The history of the Liberal Party is adaptation to the changing norms of liberal capitalism and the quest for political advantage. The change has been vast — from the post-war protectionism, high growth and Keynesianism of the Menzies age to the fiscal restraint, open economy and pro-market reforms of the Howard age and then proceeding to the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison era that now constitutes a dramatic transition during its own lifetime.

Nothing illustrates this better than a recall of Tony Abbott’s arrival in 2013 and the political convictions invested in his government’s first budget.

This was a product of three forces — the belief that the 2007-13 Labor government spending was excessive and an electoral liability, a fidelity to the proven Howard-Costello model of budget restraint and fiscal stability, and a judgment that despite the global financial crisis the values of aspirational individualism and shared community sacrifice were still beating in the Australian psyche.

“Prosperity is not a gift,” Hockey said in his May 13, 2014, budget speech. “It needs to be earned … The days of borrow and spend must come to an end … The age of entitlement is over. It has to be replaced not with an age of austerity but with an age of opportunity.”

Assuming an optimistic view of human nature, Hockey said: “As Australians we must not leave our children worse off … We are a nation of lifters, not leaners.” His budget sought to reduce the deficit from 3.1 per cent of gross domestic product in Labor’s last year to 0.2 per cent in four years in 2017-18.

The macro strategy was correct but the implementation — the micro-decisions — were deeply flawed. Abbott and Hockey faced a near-perfect storm: hostility to reform, the charge of broken promises, a negative opposition, a fierce media and a lack of Senate control.

The successors, Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison, swore never to repeat these mistakes. Abbott-Hockey became the anti-model. Australia had changed — the grievance culture was strong in rejecting spending cuts and the entitlement mantra. Abbott and Hockey lost their jobs but they never recanted that their budget was in the national interest.

The subsequent Liberal governments began a journey of incrementalism, still seeking budget repair sufficient to cast Labor as irresponsible but prudent enough not to sacrifice office.

Morrison as treasurer was pushing the Liberals in a new direction — economic policy became less ideological and more pragmatic, social spending was a higher priority, risky supply-side reform was marginalised, the big end of town got fewer favours, household gains became the test that mattered, while fidelity to the balanced budget and tax cuts remained sacred turf.

Morrison’s constant search was for a better form of Liberal Party social contract.

When the pandemic hit last year it encountered in the Morrison-Frydenberg team the perfect Liberal government for the crisis. Neither was a prisoner of the past nor enslaved by ideological fixes. The Liberals had long decoupled from the 2014 moorings.

Morrison praised John Howard but was never an economic dry in Howard’s mould. The Frydenberg upshot was fiscal support of $291bn, beyond any earlier comprehension.

More significantly, the culture and political system had turned pro-market reformers into a near-extinct species as issue after issue was terminated; witness serious industrial relations reform, a carbon price, indirect tax reform and corporate tax reform. Any consensus for national interest economic reform had died a slow death.

It was Julia Gillard who set the prophetic tone for the decade with her big-budget National Disability Insurance Scheme and Gonski school deals, the message being that big-spending social reform was back as the culture shifted.

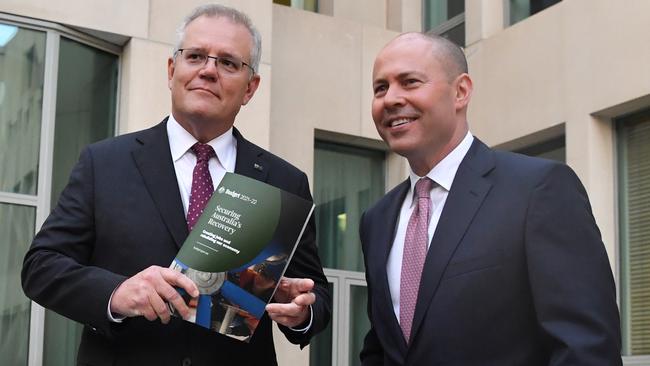

People looked to government to improve their lot in life and to deliver a better, compassionate, equitable society. When Morrison and Frydenberg drafted the 2021 budget they settled not just on more fiscal support. They made a critical appreciation — they decided Australia had not been spending enough on major social needs in aged care, disability and mental health.

The budget is more than fiscal pragmatism. It is a new departure in the Liberal social project that creates risks with fiscal sustainability. With spending running at more than 26 per cent of GDP during the coming decade — above the levels of the former Labor government — the budget remains in deficit in 2031.

A champion of the budget strategy, Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson says he is “stunningly proud” of what Australia has recently achieved but also warns when it comes to the bottom line “the government should have done more in the medium term”. Richardson says: “To imply this budget doesn’t come with a cost down the road is not bringing the electorate into your confidence.”

The budget comes with an implanted fiscal time bomb. Before the budget Richardson estimated that future annual savings of a huge $40bn a year would be needed to get back to budget balance. Post-budget he says this figure is now “comfortably into the 50s” because of the greater structural spend.

How steep is this task? Richardson warns while “the economics are not that easy, the politics are terrifying”.

To grasp how terrifying, Hockey’s 2014 budget that brought such political grief delivered savings from policy decisions of a meagre $36bn over the four years of forward estimates — but this looks like a stroll in the park compared with Richardson’s estimate of above $50bn annually when a future government gets serious.

Where do such savings come from? “This is going to be tough,” Richardson says. “There is no magic wand.” Serious spending cuts will threaten ruin to any future government. What of the tax side? What about taxing the rich? Richardson points out the tax options are limited — the rich are heavily taxed in our income tax system, increasing the GST is a “poisoned well” and hitting the super funds, banks and miners isn’t enough to do the job.

Morrison and Frydenberg have delivered a budget long in the making as Australia has shifted its economic and social priorities — but the price to be paid looms large, even terrifying, and that will constitute an inevitable judgment on the current government.

For the Liberal Party it has been an epic economic transition — from the first Joe Hockey 2014-15 budget enshrined by his “end of entitlement” moralism to the Josh Frydenberg 2021-22 budget defined by the new age of government intervention and spending.