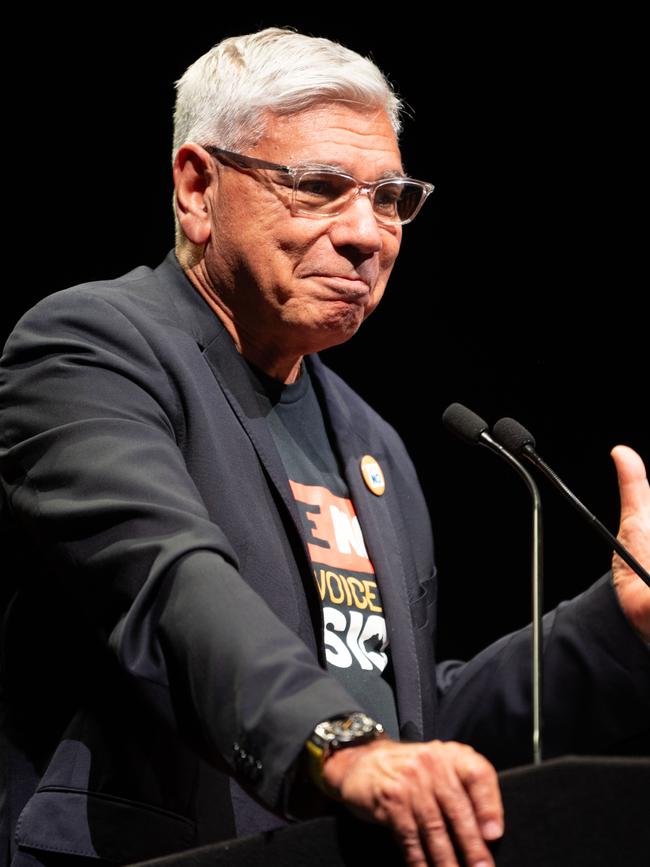

Mundine, in fact, is dead against the voice, treaty, truth demand of the Yes camp because he’s a proud Australian, no less than he’s a proud Aboriginal man.

As well, as the full Uluru Statement from the Heart makes clear, the treaties the Yes camp wants are about multi-billion-dollar compensation claims, not just the Indigenous involvement in land management that Mundine has always supported.

These Indigenous land use agreements, made under the Native Title Act, have been around for three decades and typically involve arrangements between government agencies, such as national parks, and the relevant traditional owners about how land should be managed and what role local Aboriginal people might have in it.

One of Mundine’s main reasons for opposing the voice, in fact, is the demand, contained in the longer Uluru statement, for a Makarrata commission to supplant the traditional owners as the custodians of native title land and the local people who can negotiate about it. In Mundine’s view, this is a push by Aboriginal activists, more familiar with left-wing race theory than Indigenous lore, to shoulder aside those who, by tradition, have the right to speak on behalf of country and its people.

By tradition, for instance, an Arrernte person can’t speak for the Warlpiri or vice versa, so how could a 24-person Canberra voice, or the commission it created, speak on behalf of the multitude of Australia’s first people?

It’s a fair point, but even the Indigenous land use agreements Mundine supports, and that have slowly been under development for years, have extensive potential ramifications for the way we live that only now are starting to become clear.

Take, for instance, the Recognition and Settlement Agreement concluded late last year between the state of Victoria and the Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, representing the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk people of the Wimmera in northwestern Victoria.

These are the descendants of eight named Aboriginal people, born between the 1830s and the 1850s, at the time of the first European settlement. Under the terms of the agreement, “the obtaining … control of our traditional lands, sometimes with extreme violence, (was) instigated through unjust government policy and … occurred unlawfully. This brought rapid and devastating change for our ancestors and the consequences … continue to impact on our people today through intergenerational trauma”.

What’s more, “the State (Victoria) recognises that many of our people were massacred as part of the process of colonisation” and “the dispossession of our people … has had a devastating impact on our health and wellbeing and has prevented wealth from that Country being passed down through the generations”.

Leaving aside the contention surrounding many claimed massacres, and granting that the settlers’ arrival was a seismic shock to the original inhabitants, it’s undeniable that Indigenous life expectancy today, although lower than the average, is still much greater than pre-settlement; also that the wealth of country has been immeasurably enhanced by the improvements that settlers made.

In recognition of the native title that has been granted over hundreds of square kilometres of the Wimmera, the agreement “acknowledges the aspirations of (local Indigenous) people to be sole managers of their lands and waters”. Under the agreement, any land owned by the local BGLC Aboriginal corporation will be exempt from local government rates, plus there’ll be government funding provided for “land management and similar purposes”.

Importantly, the publicly available version of the agreement has redacted the actual amount. There will be a (unspecified) “one-off initial payment” to the BGLC corporation, plus (unspecified) “moneys on trust” paid “to the Victorian Traditional Owners Trust … for and on behalf of the (local Indigenous) people and to be distributed in accordance with the Participation Agreement”. Then there will be unspecified annual payments to the corporation for the next four years for business development and the use of natural resources. After five years there will be a review that, among other things, will consider the “inclusion of timber, gold, silver, metals and minerals operations … for the purpose of the Natural Resource Agreement”.

What all this might mean in practice, and how it will all be funded, is now being considered by the 10 local councils in the area covered by the agreement, including the city of Mildura and the towns of Horsham and Ararat.

Specifically, schedule 6 of the 67-page agreement has a local government engagement strategy that seems to require councils to engage with the BGLC corporation to recommend Indigenous names for “new local roads, bridges and public spaces” and new Indigenous names for “existing roads, bridges and public spaces … with particular priority given to those … that cause hurt or offence” to local Indigenous people.

Fees are to be paid to the Aboriginal corporation for providing this service. Council staff are supposed to receive training in the “lore, customs, languages, spirituality and history” of the local Indigenous people and the Aboriginal corporation is supposed to be involved in all the councils’ strategic planning. As well, the relevant local councils are to “preferentially source goods and services” from local Indigenous businesses and “commit to preferentially employ appropriately skilled” local Indigenous people.

When I recently interviewed the mayor of the West Wimmera Shire Council that is affected by this Andrews government decision, councillor Tim Meyer said they were shocked by what was in the land rights deal and that his council and ratepayers were not even consulted. He was also concerned about new mandatory processes to preference Aboriginal people for council jobs, and Aboriginal businesses for contracts. To think it was only a few years ago that asking people about their race, gender or age was considered discriminatory when hiring new staff, only now, thanks to identity politics, it’s on its way back.

None of this is to be critical of local Indigenous leaders, who obviously are trying to win whatever benefits might potentially accrue to their people under existing law.

And sure, it makes sense for government agencies to work together with local Indigenous people in running parks on native title land. And provided all else is more or less equal, it makes sense to foster more economic opportunity and jobs for Aboriginal people, especially if it helps to bring them out of the backwater of welfare dependency. The issue is how much extra government funding is to be provided under this agreement. And how much all these new consultation and partnership requirements are going to further complicate and delay councils’ decision-making.

Mundine’s fear is that the negotiation of agreements such as this will cease if the voice referendum is carried. My instinct, rather, is that agreements of this kind will become much more common and far-reaching if the referendum passes – albeit, quite possibly, bypassing the traditional owners in favour of activist elites.

Given how many outstanding native title claims there are, reportedly 40,000 in NSW alone; and the numerous, quite complex land use agreements that might have to be negotiated should they be successful, wouldn’t it have been much more sensible to let these measures play out before rushing to a referendum that will entrench even more extensive powers? Certainly, the best way to prevent something like this coming to your town or city is to vote No to a special deal for just some Australians.

The leading No campaigner, Warren Mundine, got himself into trouble last weekend by saying he supported treaties between government agencies and groups of Aboriginal people.