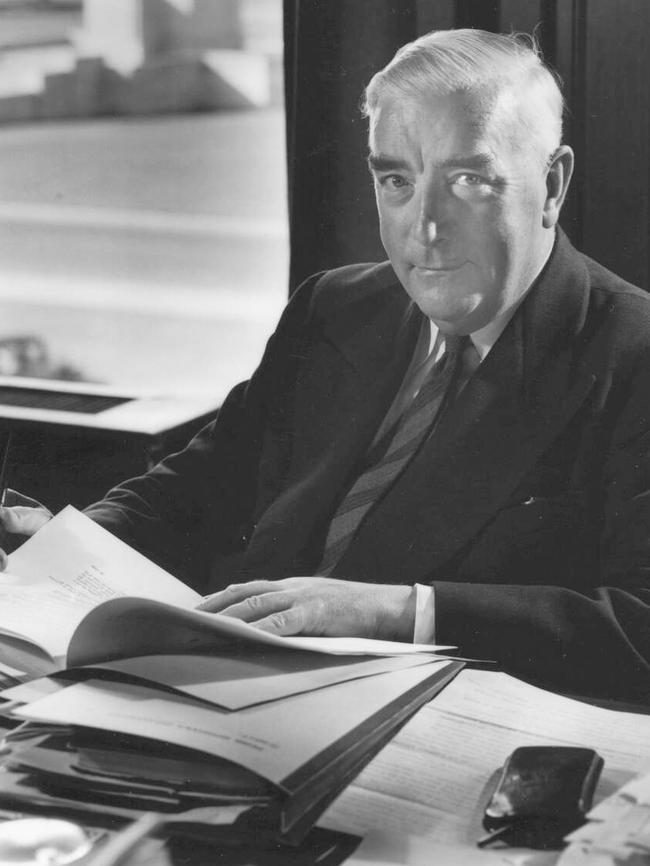

Robert Menzies, the shy statesman

A private secretary to both the former PM and the Queen remembers the founder of the Liberal Party on its 75th anniversary.

If it is true that no man can be a hero to his valet, it must be the case that a great man’s private secretary — particularly when that great man is prepared to admit the private secretary into his domestic life on intimate terms — must know him pretty well. The more remarkable, then, if that great man remains a hero to the private secretary. And Sir Robert Menzies undoubtedly remains a hero to me. So it is worthwhile to put down some of my lasting memories of the former prime minister as his private secretary from 1955 to 1959.

What sort of a man was he? In a 1999 speech, David Flint, then chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Authority, said the media almost only ever recalled him through the prism of the unfortunate “I did but see her passing by” speech, or in the uniform of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. This was contested by other commentators, but I know what he meant. There was certainly a disposition to depict him in the light of lickspittle of the monarchy and as if being “British to the boot heels”, as he had described himself, meant he was something less than an ardently patriotic Australian. As I saw him, nothing could be further from the truth in either respect.

Extreme probity

His Presbyterian upbringing had left an indelible mark on RGM. His language was always proper, and swear words, even the milder ones, never passed his lips. What a contrast to the foul language that seems to have become the normal currency of politics.

Not only in language was this Presbyterian upbringing reflected. Menzies’ whole approach to public life was one of the most extreme probity. Nothing was allowed that might be thought to be for his personal benefit. To take but one example, the RAAF VIP Squadron, which had been set up in Canberra, was used by Menzies only on those occasions when he could claim without any shade of doubt to be travelling on official business. A private weekend in Melbourne, or a weekend with engagements of a slightly political flavour, and we would be up at some unearthly hour of the morning to catch the ANA or TAA milk run (commercial flight) to Melbourne, always with a stop at Corowa on that first flight of the day.

Another good example of his reluctance to authorise any expenditure on himself was the state of the furnishings in the PM’s office at Parliament House. The original carpets and curtains from 1927 were still in place in the 1950s. It was only when the curtains began, literally, to hang in shreds that he could be persuaded to have new ones hung. Then, typically, the job was undertaken by some “little women” from Melbourne who were known to his wife, Dame Pattie, for their reputation for doing such work economically. These high standards were imposed on all his ministry, and there can have been few administrations anywhere in the world so untainted by any hint of corruption. Self-interest, or the taking advantage of official position for self-benefit, would not have been tolerated.

Earning trust

One small incident of my early days as private secretary may illuminate the man, and my relations with him. He was by nature antipathetic to change, and it took him some time to adjust to the idea of a new private secretary. His own essential shyness contributed too to his wariness with a new man in the office. His background in the conservative workplace of the Melbourne bar led him to address all those male acquaintance who were not intimates by surname only. This came as less of a shock to me, accustomed as I was from school and university to this form of address, than it might to someone in a similar situation today.

Nonetheless, it galled slightly that he called me “Heselteen”, when the family had always pronounced the name to rhyme with “dine”. Occasionally I would clear my throat and venture a correction. The response was always the same: “You don’t know how to pronounce your own name, laddie.”

One day as the two of us drove together in the prime ministerial car in Melbourne, we went through this routine. I riposted by saying this observation came well from someone whose name was “Mingies”, and who went masquerading round the country as “Menzies”. “Humph,” he said, hating as always to admit he might be wrong about anything, “I suppose that it’s about time I started to call you Bill.” From that time our relationship seemed, to me at least, to be on a different footing.

‘Basically indolent’

By the late 1950s, it was evident he had seized the importance of cementing Australia’s relations with Asian neighbours, even if this meant that his own instinctive urge to find Australia’s place in the world alongside the old Anglo-Saxon allies had to be deliberately refined.

He was as much the artful and skilled politician as world statesman, and it was fascinating to see these two sometimes contradictory urges competing for precedence in his actions.

He had the habits of a lawyer — late starts in the morning and later nights, the ability to master in a short time a complicated brief — and also the weaknesses of the lawyer. There was a tendency to think that once he had made a powerful speech on some topic in parliament, his job was done, and he did not always follow through as a different type of politician might have done.

He had a wonderful capacity for taking in the whole contents of a page of typescript at a glance, and of noticing any minor grammatical or other errors in any paper put before him for signature.

He described himself as “basically indolent”, and there was, I think, a grain of truth in this. Some major decisions got put off while he let the topic simmer in his mind, (for example, the question of amalgamating the Canberra University College with the ANU), but in lesser matters, he seemed to prefer to put off to the morrow some things that might better have been done on the day.

If an important speech had to be written, that too usually got put off until the last possible moment.

His reputation for genius in matters of political timing was, I sometimes thought, more a matter of putting things off until they could be put off no longer — perhaps the same thing!

His ability to take the political atmosphere, certainly in the lobbies and party rooms of Parliament House, amounted to genius. A walk through the lobbies, (though not something he felt he needed to do very often) enabled him to take in through his pores all the current political intelligence.

He absorbed in some extraordinary way all that he needed to know about whatever was going on at the time.

This is a mark of the consummate politician, always to be ahead of any development that might impinge on political life, and Menzies had it in full measure. Between elections, there were occasional “meet the people” tours of the farther flung parts of the country. Unlike the prime ministers of the 21st century, however, by far the greater part of his time was spent in the office — not out and about creating “photo opportunities”.

He was often depicted as arrogant. I would never have described him thus, but vain, about his intellectual achievements, yes, certainly. And to some extent about his appearance. He would never appear in public without a jacket, and nor in public did he care to use glasses for reading.

Reading and drinking

He had a wonderfully retentive memory, not just for the necessary political activities of the period, but also for the literature he had absorbed in his youth. He was usually able to come up with an apt quotation, and liked to show off his familiarity with the classics in art and literature, likewise his knowledge of wine. But he showed little inclination to keep up with, or sympathy for, more contemporary poetry, literature or art. His reading for relaxation was mostly of whodunits, brought from the Parliamentary Library by the armful, and selected on his behalf by someone else.

He enjoyed the exercise of power and patronage, and was a man of vigorous appetite for food and drink. His staple pre-lunch or dinner drink was the dry martini, and whisky was what he needed at the end of the day or when winding down after an important speech or other intellectual effort. His knowledge of wine was considerable, aided by his capacious memory, but in food he appeared to have little of the connoisseur’s interest. His favourite dish was Irish stew or sausages. He liked nothing but the mildest of cheddar cheeses. He got through a good number of cigars each day; for everyday smoking they were the Australian-made product of British Tobacco, but havanas for a special occasion.

Shy leader

Many people have been surprised to hear me describe him as shy, but I think it is true that he was by nature more introvert than otherwise, except with old friends, or in the company of lawyers and politicians. Even these latter were not always congenial. He was always able to put aside his sensitivities about hurting people when it was a matter of political point scoring, but he was very far from happy if he had to confront anyone face to face with hurtful decisions. Cabinet reshuffles were always a painful time. To his discredit, this sometimes had the effect of making him criticise someone to a third party, instead of directly. He hated making a fuss about things in public.

Against his reputation for arrogance, intellectual arrogance at least, and coldness, I was more struck by his genuine kindness and consideration for some of the lowlier members of his personal staff. Buzz Kennedy has recorded in his book the occasion on which he entertained his Melbourne driver, Peter Pearson, to lunch at the Windsor, and the surprise of other diners on learning the identity of the guest. Menzies himself would certainly have seen nothing inappropriate in the notion.

He was equally nice to Wally Dunn, about whose personal appearance and care for his car, which the Menzies grandchildren all thought was Wally’s car, the PM was inclined to be critical — to others. When Wally was awarded the BEM, (a medal that was not presented at a formal investiture at Government House), RGM decided on a special ceremony at The Lodge. On a Saturday morning in October 1959, in the presence of all his family, Wally’s BEM was personally presented by the prime minister.

In my own case, I felt it was some time before I was accepted. Partly this was simply because he did not much care for changes in his routine or office, but it was also because he didn’t make friends easily. His manners were formal to an extent that was already becoming old-fashioned in the 1950s.

It was probably because he was something of an introvert that the extroverts like Atholl Townley, Hughie Dash and Jim Scholtens made such an appeal. He saw in them a quality that he knew he lacked, and possibly envied.

In Melbourne I had continuing opportunity to see him as a family man. He was wont to say of himself, in jest, that he had married above himself. Certainly Dame Pat was an enormous political help to him, with that ease of contact with every man that he himself lacked. Parental pride centred on his daughter, Heather. She has repaid that love and pride most amply as the guardian of the flame since his death. To all his grandchildren, he was a devoted and doting grandfather.

Cutting wit

Of his flashing sense of humour much has been written, but the written record can never do full justice to the wit of a man whose shafts were nearly always impromptu, neatly judged for their audience and the moment.

I recorded a few of his aphorisms, and one or two of these say a good deal about the man and the way he worked and thought. I particularly remember the gibe directed at the Labor Party in the year of the great split, 1955. In the December election campaign, at one of the early meetings, he referred to the Labor Party, then, with exquisite timing, a pause, and “or, what is loosely called the Labor Party!”

In April 1958, I was setting up a meeting over some matter that I have long forgotten, and he said he would meet the lawyer concerned at his chambers in Sydney. “Is that proper?” I queried. “Shouldn’t you stand on your dignity, and invite him to come to see you in your office in Canberra?”

“Laddie,” he replied, “a person who always stands on his dignity, ends up by trampling it under foot!”

I remembered this dictum many years later when dealing with a very touchy prime minister of Western Samoa, Tu’upuola Efi. I quoted it to him, and it had a most beneficial effect on our negotiation.

Renowned for his own dislike of the press, the PM defined the conflict between the press and parliament for me at a Kirribilli House stay in September 1959, as “the classical conflict between the self-appointed and illiterate and the elected and semi-literate”.

Legacy

When asked to summarise Menzies’ achievements as PM, as I have sometimes been, it is not so easy to point to one or two landmark political decisions. I have usually said his two great contributions, at least in my time, were to bring an atmosphere of total probity into the political world of Canberra, and to win for Australia and Australians a new reputation and status overseas, where his reputation stood so high.

He himself would probably have put high on the list his contribution to education in Australia, in the tertiary field primarily, but also for the brave decision to provide commonwealth aid to denominational schools. Certainly he had a genuine passion for academic freedom and was a true friend to the ANU, even if he had little time for the views of some of its social scientists. While outside my own experience of the man, many people would rate his fight back to office, and his construction of the Liberal Party as his highest achievements. It was a task on which he lavished all his great powers, his energy and determination.

While he hugely enjoyed recounting the story of the removal man who asked him, when unloading his possessions into The Lodge in 1949, whether this was really worthwhile, as his stay was to be such a short one, I don’t think he would have expected that stay to be a record-breaking one.

One mark of his greatness, I have always thought, was his ability to see when the moment had come for him to leave office, and to stay clear of Canberra and its political manoeuvres after he had gone. He left politics a poorer man by far than when he made the move to the federal parliament, and I doubt that this has been true of any minister of the crown, let alone prime minister, since his retirement, (and not too many before him either). He made no move to capitalise on his status after he had retired, again a highly unusual state of affairs in today’s world of politics.

My work in the private office was done in an era when politicians still did an amazing amount of their own work, in Menzies’ case including writing all his own important speeches. This meant that private offices were small. The PM’s office consisted of nine persons, including two messengers, and other offices were even smaller. The corps of private secretaries was almost wholly male, although there were some faithful female personal secretaries like Hazel Craig in the PM’s, and in other offices as well. This reflected the parliament of that era as well, where women were in a tiny minority.

When I left his office, I asked if he would be kind enough to sign a photograph for me. It is affectionately dedicated “To my old slave”.

Sir William Heseltine was private secretary to prime minister Robert Menzies from 1955 to 1959 and performed the same role for Queen Elizabeth from 1986 to 1990

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout