A culture of entitlement had infected the workplace, he said. Post-Covid, “employees feel the employer is extremely lucky to have them”. Tradies and others “have definitely pulled back on productivity”. Having “been paid a lot to do not too much in the last few years”, Australian workers needed to feel the bracing winds of unemployment again.

These rather startling comments attracted international attention, but there was something particularly loud in the home-grown fury.

Perhaps the comments seemed un-Australian, going against a well-established grain: don’t trash-talk the ordinary worker. It sounded ugly in a way that wouldn’t be so in Britain or the US.

Gurner’s frustration has a long pedigree in Australia. It goes back to the first generation of bosses tearing their hair out over slack, idle convicts. Threaten them with the lash as much as you wanted, they just would not do a proper day’s work.

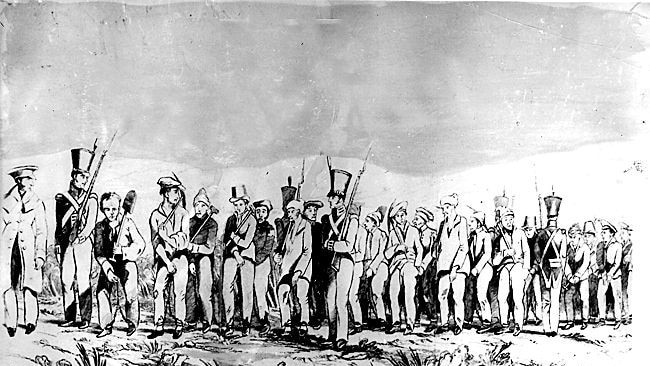

The emphasis on a comfortable life is as old as settlement. Convicts formed the first red-hot labour market, which began to shape the culture of economic life.

If you needed something built, or cut down, or taught to your children, or someone sued in court, or cured of illness, you asked a convict. Early on their overseers, also convicts, replaced the dawn-to-dusk working day with the task system – get the job done, then knock off. The task often was completed by midday and the convict wandered off to their own free time.

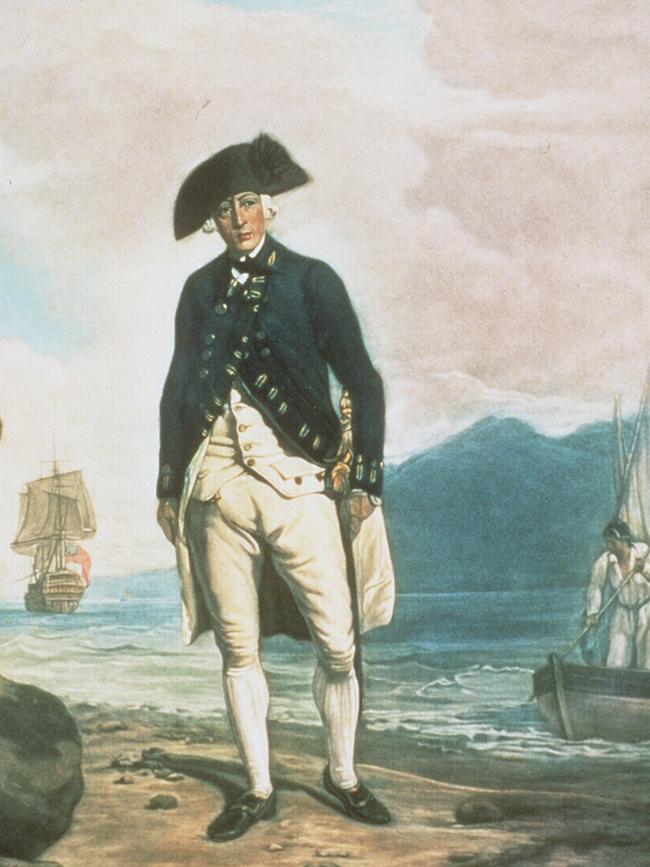

This demand for labour produced the climate that the first Australian-born generations grew up in and took for granted, and it became embedded in the social fabric. Try as latter-day governors and British secretaries and state might, it proved impossible to unwind. Pastoral booms and gold rushes further strengthened the “workingman’s paradise”. It produced a “who cares for you?” attitude among workers that aroused sustained comment among new arrivals. It was a staple of the genre decades before DH Lawrence immortalised it as the opening scene of his 1922 novel Kangaroo, where a cheerful, laconic, overcharging cabbie embodies “My lord the workingman”.

The surliness of Australian shop assistants was legend. Prospective customers, particularly those sporting high-caste airs and graces, were left in no doubt that the retail worker was more than happy to live without their custom. Tipping never took root here, the deference and economic dependence it assumed arousing particularly hostile comment.

It’s entirely typical that one of Australia’s greatest novels of this era, Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life, begins with the exclamation: “Unemployed at last!”

Alongside the “bludging angel”, though, flourished another angel of Australian life – the “battler angel”. This is the upwardly aspiring Australian, looking to make a go of it, improve their lives, set their children and family up for the future. Like the bludging angel, the aspirational angel is evident in convicts making and saving good money from working their trades, setting up shops, building boats, operating ferries.

Convict employers quickly found that the brutal approach – exemplary flogging – was worse than useless in procuring more productive workers. Instead the shift to task work gave incentive to convicts to get the assigned work done and then pursue their free time as they saw fit. Many simply drank, or gambled, but still others used their time productively. They tended their own crops, pursued trades and worked for good wages.

Gold rush diggers on their own or working together with a few mates continued the tradition: having a go, trying to make enough of a fortune to realise the sustaining dream of personal independence, security and prosperity.

Whether building farms and businesses, working overtime or owning houses, the trait was evident across all classes and walks of life, a defining Australian ethic embedded in the land of the long weekend.

These two angels are not warring types or classes. Mostly they inhabit the same person at different stages of life. Both angels are by-products of the politics of abundance, which suggests the problem with Gurner’s hopes for the constructive effect of an economic crash.

If Australia’s track record is any indication, economic crises and sudden surges in unemployment have been as counter-productive as flogging convicts to make good workers. Crashes have doused rather than inflamed the animal spirits of economic striving, healthy ambition and entrepreneurial vim.

The classic example of this is the 1890s Depression. Yes, unions were destroyed, broken in a series of monumental strikes that crippled the nation’s economic and daily life, and workers forced to accept slashed wages. But the losers then were soon to win, and win big.

Arbitration and centralised wage fixing were the political solution for the economic debacle – judges in wigs deciding what the standard wages would be. This, along with constantly rising tariffs, became the Australian Settlement, unchallenged until the 1980s and ’90s: about as long a policy hangover as you could wish for.

The one real exception to this rule would seem to be the great reform era that dismantled the Australian Settlement – the Hawke-Keating-Howard-Costello years. Yet this too carries salutary caution. From the 1973 oil shock to the “recession we had to have” were nearly two decades featuring strikes, rampant inflation and shocking unemployment levels.

Unemployment blights lives, whole lives, and often successive generations. In this case, too, the efficacy of brute economic pain is questionable. We need another way.

The other way has to speak the politics of abundance, to better persuade that better angel perched on all our shoulders.

Rather than filling in time waiting for the next economic cataclysm, it would be far better to create policies that provide incentive for the perennially aspiring battler Aussie. A return to enterprise bargaining would help. More readily available land and better zoning laws for cheaper housing also. An education system that can reverse rather than accelerate the alarming slide of basic literacy and numeracy among school students most of all.

This sort of common sense worked for the first generation. There’s no reason it couldn’t now as well.

Alex McDermott is a freelance historian.

It’s not every day you hear a grown man ask for more “pain in the economy”, as property developer Tim Gurner did last week.