Other times it’s no big deal, just an advisory committee, even though the term advisory appears nowhere on the ballot paper in the words of proposed amendment.

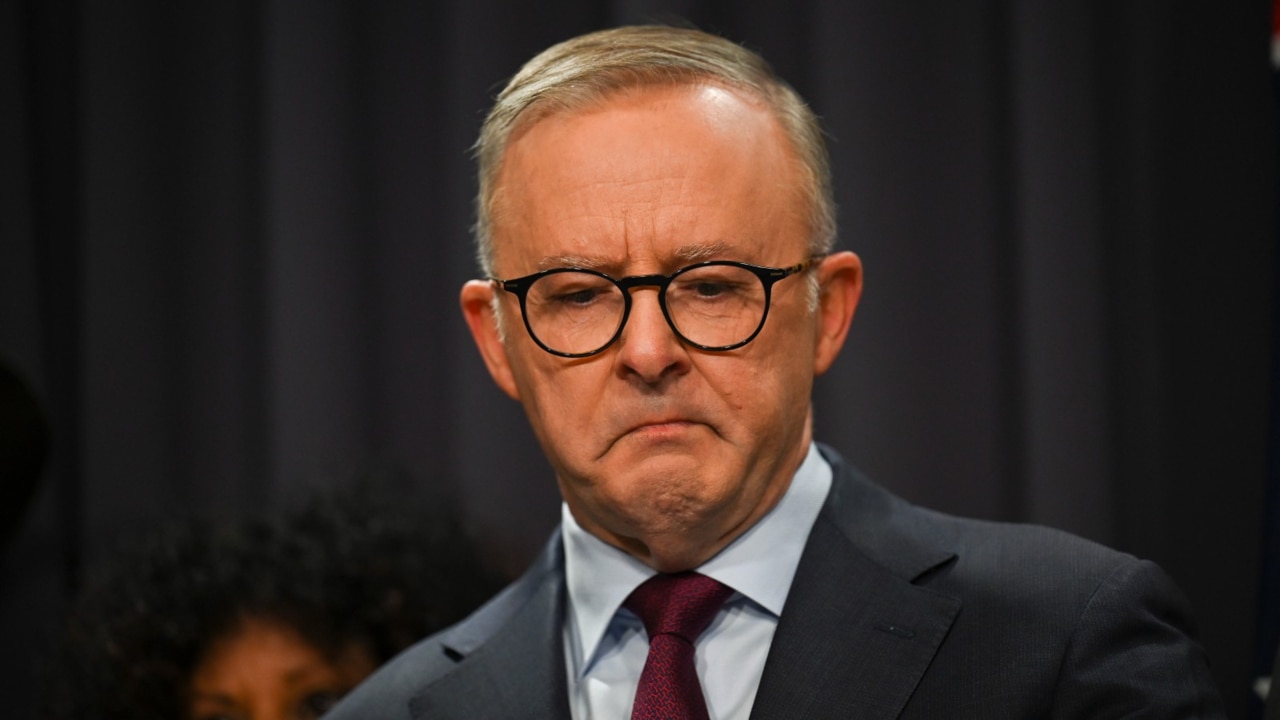

The more the voice has sunk in the polls, the more he has tried to minimise it.

His problem is that there’s just too much on the record maximising the voice for his current campaign of minimising it to seem anything but a tactic born of fear that it’s going to lose. And carefully chosen words out of focus groups to skate around legitimate concerns voters have about a proposal that he has never properly explained.

Even the Yes campaign’s official how-to-vote card, now being handed out at pre-polls, is entirely misleading, with a flowchart diagram suggesting it’s the parliament that will request advice from the voice rather than the voice proactively making representations to the parliament, and to the executive government. “Voice, treaty, truth” has always been the activists’ mantra. That was no problem for the Prime Minister when the voice had 60 per cent-plus poll support, when he said no fewer than 34 times that the government would implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart “in full”.

But now we actually know what’s in the full Uluru statement – beyond his spin that it’s a one-page poster, and now that all polls have the voice below 40 per cent approval – the last thing Albanese wants associated with his signature legacy project is a Makarrata commission, treaties, reparations and the abolition of Australia Day. Even though that has always been the agenda of the voice’s key architects.

Unfortunately for the Prime Minister, in the final fortnight of this campaign, the evidence of his earlier, more extensive ambitions are still all around, including (as of Wednesday afternoon) on his own website.

“This is not about a treaty,” Albanese reassured 2GB’s Sydney radio audience just a few weeks back. Yet his own website still carries Labor’s pre-election boast about being “the only party to support the Uluru Statement in full”.

“Delivering treaty & truth”, the Prime Minister’s website splashes, “fulfilling the promise of Uluru”, It goes on: “An Albanese Labor Government will establish a Makarrata Commission as a priority. This sits alongside Labor’s commitment to … a constitutionally enshrined Voice … in the first term” of a Labor government.

Further, says the Prime Minister’s website, “As called for in the Uluru Statement, the Makarrata Commission will have responsibilities for overseeing processes for Treaty-Making and Truth-Telling … (and) it will work with a Voice … when it is established”.

Critical here is the commitment to recommending “a framework for federal treaty-making, taking into account state and territory processes”.

So much for it being a mere advisory committee. So much for the Prime Minister’s push back in recent weeks against any role for the federal government in treaty-making when his own website trumpets the very opposite. And these are not the demands of the full Uluru statement (the longer document the Prime Minister still hasn’t read). These are the commitments of the Labor Party itself.

“The terms of reference for the Makarrata (Commission) … will include”, the Prime Minister’s own website says, inquiring “into matters of overarching national significance, including the causes of inequality from colonisation to the present day … as well as making an official record of colonisation, massacres, discrimination and resistance”. The Prime Minister’s website also commits that the “majority of (Makarrata) Commissioners will be First Nations Australians” (the majority!) and that $26.5m will be allocated to the commission for its first two years operation.

The Prime Minister can hardly deny that treaty and truth remain his iron-clad commitment as his government has already started spending on it, with some $6m initially allocated to the Makarrata commission in the October budget, of which Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney says $1m has already been spent, although she refuses to say on what.

Albanese should hardly be surprised at the voice’s vertiginous fall from favour when what he says now is so at odds with what he has said before. Every time the Prime Minister and his ministers try to minimise what they once maximised, voter doubts about whether the government is being upfront and honest grow stronger.

In a recent interview, Burney referred to the voice as no more than an “advisory body” or an “advisory committee” no fewer than nine times in an attempt to reassure voters that it shouldn’t worry them. Yet how many advisory committees get their own separate chapter in the Constitution, giving them a comparable status to the parliament, the executive government and the High Court? Any such committee would be more like a fourth arm of government, as acknowledged by two leading constitutional law professors, Nicholas Aroney and Peter Gerangelos, in their joint submission to the recent parliamentary inquiry.

Under the Constitution, as it’s proposed to be amended, this mere advisory committee will have a constitutionally guaranteed right to “make representations to the parliament, and to the executive government, on matters relating” to Indigenous people.

Given that Indigenous people are citizens, too, that gives the voice near carte blanche to make representations to everyone on everything. And a constitutionally guaranteed right to make representations would seem to imply a constitutionally guaranteed obligation to take those representations seriously.

On all significant government decisions, that means giving the voice adequate notice, adequate information and adequate resources to consider the issue and then to make a representation should it choose.

Plus it would demand the government decision-maker giving any representation adequate consideration before a decision. And at least until the voice’s remit is sorted out, any decision that isn’t to the voice’s liking will be straight off to the High Court, which will become the ultimate arbiter of what the voice can and can’t do, not the elected and accountable parliament and government.

If that’s an advisory committee, it’s far more powerful than any that has previously existed in history, which shows just how concerted is the campaign of voter misinformation now, to downplay the voice’s power, in the referendum’s final days.

Yet this attempted revisionism is undone by the voice’s own architects via years of prolific statements that constitutional power has always been the aim. Here’s constitutional lawyer Megan Davis: “Uluru was a sequenced reform, voice … first, treaty second”. What’s more, she has said: “Treaties are about reparations for past injustice and they are about land and they are about resources.” On another occasion, Davis has said: “Treaties are foundational documents between First Nations and the state. And they do involve a redistribution of political power.”

As Davis’s collaborator, Gabrielle Appleby, has said, the voice would provide “an important reordering of the hierarchy of the state (and) … transformation in Australia’s established constitutional institutions”.

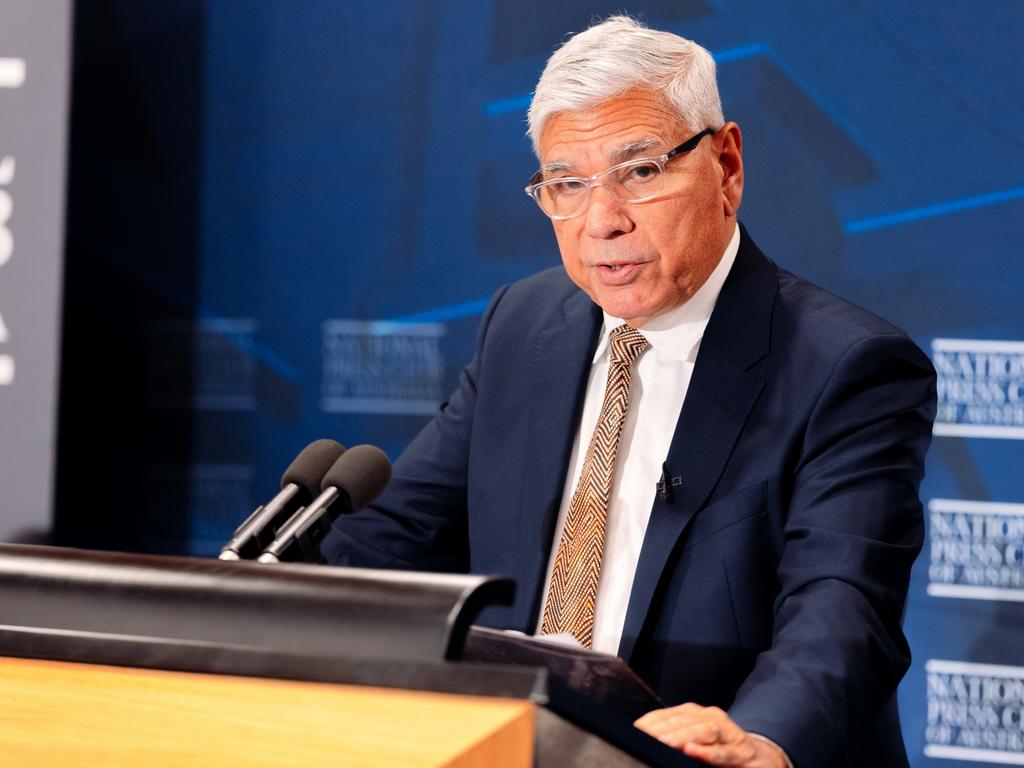

And at Garma last year Noel Pearson said: “For those of us who’ve come late to this strategy, you need to wake up. Treaty is the second door. The first door is constitutional enshrinement.”

Whichever way it’s looked at, the voice referendum is about changing Australia. It’s actually much more important than an election because a bad government can be rejected and a bad law can be changed, but a constitutional mistake is there forever.

Anthony Albanese has never been able to get his story straight on the voice. Sometimes the voice is a great historic change that will finally resolve all the issues afflicting some – but not all – Aboriginal people, close the gap and achieve reconciliation once and for all.