The Prime Minister is paying the price for years in opposition when Labor avoided hard choices on defence and foreign policy, instead claiming an unexamined bipartisanship. That counts for nothing in government. Without considered policy foundations the government must rely – like Scott Morrison – on instinct and quick reactions. As in Morrison’s time, these qualities are not always on display.

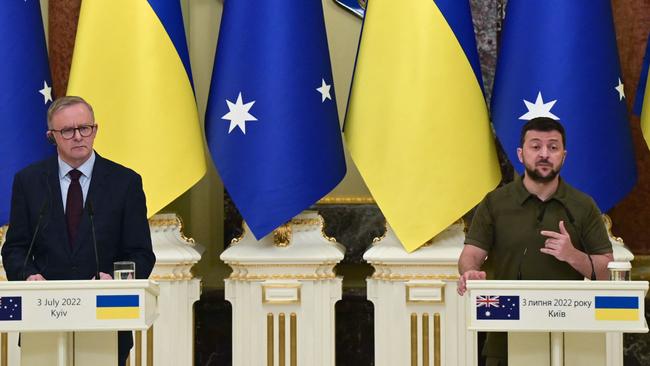

Credit where it is due: Albanese consistently has been right to support Ukraine with military and humanitarian aid and to denounce Russia’s brutal invasion. “I will remain, on behalf of the Australian people, a fierce opponent to Russia’s immoral and illegal invasion of Ukraine,” Albanese said on Wednesday.

The Prime Minister’s view on Ukraine is absolutely the correct one, based on understanding that democracies must help each other against aggressive authoritarian regimes. Albanese should use his trip to quash any wavering in international support for Kyiv.

Albanese’s trip, however, lacks a sharp policy point. In Cambodia Albanese will attend an East Asia Summit and an ASEAN-Australia Summit. Albanese says: “Australia strongly supports ASEAN’s central role in the region and its vision for the region is closely aligned with our own.”

But there is no achievable ASEAN vision for the region and “ASEAN centrality” is a diplomatic fig leaf. Southeast Asia has no counter to Beijing’s plan for dominating the region, driven by its military takeover of the South China Sea.

Australia’s influence in Southeast Asia, along with that of many developed democracies, is declining as the region tilts more to communist China.

Albanese says: “My role at these summits will be one of advocacy for not only Australians but also for those of our Pacific neighbours who face many of the same pressures that we do.”

Why does the Prime Minister want that advocacy role? How is it that Australia as a large, developed, continent-sized, energy-exporting powerhouse can claim to “face many of the same pressures” as a collection of microstates with few economic assets?

Australia has unique ties to the Pacific Island states and should engage sympathetically with their concerns. But we have no interest in subcontracting our policy concerns on climate (or any issue) to the island states, notwithstanding the ABC’s relentless advocacy on that front.

Australian media attention will be devoted to whether Albanese meets Xi Jinping. Spoiler alert: there will be a meeting. That much is clear from Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s call with her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, on Tuesday.

A risk for Albanese is that a handshake with Xi will be presented as a warming relationship. Handshake or not – Xi is not into hugging – there will be no change in the underlying strategic differences between Canberra and Beijing.

The reason Australia and China have had such difficult relations during the past few years is because the countries have different aims: China wants to dominate the Indo-Pacific. It wants to reduce the influence of the US by weakening America’s alliances and making regional states more dependent on China.

Australia will accept none of this. Having denied the problem for years, since the last half of Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership, Australian governments have resisted Beijing’s political influence buying, economic coercion and attacks on alliance co-operation. Albanese won’t change this approach.

The problem is that no Australian government in the past decade has been courageous enough to explain what these big strategic trends mean, and that China’s continued regional assertiveness may well lead the Indo-Pacific into conflict.

The result is confusion about how to engage China.

This week we had the nationally embarrassing sight of West Australian Premier Mark McGowan meeting Chinese state-owned enterprises and so-called private companies in Perth, declaring “the state government is committed to strengthening our relationship with China into the future”.

The last thing Australia needs is more Chinese ownership of our critical infrastructure.

This creates vulnerabilities to economic coercion and, given the all-pervasive influence of the Chinese Communist Party and its intelligence agencies, the risk of cyber disruption to our economic interests.

Federally, Australia failed to prevent a Chinese foreign investment into lithium refining in WA. This is a strategically vital commodity for defence and energy transition uses. Even ultra-cautious Canada last week ordered three Chinese firms to divest ownership of Canadian lithium mines.

On Wednesday the NSW parliament passed legislation that opens the possibility of the Port of Newcastle establishing a container-handling terminal. The economic case for establishing a second container facility in competition with the Port of Botany is murky, to say the least, but what should concern Australians most directly is that the Port of Newcastle is on a 98-year lease, half-owned by Beijing’s state-owned entity, China Merchants.

China Merchants has been a key champion of Xi’s Belt and Road strategy, building debt-leveraged exclusive economic relationships with developing countries through port developments – such as Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port – and by controlling a vast global network of container traffic.

Could anyone really believe that it’s in Australia’s strategic interests to allow a Chinese state-owned entity greater control of our international supply lines?

The NSW parliamentary vote will force early federal consideration of a vital strategic decision: where to locate a new east coast navy base for nuclear-powered submarines. The Port of Newcastle along with Port Kembla and (less realistically) Brisbane Port were identified by the Morrison government as possible locations.

We will know in March next year if Albanese will proceed with nuclear propulsion when an AUKUS plan comes to government. Government ministers are talking as though this is already a done deal.

Readers can be guaranteed that the US as the provider of nuclear-propulsion technology will not allow a submarine base to be located near a Chinese-leased port. Beijing has lobbied vigorously against AUKUS internationally. How will that affect China Merchants and the Port of Newcastle and Albanese’s approach?

As a company, China Merchants is older than the CCP, but the party calls the shots. Last month Tian Huiyu, the former president of China Merchants’ bank arm, was expelled from the party for corruption. By such means Xi extends his authority and direction over every sizeable Chinese business.

Australia’s security is no longer just about the size and location of the Australian Defence Force. The safety of our critical infrastructure and our economic security are equally important. That means “business as usual” with Chinese companies and Chinese foreign investment is no longer just economics.

The biggest strategic challenge for Albanese is to shape and then explain a strategy for Australia’s national security in a way that previous Coalition governments failed to do. That reasonably could start with the security of the nation’s port infrastructure.

Anthony Albanese leaves Australia on Friday for nine days of international summitry at a time of global turmoil but with no clear plan about how to counter growing risks to our security.