The spiralling cost of the NDIS keeps federal officials up at night, and those in state treasuries fearful that there’ll eventually be a knock on their door to carry their share of what was always envisaged as a 50:50 funding split.

Because of the shifty cost shuffling in the provinces and lax definitions, Canberra is now funding 66 per cent of NDIS costs, and without amelioration looks like it is going to eventually be kicking in 82 per cent.

Anthony Albanese has walked lightly across the threshold to the suites of his counterparts in the national cabinet and if not quite cap in hand, he’s said “Come on mate”.

At the October budget, the NDIS was estimated to cost $35bn this financial year, and almost $52bn in three years’ time. At 15 per cent a year, it is the fastest growing program in the federal budget.

In a decade, it would cost $97bn, in the ballpark of what the feds spend on Medicare, hospitals and aged care.

That expected increase for the NDIS comes because more people are going to join the scheme and the cost of supporting an individual with more services is rising by 33 per cent above inflation. Six hundred disabled people are joining each month, with autistic children among the fastest growing cohorts.

By the end of the decade, the fiscal metrics are scary; this, ultimately, may prove to be an insoluble issue of the brain, the heart and the hip-pocket.

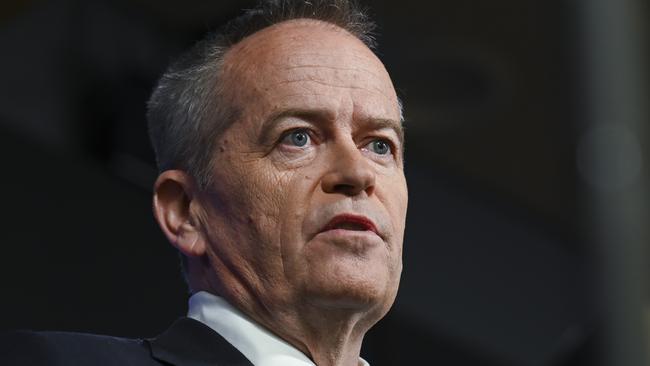

Bill Shorten laid out half a dozen reform measures recently, but his successor as Labor leader has stepped in to get premiers and chief ministers to do what they can, which at first blush doesn’t seem like much at all.

No one’s budget, other than frontier mining states fat with royalties, is in good shape because of the pandemic, transport and infrastructure binges, serial ill discipline with bureaucracies, and a downturn in property transfer duties.

The Prime Minister has managed to get his colleagues to “soft agree” to slow the rate of spending growth to 8 per cent a year over the coming three years with, he said in a triumph of hope over experience, “further moderation of growth as the scheme matures”.

Originally, growth in NDIS costs was anticipated to be 4 per cent, which Albanese explained is why the cap on spending from state and territory governments is 4 per cent. That horse has bolted.

To improve administration and oversight, Labor will be providing the agency with an extra $720m in the May 9 budget.

Experts say tackling fraud and running lean systems won’t, ultimately, be enough to make the NDIS sustainable.

What’s required are stricter eligibility requirements, which will be politically difficult if nigh impossible, and significant cuts across the board to stop, and then reduce, the billowing cost per participant.

It’s not yet an existential crisis, but nips and tucks, new frameworks, federal-state happy deals and stricter regulation on individual plans are all on the table. At last.

Plainly, the political class needs to pay a lot more attention and make a series of difficult calls, which won’t go down well with participants and the sharp industry that’s built up around them.

Even vision-impaired Freddy can see that.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme is a wonderful enabler, Labor and Coalition legacy and a swelling burden on taxpayers, meaning it’s in no one’s interest for this saviour program to implode.