In an interview with The Australian, Macfarlane said the Reserve Bank review “contains an unintended fatal flaw”. He said if the full recommendations of the review were accepted – as the Treasurer initially signalled – the bank’s future would be put “at a huge risk” and the authority of the governor “would be reduced out of all proportion to what any other central bank has done”.

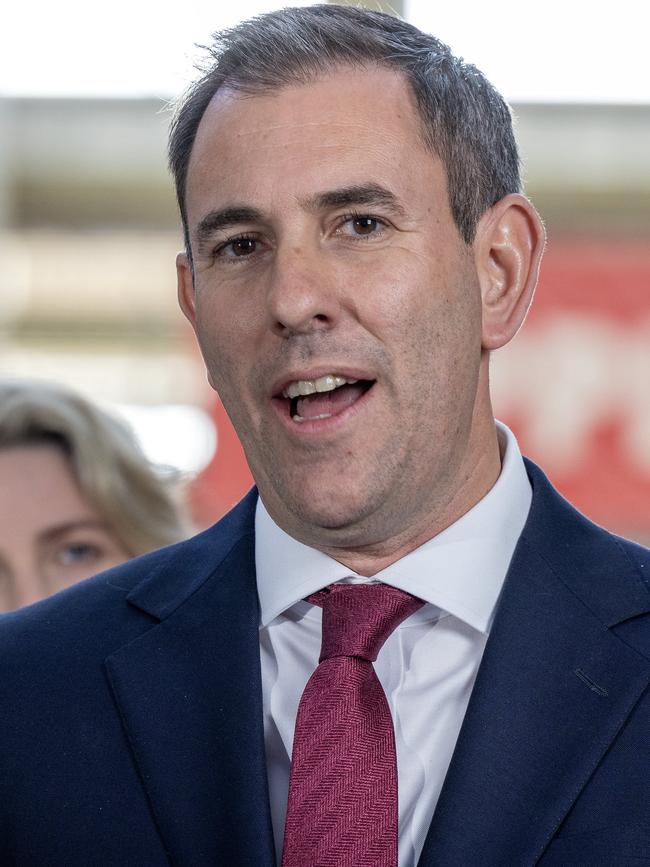

Macfarlane has intensified his critique despite criticism from one of the three authors of the review, Renee Fry-McKibbin, who said in The Conversation that “misinformation is circulating” about the review’s recommendations and disputed Macfarlane’s comments, while Chalmers has said Macfarlane is wrong to claim the proposed changes are radical.

It is apparent, however, that serious doubts are being raised about several of the review’s recommendations.

“I think something is slowly building,” Macfarlane said. “People are realising that this is really a silly review. These issues should have all been sorted three or four months ago. The review should have been put out for public discussion. That it wasn’t is a disgrace.”

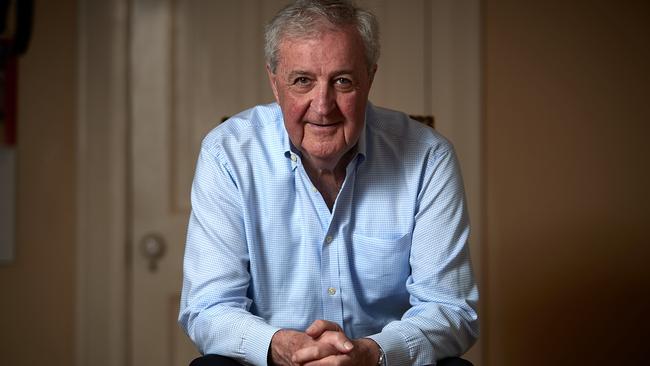

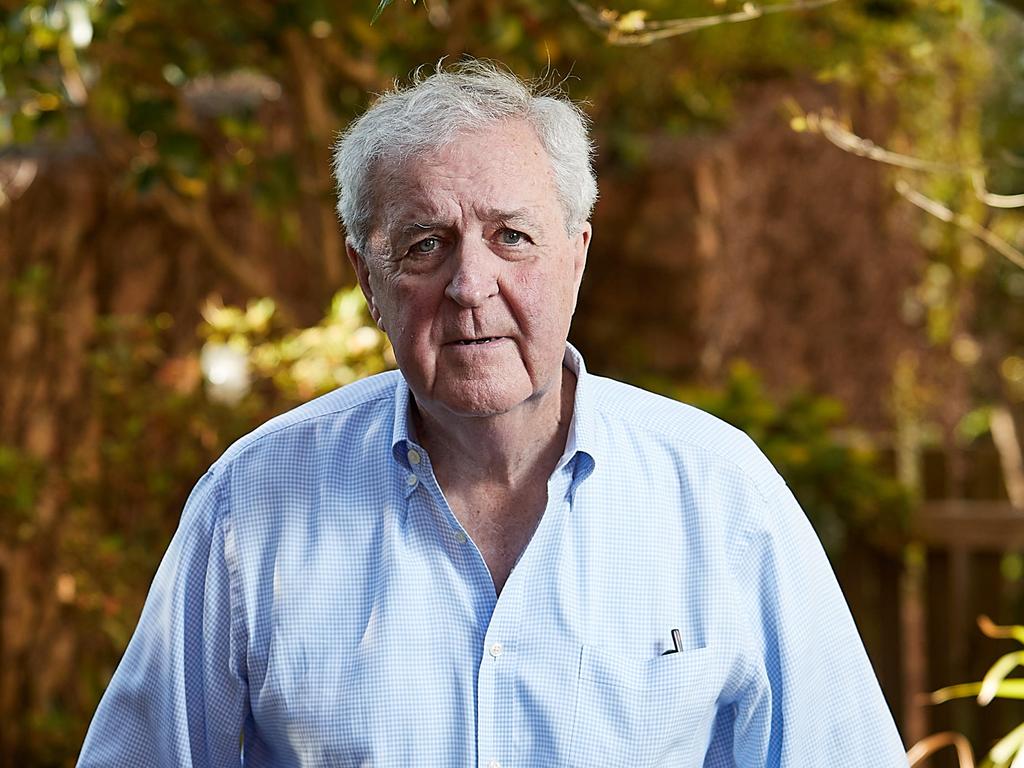

Macfarlane is a critic of the review, its reception and the Treasurer’s decision not to put the review up for debate. Macfarlane served as governor from 1996 to 2006 and was instrumental in entrenching the independence model. He has gone public because he believes there is a serious danger the Reserve Bank will be prejudiced and the report has a vision for the bank that is untenable.

Identifying his precise objection to the review, Macfarlane said: “It retains the existing board, renamed the monetary policy committee, which has a numerical structure suitable for an advisory board which it has always been. But the review changes its purpose into being a decision-making board of experts with published votes.

“These two features are incompatible. They result in a board structure unlike any other central bank. The 290-page report does not recognise this anomaly or attempt to justify it. No other central bank puts the governor in such a weak position.”

Macfarlane says this fusion is the problem. It means the board will have seven out of nine part-time members (including the Treasury secretary) with the governor and deputy governor in a minority of two – while the board is repurposed to become one that is more of a decision-making body. This is what he brands “the fatal unintended flaw”.

The evidence supports Macfarlane’s position. The review summarised its transforming intent: “These recommendations aim to shift the nature of the board from what is in effect an advisory body to one that proactively shapes policy decisions, strategy and the underlying analysis and judgments.”

This is not a modest change. It is a decisive change in purpose and power. If implemented, it raises serious doubts about the governor being locked into a minority position.

Referring to the six part-time board members, Macfarlane said: “You’ve got six people, we don’t know anything about them. The position of governor would be weakened and it would be easy to be overruled. It’s inevitable that this would happen. That’s why no other central bank has considered a structure like this.” It’s why Macfarlane calls the proposal radical and a central bank experiment.

It is an extraordinary critique. Macfarlane is saying the review didn’t comprehend what it was proposing. He said some of the recommendations were naive, many others plain silly. Macfarlane accepts the point there is no change to the current situation of having six part-time members but says to argue that this means the change is modest – the argument made by Chalmers – misses the point because these part-time members are given a new role as decision-makers.

Macfarlane said: “Why do I use the term leap of faith? Because we are being asked to entrust two-thirds of voting power on monetary policy to a group of people we don’t know anything about. They are referred to as experts, but experts in what? The RBA is being asked to outsource its core competence – monetary policy – to a group of unknown competence.”

He asks: how can this work? The report says it wants part-time members to challenge internal RBA thinking. It recommends that votes, but unattributed, be published at the conclusion of each meeting, the practice of some central banks.

Given Australia’s media culture, any divided votes will guarantee media stories along the lines “bank board splits”. And this is supposed to help monetary policy messaging?

The report wants each part-time board member to give an annual speech – sure, so everybody is saying something different. Does that help to clarify monetary policy? “It just shows how naive these people are,” Macfarlane said. He’s right. The review is deluded to think central bank practice from other nations is an easy transfer to Australia. The review’s direction is obvious: it wants at each point to build the internal capacity to challenge bank thinking.

The review reported some experts it consulted wanted to exclude the governor from being chair of the monetary policy committee, a notion it didn’t embrace. It did recommend, however, the creation of a separate governance board on which the governor would sit but with an external member as chair. “That’s just silly,” Macfarlane said. “Like so many thing in this report are silly.”

The notion might be too much for Chalmers. He told the ABC last week, when asked about the governance board, that “we’re working through it”. He added there was a “handful of issues that we haven’t landed yet”. He was working on them with new governor Michele Bullock. Macfarlane said many of them didn’t need legislation. It meant the governor should be able to sort them out. It was a “good sign” that people now recognised not all the recommendations should be implemented.

“I am not arguing for a return to the status quo,” Macfarlane said. “I am arguing that if you want to move to a decision-making board with some part-time members, do the job properly. I would have no case to argue if the review had proposed a model along the lines of the Bank of England, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Bank of Canada or the Bank of Norway. But they have ended up with a model that falls between two stools and in the process greatly weakens the position of the governor.

“I just think they’ve made a mistake. They thought they were doing something moderate. They keep saying, ‘It’s not radical, we didn’t change the structure of the board.’ But that’s precisely the problem. It’s how we got into this mess.”

He raised the issue of accountability. How could the governor discuss monetary policy or be accountable for monetary policy to the public if outvoted at the recent meeting?

Macfarlane also raised a critical issue for the Albanese government. What advice did it get on this review before signing off on such contentious proposals? The Treasury provided much of the secretariat for the review and then presumably advised Chalmers about the conclusion. Convenient. Why no public discussion? It is obvious the media (including the author) failed dismally when the review was released last April by overlooking its litany of flaws.

Have no doubt there has been a cultivated school of opinion – within the government, academe and media – to drive this change in the bank. It won applause from the ACTU and the Australian Council of Social Service, among many other interest groups.

The lesson is also apparent: let’s start paying attention. You mightn’t agree with everything Macfarlane said – but his central proposition is correct and must be addressed.

Five months after Jim Chalmers announced his agreement “in principle” with the far-reaching reforms of the Reserve Bank and won widespread support for the change agenda, the consensus has been shattered by a lethal critique from former governor Ian Macfarlane.