Misinformation laws put at risk the very freedoms we take for granted

This example illustrates the problem with the so-called combating misinformation and disinformation legislation that has been introduced into the federal parliament. It targets contestable political opinions on social media and is based on the patronising assumption that members of the community cannot make a judgment about those opinions but must be protected from the obvious inadequacies of their judgment.

The legislation allows the Australian Communications and Media Authority, by means of an elaborate system of codes and directions, to supervise the content of social media bodies such as Google, Facebook and X, and encourages complaints about that content to be made by those who disagree with it.

Both misinformation and disinformation, the latter involving “grounds to suspect” an intention to deceive, are defined to contain material that is “reasonably verifiable as false, misleading or deceptive” and is “reasonably likely to cause or contribute to serious harm”. All these concepts have a wide scope for subjective judgment and, when combined, could lead to the exclusion of many arguable opinions on social and political questions.

Who decides if there are grounds to suspect there is an intention to deceive? What is the test for assessing if a statement is reasonably verifiable as false, misleading or deceptive? As to serious harm, among the categories provided by the legislation are such nebulous notions as the vilification of various groups in Australian society, imminent harm to the Australian economy, and harm to the integrity of a federal, state or local government election. This last case would open up to complaints the claims of politicians at all these levels of government in the course of election campaigns.

Even before any intervention by ACMA, however, social media bodies would be forced to initially consider questions of falsity and serious harm when confronted by a complaint about material posted on their systems. This obligation would inevitably lead to the suppression of many political opinions, given that the safest course for those bodies in response to a complaint would be simply to take down the material in dispute without analysing its content and so avoid any possible action by ACMA later on.

The view that most people need to be protected from themselves is nothing new. In his 2012 report, which was commissioned by the Gillard government and recommended the establishment of a government body to control the news media, Ray Finkelstein KC said “even armed with full information, people do not necessarily have the means for weighing and evaluating that information”. And as to the capacity of citizens to engage in critical reasoning, there is “real doubt as to whether these capacities are present for all, or even most, citizens”. In other words, most members of the community cannot be trusted to reject an outlandish statement on social and economic issues so they must not be exposed to public debate on such questions.

No doubt some of the statements made on social media stretch credulity but, as American jurist William O. Douglas said in the early 1950s: “When ideas compete in the market for acceptance, full and free discussion exposes the false and they gain few adherents.” To similar effect, another American jurist, Oliver Wendell Holmes, said in a judgment of the US Supreme Court in 1919: “The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” It might be thought that Australians have generally had a history of scepticism for political views and that the optimism of Douglas and Holmes would be borne out in most cases.

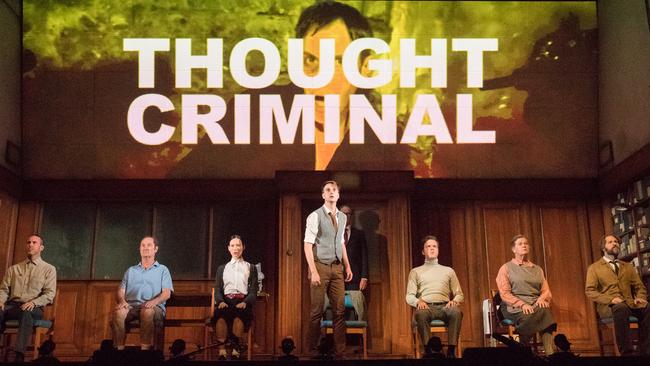

References to Orwell’s 1984 have become something of a cliche over the years but there is a sinister suggestion of its thesis in proposed legislation that is designed to sanitise public debate on a range of political issues so any debate that does occur accords with the views of a group of government-appointed bureaucrats.

Michael Sexton’s latest book is Dissenting Opinions

Consider the statement that federal government expenditure has contributed to inflation in Australia. Could this be misinformation or disinformation? And who decides on the answer to this question. Certainly not a panel of professional economists who could be guaranteed to disagree among themselves!