Major parties must support reform for nation’s sake

Labor and Coalition supporters alike are now shaking in their boots, as are the parties of government. Of course, the minor parties have the champagne on ice, relishing the chance to hold the country to ransom. The Greens are salivating.

In 2010 independent MP Rob Oakeshott predicted the 43rd parliament would be “beautiful in its ugliness”. He was wrong; it was just ugly. As the chief government whip at the time, I feel well qualified to pass that judgment.

But must every hung parliament be ugly?

The answer, of course, is no. Indeed, no must be the answer because hung parliaments may become the new normal.

When Bob Hawke won the 1983 election the major parties shared 90 per cent of the primary vote. That number has been declining ever since, falling to just 68 per cent at the 2022 election.

Given the growth in minor party and independent candidates, that number could fall even further at the 2025 election.

Safe seats are now rare, too. At the last election just 15 successful candidates won without relying on preferences.

The biggest barrier to a healthy and productive hung parliament is culture. Unlike our European friends, power-sharing is not in our DNA. Our system is hyper-partisan, arguably more so than is the case in our mother parliament in Westminster.

In Australia’s last hung parliament, members of the government began each day unsure we’d still be the government by nightfall. Every parliamentary sitting day provided the opposition with an opportunity to become the government or to force an early election. Of course, opposition MPs behaved accordingly.

The shrinking vote of the traditional parties and the reduction in the number of safe seats have another consequence. Meaningful policy reform is becoming more politically dangerous and difficult. Could Hawke and Paul Keating progress their economic reforms in our current political environment? I suspect not. Could John Howard win an election promising a GST? I doubt it.

Reform has slowed and the culprit is not a lack of political courage, it’s the reality of our modern parliamentary democracy. The electorate has changed dramatically, yet our parliamentary processes, culture and behaviour have hardly changed at all – they now need to. Changing parliamentary culture and architecture will take time. But if the next parliament is hung an earlier and faster opportunity could present itself; a chance for some very real policy reform focused on lifting Australia’s ailing productivity and bolstering economic growth.

The next election will deliver one of four obvious possibilities: a Labor majority, a Coalition majority, a Labor minority government or a minority Coalition government. But the fifth possibility is a deadlock and a second election. An election re-run would be without precedent but, hey, the world is changing in significant ways. The 2010 election outcome was made more complicated by the 72-all result.

There is a strong argument that if both the major parties fail to secure a majority at the next election, the party leader with the greater number of seats should be supported to form a government.

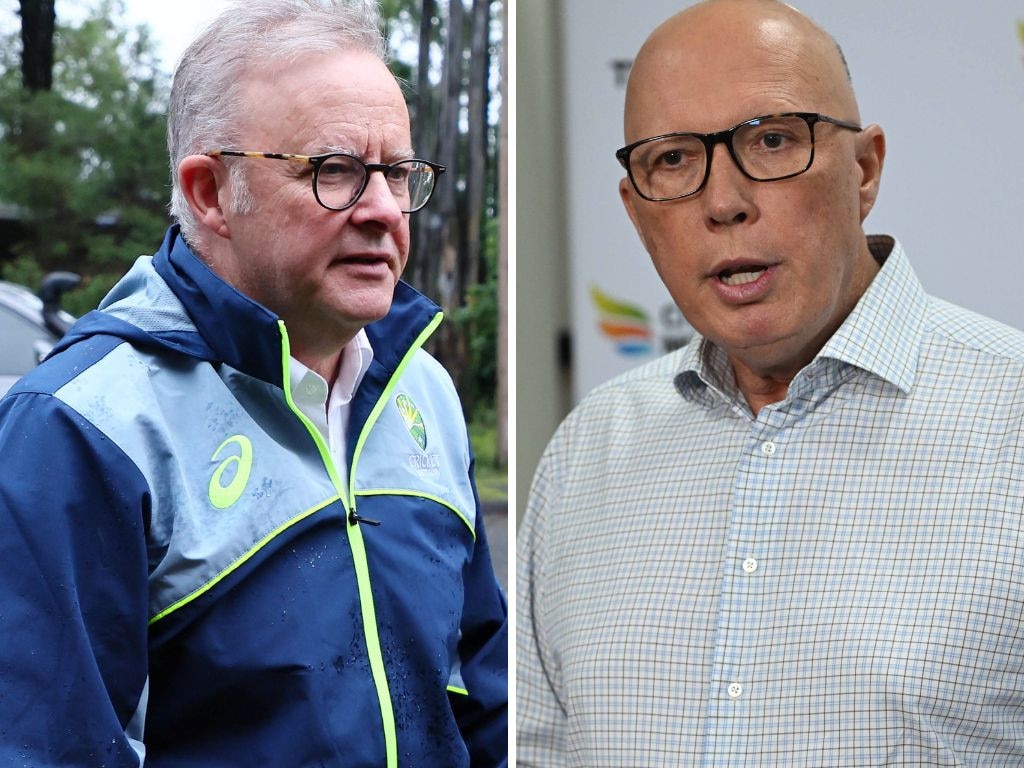

Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton may soon be given the opportunity to seriously revive the economic reform agenda by agreeing – before the election – that whoever has the most seats post-election will be guaranteed both supply and confidence for 18 months hence. Further, each major party will support an agreed economic and regulatory reform package.

They should further agree that the reform package will be drafted by a roundtable of relevant stakeholders, including the major parties, premiers and representatives from industry and community sector peak bodies and the trade union movement.

Tax reform, including state taxes such as payroll and regulatory burden, should be agenda items one and two.

People on both sides of the political aisle may say I’m blaspheming. “Never give a mug an even break,” they may say. “Why would we deny ourselves an opportunity to build a disparate coalition and three years in government?”

Fair questions. But the answer is simple: it would be good for Australia, a rare reform opportunity in a changing and challenging world. The arrangement could extend to the Senate, a chamber that is almost always hung. It’s a much better option than an investment-chilling dysfunctional parliament or an expensive election re-run.

Our strategic guidance demands we invest even more in our defence capability than is currently proposed, and we must. But where will the money come from? More public debt is not an option and budget saving opportunities are very real but limited.

What we need is a significant and ongoing efficiency and growth dividend.

Ironically, a hung parliament may provide our best chance of securing one.

Joel Fitzgibbon is a former defence minister and chief whip during the Gillard government, 2010-13.

If the pundits and pollsters are right, we’re headed for another hung parliament, one in which neither of the major parties enjoys a majority.