economy to sustain it, but sensible economics becomes less an end, and more a means: to a better health system, a more rigorous education system, a social security system that strengthens the family, and a strong national defence. This is potentially a larger constituency than one based on giving the market its head.

Difficulties only arise when the mindset of the party leadership doesn’t adjust to reflect this new voting reality; and to appreciate how the party’s voting base has changed: when the party’s leadership remains drawn to the climate and identity fixations of the already well-to-do suburbs while its voters have migrated to more aspirational ones.

Boris Johnson, for instance, was in tune with the “red wall” on Brexit, but not on emissions reduction – which working people see as an economic issue, with renewable energy driving up their power bills; but which richer people see as a moral issue to be pursued at almost any cost in order to save the planet. Donald Trump, for all his crassness, is perfectly in tune with the “left-behind” Americans of the “flyover states”, which is why he so convincingly won the Republican primaries.

Supporting high immigration with more or less open borders, because it creates larger markets and a pool of cheap labour for big business, or because it’s somehow owed to the Third World, or because it creates the illusion of economic growth while GDP per person stagnates, is toxic to conservatives’ working-class constituency, because it depresses wages, lifts housing costs, and clogs infrastructure, and can set up clashes between poorly integrated communities’ values and mainstream ones.

And equally toxic is obsessing over emissions and making false claims that renewable energy is cheap; while the field evidence is skyrocketing power prices, industries moving offshore, landscapes blighted by expanses of solar panels and forests of wind turbines, with unelected climate tsars increasingly issuing edicts over the food we can eat and the cars we can drive.

These days, if it can’t control immigration and if it succumbs to the climate cult, any votes a conservative party might pick up on the left will be more than matched by the votes it will haemorrhage on the right. Trump gets that; in the end Johnson didn’t, and if Rishi Sunak understands it, he hasn’t yet acted on it, which is why the British government is now in electoral trouble.

As party leader, I always stressed that our job was to be a clear alternative to the other side, not a weak echo. Given the mess green-left governments are making – with crumbling services, declining productivity, stagnant wages, growing street crime, divisive and intimidatory protests that are becoming routine, propaganda masquerading as education, emasculated police and armed forces, and an uncertain response to dictators-on-the-march – conservative parties should be stronger than ever, provided they have decent leaders with the courage, the conviction, and the vigour to articulate clear positions in opposition and to pursue them relentlessly in government.

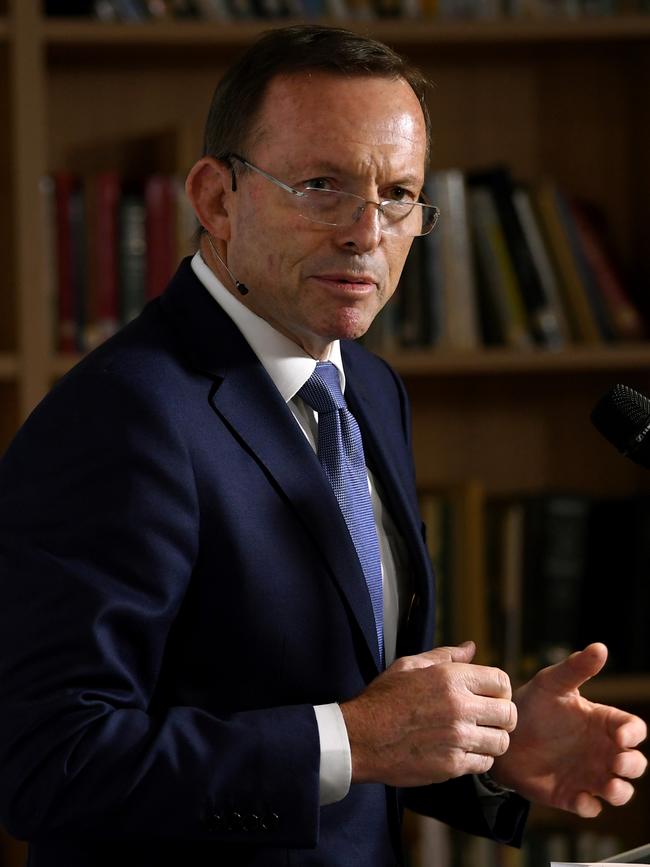

Tony Abbott is a former prime minister of Australia. This speech was given to the Conservative Political Action conference in Hungary on Wednesday.

The new conservatism is intensely patriotic, economically pragmatic and deeply respectful of tradition. As leader, I often said of the Liberal Party in Australia, historically a blend of conservatism and liberalism: “As liberals, we want lower taxes, smaller government and greater freedom; as conservatives, we support the family, small business and institutions that have stood the test of time; but above all, as patriots, we think that Australia is the best country in the world and want to keep it that way.”