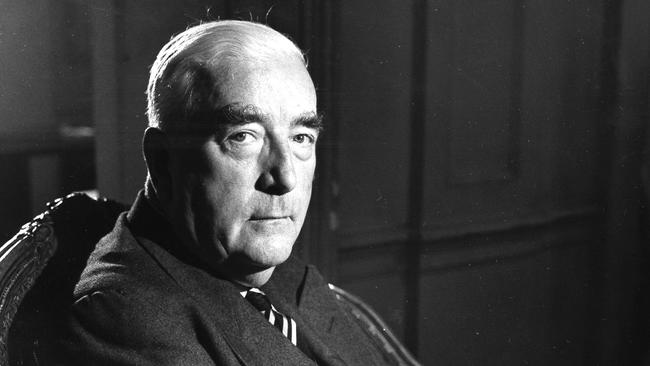

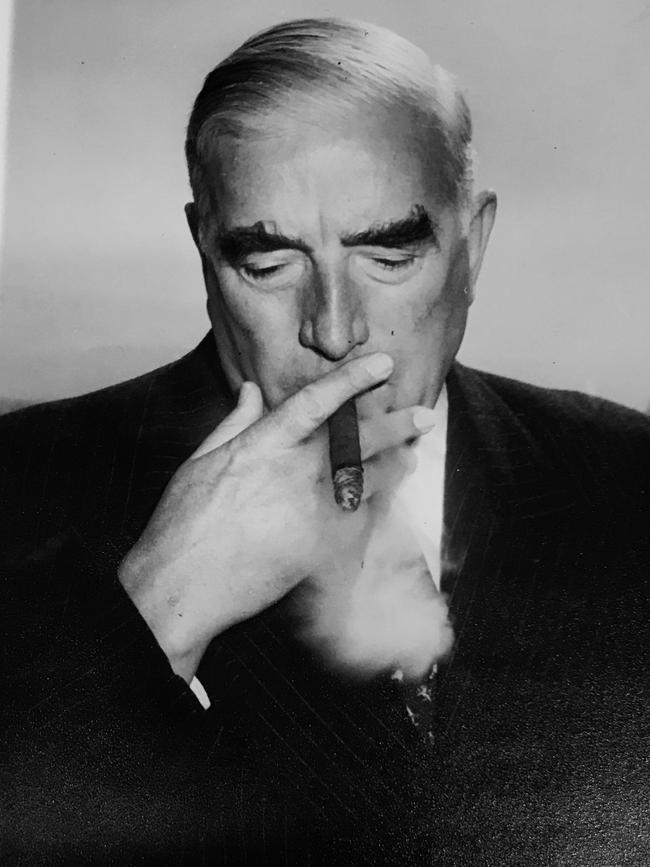

Menzies still a beacon for our troubled age

But close observers of this Menzies-palooza will notice that certain topics have tended to be dismissed as no longer having relevance. Foremost among these have been Robert Menzies’ views on trade and immigration.

This is odd as these issues are inherently important and have become especially so in recent years. They were the driving forces for the surprising Brexit result and Donald Trump’s 2016 US presidential victory, and have been credited with allowing centre-right parties to gain improbable victories in the Labour “red wall” in northern England and in long-held Democrat states in the industrial American mid-west.

It is also clear that Menzies would have been on the side of these Forgotten People and their rebellion against open-borders trade and immigration policy. On trade he was admirably direct, albeit at odds with contemporary Liberal Party representatives. “I am a protectionist,” he declared. “I don’t think that the history of Australia could have been what it has been without the great industrial enterprises, the great basic industries, the great factories of Australia. I am not saying something clever when I say that I am saying something quite obvious.”

Menzies was not, as some suggest, uninterested in economics. He lived through the Depression and his family knew the even worse downturn of the 1890s.

A well-educated Presbyterian Scot, he was also well aware of the academic theories of Adam Smith and others. But he knew, far better perhaps than any who sit in parliament today, about the realities of trade and geopolitics. Like many other great men before him who knew how to create and kept nations together – George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, and Canada’s John A MacDonald – Menzies knew about the importance of protectionist tariffs. He grasped the essential role they played in building and sustaining a manufacturing base, creating a middle class and ensuring a nation’s independence.

In Australia, almost all manufactured goods from China arrive without any tariff imposed. With breathtaking incoherence we levy green taxes on Australian businesses to supposedly cool the planet yet allow solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and the like to be imported from polluting Chinese factories via diesel-powered ship, duty free. We allow Beijing-controlled tech companies to operate here in a way Western tech companies cannot in China.

All this makes zero strategic, commercial, or ecological sense, yet this arrangement somehow enjoys bipartisan support in Canberra today. Menzies would have thought it bonkers.

Menzies’ views on immigration, properly understood, also have much to say to our age. There is no point denying the fact during his time he was in favour only of immigrants to Australia of European stock. We have been conditioned to feel ashamed of these earlier immigration policies, but they were no stricter than those of most countries in our region today. Japan, a developed, well-ordered country and our friend, is not considered an international pariah for maintaining a policy similar to the one Menzies advocated.

It is also clear Menzies believed in this immigration policy, not because of any animus towards those from other parts of the world but because he thought it important for establishing a cohesive community. It was in no small part because of this focus that intractable ethnic conflicts were practically unknown in Australia and our minorities were, all in all, better protected than almost anywhere.

Australia was one of safest places to be a Jew in the 20th Century, whereas over the same period the more diverse regions of multicultural Europe and elsewhere witnessed the horrors of forced population transfers, pogroms, and concentration camps.

Today most of us have beautiful friends and family, who we know and love, who come from different backgrounds and who have become proud Australians. Clearly at some level Menzies underestimated the capacity that Australia would eventually have for incorporating people from different walks of life. But this later success was only possible in no small part due to the existing cohesive society that earlier stricter policies built.

Immigration policy in Australia and across the Western world has been conducted with far less prudence in recent times. Consistently high levels, including the insane net 400,000 increase under the Albanese government number last year, have never had a proper democratic mandate.

They have reduced the capacity of young Australians to get into the property market and form families. They have reduced wages and put huge strains on public services. They strain the social fabric by culturally transforming suburbs against the wishes of locals. They have provoked an understandable political backlash.

There is no reason these numbers should not be drastically reduced and for some time. We need to prioritise our own young people. Similar to trade policy, the focus should return to making it easier to produce things here ourselves – in this case babies and new families – rather than simply thinking we can import what we need from overseas without consequence.

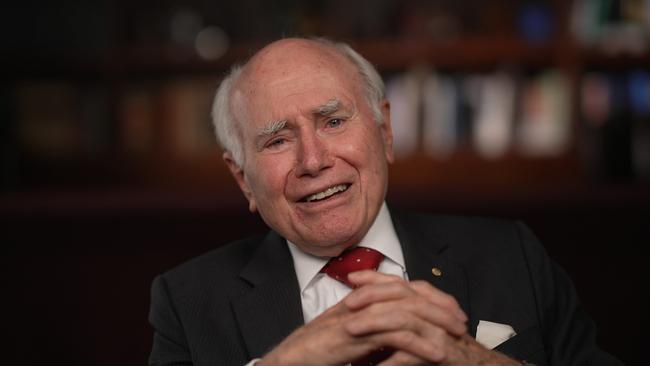

There has been a tendency by some, such as George Brandis, to invest too much in the term Liberal in the name of the party Menzies founded. They want to suggest he intended to govern according to the purist classical liberal philosophy of the late 19th century.

Yet the first party Menzies ever joined was called the Nationalist Party. Politically as well as philosophically, it is truer to say Menzies was nationalist first and a liberal second.

When Menzies came of political age the British Liberal Party (not unlike the Australian Liberal Party of today) was a politically spent force – clinging to policies which may have been appropriate a generation or two ago but were no longer. Menzies did not seek to replicate it.

Yes, Menzies was a lover of freedom. Without doubt, he would have been repulsed by the tyrannical pandemic restrictions promoted by the current holder of his federal seat, Monique Ryan, and the incumbent Premier of his beloved Victoria, Daniel Andrews. It is also true that Menzies’ nationalism was an enlightened, broad-minded variety, not a reactionary sort. But he knew abstract liberty-loving principles always needed to be reconciled with the national interest, and that was never more the case than when it came to immigration and trade policy.

For those who wish to learn from Menzies, these are among the key areas that need to be reassessed if one seeks both to positively reshape Australia and to replicate his electoral success in the 21st century.

Dan Ryan has held senior positions in the Liberal National Party in Queensland. He is the director of the Australian Institute for Progress.

Since the publication of John Howard’s The Menzies Era almost a decade ago, there has been an unexpected revival of interest in Australia’s longest-serving prime minister. Copious podcasts, dinner speeches and research papers have been produced. Liberal Party grandees have fallen over themselves to profess how much they embody his values.