Liberals ditch proud history of Indigenous advocacy

The Liberal Party took Australians to the polls in 1967 to remove discriminatory references to Indigenous peoples from the Constitution and in the years since its leaders have committed to further reform. Former prime minster Tony Abbott even remarked he would “sweat blood” to secure the recognition of Indigenous peoples in the Constitution.

This makes it all the more disappointing that the party will lead the charge against a constitutional change developed by Indigenous people with support from senior conservative figures.

One remarkable feature of the Liberal Party’s decision is that it has been taken so early. The government has released its proposed wording, but parliament has yet to have the final say on what is put to the people. This will be resolved in coming weeks with the aid of a cross-party committee that will examine the wording and hear from the community. Coalition members have rightly talked up the value of the parliamentary process.

Liberal MP Keith Wolahan, as deputy chair of the committee, said it could act as a “constitutional convention”. He and others have recognised how important it is that the government’s wording is subjected to scrutiny and debate. It makes it all the more surprising that the Liberal Party has pre-empted the process and made its decision without hearing from the cross-party committee and community.

The process will provide opportunities for challenging the government and suggesting amendments. There was no need for the Liberal Party to make a hasty call now.

The Liberal Party has also seemingly forfeited the option of pressing its own amendments. One sticking point has been the government’s proposal that the voice make representations to the executive. This no doubt will be a focus of the committee’s work, and opposition members might move an amendment to the government’s bill that the word “executive” be deleted. The Liberal Party might even have presented this as the price of bipartisanship.

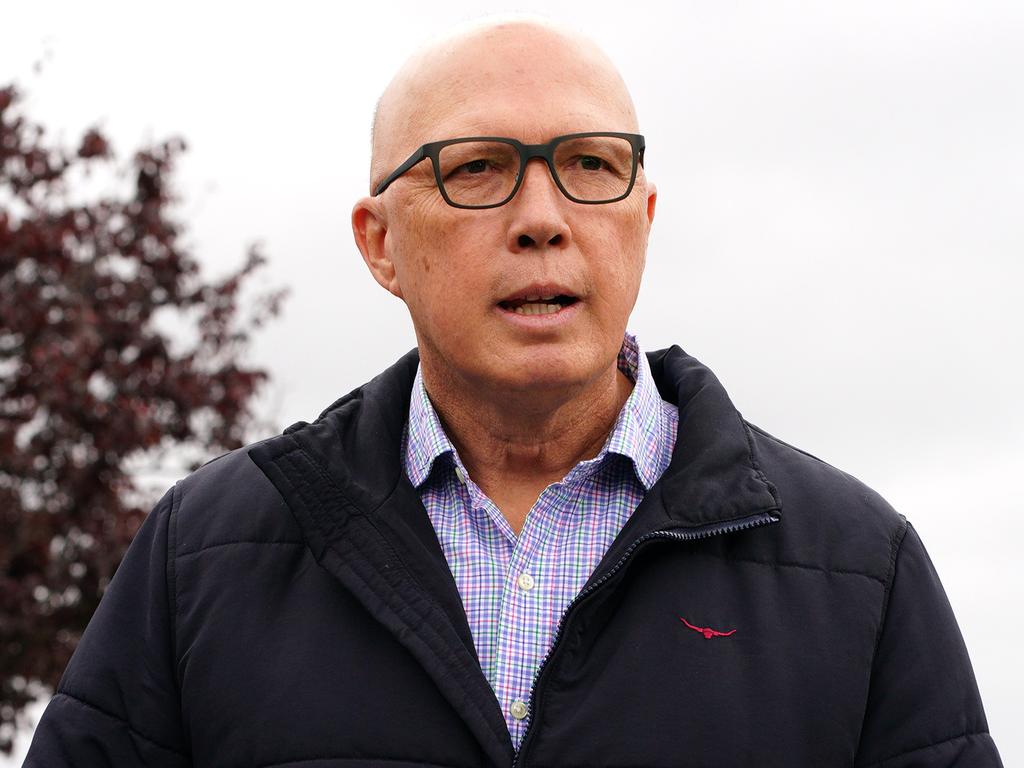

Instead, Peter Dutton says he will actively campaign against the voice without waiting for the parliamentary process to resolve. Constructive engagement and compromise in the best interests of the nation on a topic of great sensitivity and importance have been replaced with a hard no. The party has shown its colours on the constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples in the most dramatic and negative way possible.

It is hard to see what can be salvaged. Dutton says his party still supports constitutional recognition, but he is pushing for regional and local voices to be established by legislation. This confusing position is defined by its rejection of a constitutionally entrenched national voice. It puts the Liberal Party squarely at odds with the strong view of Indigenous peoples as expressed in the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

It is not surprising prominent Indigenous leaders such as Noel Pearson who have worked for years, even decades, with Coalition members feel betrayed.

The loss of bipartisanship is a major blow to the prospects of the referendum. It increases the order of difficulty markedly. No referendum has succeeded without bipartisanship, and of Labor’s 25 attempts to change the Constitution, the only one that succeeded was in 1946 when the proposal won over Robert Menzies’ opposition. On that occasion, Menzies moved an amendment in Parliament to ensure the wording reflected the preferred position of the Liberal Party. Labor accepted this to achieve bipartisanship.

Although things have got much harder, it is wrong to see history as determining the fate of this referendum. As the Aston by-election shows, we live in interesting times in which political orthodoxy can be turned on its head. It is nearly a quarter century since Australia’s last referendum, and popular allegiance to the major political parties has weakened greatly. It is impossible to predict the outcome of a national poll months away in a volatile political climate with a parliamentary process yet to run.

It is also significant that the voice has a strong grassroots base. Referendum after referendum has failed because it has been driven by politicians. The voice is instead embedded in the aspirations of our First Peoples, and has attracted support across the community and civil society. It is the antithesis of Dutton’s description of it as a “Canberra voice”.

The last time a referendum was held on Indigenous issues it was also supported by a large community base. That was the 1967 referendum put to the people by Liberal prime minister Harold Holt. It achieved our greatest-ever referendum success with over 90 per cent voting yes. Such a result is out of reach this time around, but it is still possible for the referendum on the voice to be won.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of law at the University of NSW.

The Liberal Party’s decision to oppose the Indigenous voice to parliament is premature and misguided. It cuts across decades of leadership by the party in Indigenous affairs.