The prevailing theory goes that if the universe was random, half of its galaxies would rotate clockwise with the other half rotating counter-clockwise, but an associate professor of computer science at Kansas State University, Lior Shamir, examined 263 galaxies and discovered that two-thirds rotate clockwise with the one-third remainder rotating counter-clockwise.

“It is still not clear what causes this to happen,” Shamir, a member of the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey known as JADES, told the Kansas State University news website, K State News, on March 12.

“One explanation is that the universe was born rotating. That explanation agrees with theories such as black hole cosmology, which postulates that the entire universe is the interior of a black hole. But if the universe was indeed born rotating it means that the existing theories about the cosmos are incomplete.”

Black hole cosmology is the theory developed by physicist Raj Kumar Pathria and his planet-sized brain, who as an expert in thermodynamics, statistical mechanics and mathematical physics, took up research on relativity almost as a hobby, like one might take a crack at lawnmower repairs. Pathria theorised that our universe has been subsumed by a black hole and that it is part of a parent universe or indeed, multiple universes that sit outside the black hole and who presumably have a fleet of astrophysicists on an obscure little planet in their Daddy Universe, staring into their space telescopes exclaiming: “Have a look at the size of that black hole.”

As we all know, space is really big and dark. Astrophysicists tend not to agree on much but there is general recognition that around 14 billion years ago on an otherwise uneventful Thursday, our universe was created with an impressive pyrotechnical display. No one seems to know what was going on beforehand amid general babbling on gravitational singularity. Did some god-like power light the wick on it? No one knows. Now with this slight nudge towards black hole cosmology, it would appear there may be other universes. When they were created and how also remains in the deep unknown.

At face value, it changes everything at a less lofty intellectual level. Any employee with a gleam in his or her eye, looking for an excuse for a sickie will never find a better one. “Can’t come in today. Stuck in a black hole. It’s playing merry hell with the space-time continuum. Also the train drivers are on strike again.”

Are we now, according to the stories our more lurid science teachers used to regale us with, housing our own universes on our persons, sort of cosmic matryoshkas dolls going all the way to the sub-atomic level? Should I fret for the micro universes wedged in my armpits? Well, probably not and maybe put the bong down and turn off Dark Side of the Moon.

Nevertheless, Lior Shamir’s investigations, in a study authored solely by him and now available for peer review, raises important questions. If our universe is one enormous black hole, why are there other black holes along for the ride in here with us? The theory, again more theory, goes that the black holes inside the black hole we call home might actually be Einstein-Rosen bridges or worm holes – theoretical short cuts through time.

Could we simply stick a toe into a wormhole and go back in time to, if my knowledge of bad movie premises is anything to go by, Victorian England and the hunt for Jack the Ripper, possibly via a magical hot tub? It’s possible. It could be a boon for True Crime podcasts. Personally, I’m not expecting too much. If I could just somehow scramble back to the 1980s, I would save a fortune in wardrobe and hair cuts. That will always be the dream. Alas, the laws of physics reveal we can conceivably travel forward in time but not backwards.

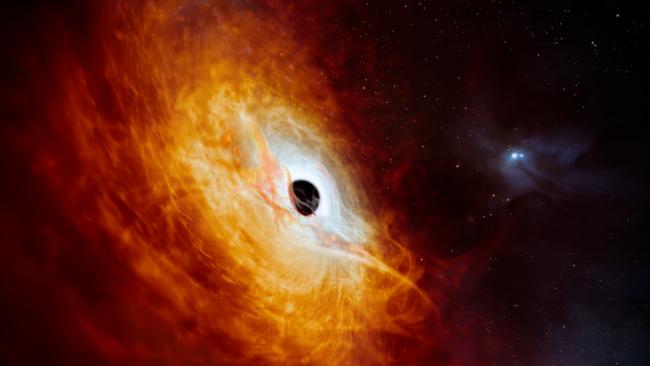

That is, in wandering into a wormhole we might transcend time where a mere blink of the eye is a weekend anywhere except Adelaide where it will obviously feel longer. We don’t know a great deal about black holes and until very recently, evidence of their existence lived in the theoretical. Viewed through the $10n James Webb Space Telescope, they come across as just darker patches of deep space. Before that, there were only artists’ impressions.

As an editor of a magazine of ill-repute many years ago, we were doing a rare story on astronomy. I asked one of the artists on staff for “Six black holes by four o’clock.” Or was it four by six o’clock? The artist returned with some sketches that I sniffed at. “You call these black holes?” In the end, the page featured an image of a sinister looking vacuum cleaner which was probably closer to the mark.

Visual concepts aside, what we do know about black holes is that they are so dense, they could run as candidates for the Trumpet of Patriots.

At the same time, they are all but invisible and incapable of emitting light which sounds more like the Victorian Socialists. But the great unanswered question is how can we exist in a black hole with gravitational forces that should render us all into a fine pink mist while crushing Earth like a can of XXXX in a thirsty man’s hand?

We are mere specks of dust taking up a tiny space in a violent, ever-changing cosmos, the scope and size of which is beyond normal human comprehension, especially if you’re in Adelaide.

A recent study using the James Webb Space Telescope has promoted the theory long held by certain astrophysicists that we live in a black hole. This goes a long way to explaining Adelaide. Although, if one stood on the edge of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole currently chewing its way through the centre of the Milky Way, 700 years would feel like a minute which doesn’t sound like Adelaide at all. If anything, it would be the reverse.