Where the climax of drought is smoke and fire, the counterbalance comes as a deluge of rain that can wash your house away.

The desperate situations playing out along Australia’s east coast are a product of meteorology, topography and the relentless cycle of nature. Weather systems fed by La Nina, a product of sea temperature changes in the Pacific Ocean, are sucking moisture from the atmosphere and dumping it by the metre.

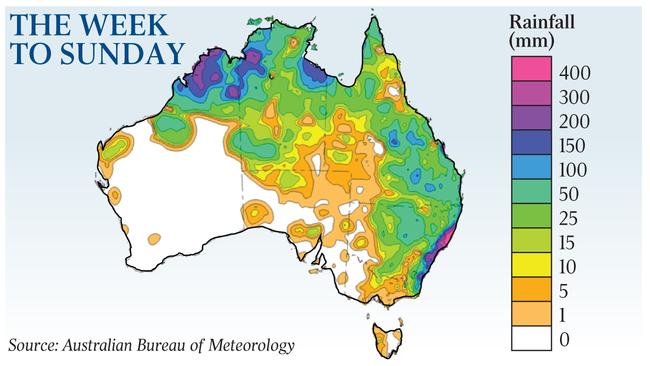

Australia has two main sources of moisture at work; a tropical low over northwestern Australia and a coastal trough off NSW. These two moisture feeds are merging and will create days of heavy falls across the continent.

Big catchments and choke points in the landscape are allowing the waters to build up and stretch across the plains as their path is blocked to the sea.

The physics of La Nina and east coast low weather patterns, and the geography of the major catchments, are well known.

Big floods have happened many times before and their impact is etched into the landscape, but every time they occur it is a confronting, dangerous reality.

The challenge of these floods adds to the trauma of deadly fires that scorched the landscape immediately before the breakdown of blocking weather patterns ushered in unpredicted rain this time last year.

For farmers, the recharge of soils has already brought bumper crops to make up for the lean years just passed. But where rivers, soils and natural systems are being recharged, major settlements are being inundated. Some areas, including Taree on the NSW mid-north coast, that were worst hit by fire are bearing the brunt of these floods as well.

Inevitably, the intense focus will be on Sydney’s outer reaches, where flooding already is declared the worst since 1961.

With heavy falls still to come, the Bureau of Meteorology says it is bigger than the 1990 flood, bigger than the 1964 flood and one of the biggest floods likely to be seen for a very long time.

The highest flood recorded in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley occurred in 1867 and reached 19.7m at Windsor. The 1961 flood (the highest in living memory) peaked at 15.1m.

The floods highlight the perils of urban development in the Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley, an area considered to be the most dangerous flood risk zone in the country.

The State Emergency Service has a short video to explain how five tributaries feed water into the system and natural choke points create a “bathtub effect” resulting in metres-deep water stretching over vast areas. Of the five tributaries, the Warragamba River has been responsible for 70 per cent of water in major flood events over the past 60 years.

Inevitably, the rising waters put a new urgency into debate about whether or not the wall should be lifted on the Warragamba Dam. The state government says lifting the dam wall will allow better flood mitigation.

Green groups have called on the UN to help block the project. They say flooding has recurred over centuries and allowing urban development in flood-prone areas is the real problem.

There are an estimated 5000 homes built below the 1:100-year flood line and plans for an additional 134,000 people to move on to the floodplain by 2050.

More than anything, the flood provides a reminder that the cycle of nature has not been broken.

At the height of drought the cry invariably is it will never rain properly again. But when the inevitable happens and the heavens open, the cry is heard that this has never happened before. Both sentiments are clearly wrong.