There is discussion within Labor ranks about two choices the Prime Minister will contemplate across summer: whether to prepare for an early election, possibly in November or December next year, and a reshuffle of the ministry to prepare for possible departures and to elevate a younger generation of MPs to demonstrate renewal.

First, the likelihood of an early election. The thinking is if the government sees out the following year, by early 2025 the pre-election speculation will be at fever pitch. It will look like the government is dragging its heels.

Voters are angry and anxious about rents, mortgage interest rates and inflated goods and services, and this mood could worsen by waiting too long. So, an election in late 2024 is being canvassed as a better option than being seen to run down the clock until mid-2025. An election next year also could act as a circuit-breaker with the likelihood the government will be re-elected, as every post-war government has been.

But an early election is always a risk and re-election cannot be taken for granted. If history is a guide, we should brace for an election in late 2024 even though a full parliamentary term would mean an election in May 2025. Malcolm Turnbull and Julia Gillard took their first-term Coalition and Labor governments to elections a few months early in July 2016 and August 2010, but these were not really early elections.

But every other government post-war has gone to an early election. Robert Menzies went to an election in April 1951, Gough Whitlam went early in May 1974, Malcolm Fraser took the country to the polls in December 1977, Bob Hawke called an election for December 1984 and John Howard for October 1998.

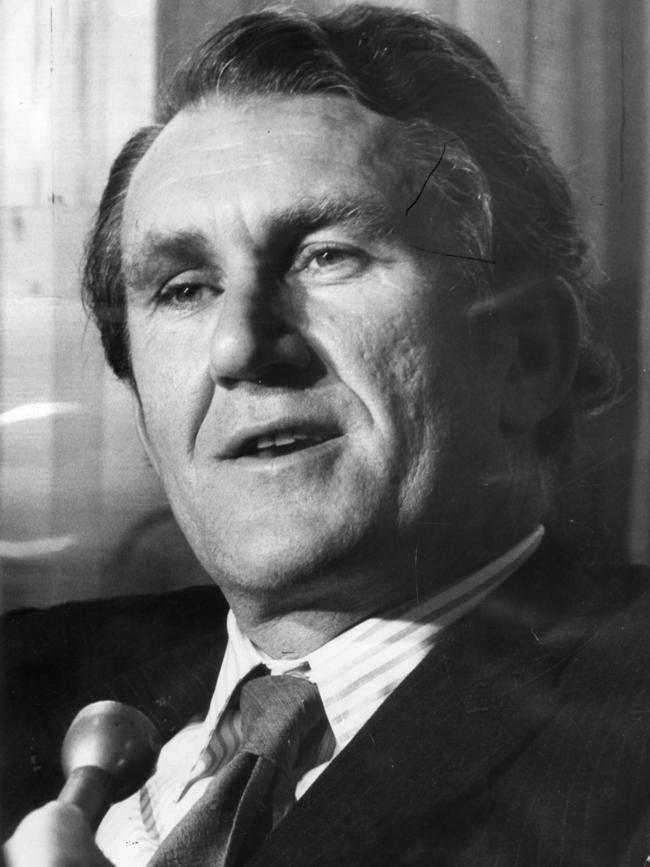

While these prime ministers felt they had to go early for various reasons, the results are not encouraging for Albanese. Menzies, Whitlam, Fraser and Howard all lost seats but were able to win re-election with reduced margins. Hawke gained seven seats in an enlarged parliament but the Coalition, led by Andrew Peacock, gained 16 seats. It was not a good result.

Albanese’s calculations about an early election are complicated by a redistribution of seats in Western Australia, Victoria and NSW. The two larger states will each lose a seat and the smaller state will gain a seat, reducing the size of the parliament to 150 seats. Labor has a three-seat majority. It holds four seats on margins of less than 1 per cent. So, the redistribution could be critical.

The second pressing topic of conversation in Labor is the likelihood of a ministerial reshuffle. The rumour mill is in overdrive about several ministers, all parliamentary veterans who served in previous governments, possibly tapping the mat and exiting the frontbench and parliament. Diplomatic appointments could be arranged.

Among the names mentioned are Foreign Minister Penny Wong, Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney, NDIS Minister Bill Shorten, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus and Skills and Training Minister Brendan O’Connor. Some or all of them may deny any intention to quit but that does not mean Labor MPs are not talking about them going.

There is an opportunity for generational change. The talent in Labor’s outer and assistant ministerial ranks is considerable. The better performers include Matt Keogh, Stephen Jones, Anne Aly, Anika Wells, Matt Thistlethwaite, Andrew Leigh, Patrick Gorman, Jenny McAllister, Ged Kearney, Emma McBride, Malarndirri McCarthy, Tim Ayres and Anthony Chisholm.

There is a third issue occupying minds in the party: an agenda for re-election. As noted last week, the Albanese government has been focused on delivering its election commitments but has struggled to present a coherent narrative to explain where it wants to take the nation and why.

Labor needs to better articulate its purpose for being in power, its overarching ambitions and goals that illuminate its vision for Australia. It has a big agenda that is far-reaching across the economy, society and environment. But policies need to be connected in a framework that speaks to values and principles with a persuasive argument for sticking with Labor.

Perhaps the biggest test for Albanese and Jim Chalmers will be managing expectations in the rundown to July 1 next year when legislated stage three income tax cuts begin. The key change is introducing a 30 per cent tax rate for incomes between $45,000 and $200,000. Unions, social welfare groups and left-wing think tanks are unhappy, arguing they favour the wealthy.

But these tax cuts were legislated with Labor’s support, a position Albanese and his Treasurer have reaffirmed. It would be a broken promise to repeal them. But with a bulging budget surplus, there may be scope to provide further tax relief for those on low incomes while keeping the benefits for aspirational and entrepreneurial middle and higher-income earners.

The government insists its focus is fighting inflation to alleviate cost-of-living pressures. Yet sticking with the tax cuts and possibly spending the surplus on even bigger tax cuts or cash handouts would only fuel inflation. That is why the government talks about cheaper medicines and childcare, increased bulk-billing, fee-free TAFE and boosting wages of the low paid.

The year ahead is filled with challenges and opportunities for Labor. After its worst weeks in power, it must spend the summer working out what it stands for and what it wants to achieve, contemplating renewal of the frontbench and the timing of the next election.

Above all, it needs to turn its mind to a reform agenda. Therein lies the pathway to a second term.

For Anthony Albanese and his ministers, 2024 will be a year of decisions that will determine whether his faltering government is granted a second term, who will have their hands on the levers of power, and the policies that will shape Australia’s economic, social and environmental policy settings for the following decade.