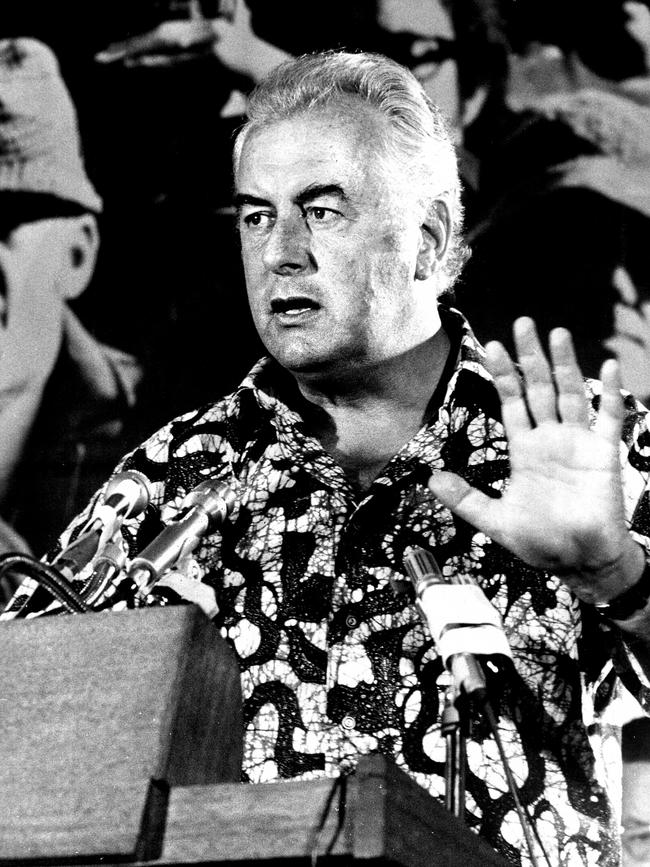

Merely six weeks earlier, Gough Whitlam had promised the president of the Council of the Lithuanian Community in Australia that Labor would make no such move. But in an effort to appease the ALP Left, and eager to flaunt his government’s independence from the United States, he did not hesitate to jettison that commitment as soon as the election was out of the way.

Whitlam’s attempts to justify the reversal, which his own foreign minister, Don Willesee, considered “hasty and politically inept”, can only be described as mendacious. He claimed, for example, that West Germany, Denmark and Switzerland had already recognised the annexation’s legality, despite having explicit advice to the contrary.

He also claimed – again, contrary to advice – that recognition would give Australia greater influence on the Soviet Union and promote the cause of détente. As for the evident tensions between the decision and upholding international law, Whitlam simply brushed them aside.

Repealed by the Fraser government just days after it took office, that decision, and the damage it caused, is now long forgotten. But the ghost of what Clyde Cameron termed a policy “disaster” must be hovering over the Albanese government’s announcement that it is open to recognising Palestinian statehood. Reversing the usual order, while Whitlam’s policy was a farce, this government’s repeat performance has all the makings of a tragedy.

It is, after all, indisputable that international law defines a number of requirements that an entity must meet before it is accorded recognition as a state. And, while the details of the requirements are open to debate, the conclusions James Crawford reached, in the second and final edition of his magnum opus on The Creation of States in International Law, remain compelling.

Crawford, whom the Lowy Institute, when it marked his death in 2021, described as “the most influential Australian international lawyer of all time”, was scarcely an apologist for Israel. On the contrary, he appeared on Palestine’s behalf in the International Court of Justice, of which he was later a distinguished member.

However, he believed it absurd to contend that Palestine met the internationally accepted criteria for recognition as a state “when it self-evidently does not”. The Palestinian Authority, he argued, could not be described as an “exclusively or substantially self-governing power” – it was not, in other words, a sovereign state.

Rather, established under the Oslo (or Interim) Agreements, which strictly limited its competence and left many of the powers that distinguish a sovereign in Israel’s hands, it was merely “an interim local government body”.

That it might be desirable for the situation to be otherwise was “beside the point”. What mattered was that the parties to the Agreements had determined a process by which the allocation of powers could be altered so as to open the road to statehood.

Moreover, they had also entered into “repeated commitments” not to “initiate or take any step”, including Palestinian statehood, “that will change the (legal) status of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip”, before a negotiated agreement had been reached on the outstanding issues. And underscoring the importance of those commitments, the Wye River Memorandum unambiguously stated that any attempted change of status prior to those issues being resolved “would constitute a substantive and fundamental violation of the Interim Agreement”.

As a result, according statehood to the Palestinian Authority would breach international law, both by violating the terms of the Interim Agreements and by flouting the principle – integral to international law since the 19th century and respected in every significant recent case of new state formation – that when the creation of a new state directly impinges on the legal rights of an existing state, international recognition, and notably UN membership, should be conditional on the existing state’s consent.

It would, at the same time, negate the entire legal basis on which the Palestinian Authority rests and so risks being counter-productive, hardening each party’s position while inducing a further descent into unilateralism.

And last but not least, it would set an extremely dangerous precedent. The need for entities to pass an objective test of sovereignty before being recognised as a state has restrained the separatist pressures that – from Aceh and Bougainville to Catalonia – could render an already perilous global context even more volatile.

So too has the longstanding requirement that international recognition only be awarded to a new state after the consent had been secured of states adversely affected: a requirement the international community insisted on in contentious instances ranging from the formation of Bangladesh (1971-74) through to East Timor in 2002 and South Sudan in 2005. As well as being blatantly anti-Semitic, waiving that requirement merely because the Jewish state is involved would open the floodgates with unpredictable consequences.

All that is not to ignore the severity of the current impasse. That the difficulties involved in making any progress are even greater now than when the Oslo Agreements were struck is undeniable. And the fact that a Palestinian state would almost certainly degenerate into a Hamas-dominated Iranian puppet, advancing Iran’s strategy of encircling Israel with a “ring of fire”, adds to the already significant obstacles.

Faced with those difficulties, there is inevitably a temptation – into which the West has fallen time and again – to seek a magic solution that comes drenched in the aura of virtue.

But as Crawford noted, to pretend the Palestinian Authority “already has that for which it is striving (ie, statehood)” not only “misrepresents reality”, it is also reckless. For if a privilege “once conferred cannot be revoked, that is a reason not to confer it, or to do so in as disaggregated a way as possible”.

Compounding the damage by weakening a key pillar of international law – the objective test for statehood, which demands that an entity have, or be on the immediate verge of acquiring, the attributes of sovereignty before being granted UN membership – takes the recklessness to even greater heights.

It is therefore simply impossible to understand how the government reconciles its announcement with its claimed support for Israel’s security and its broader emphasis on a rules-based international order. But this decision has little to do with promoting adherence to international law, and a great deal to do with domestic politics.

On that score at least, Whitlam was prescient. He was, for sure, hopelessly wrong when he claimed that Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania “won’t become separate independent states unless there is a world war which the Soviet Union lost”. And he was at his worst when, extending his intense dislike of the Baltic community to Vietnamese refugees, he cancelled a flight carrying orphans from Saigon to Australia because he wouldn’t allow “f..king Vietnamese Balts” to form “anti-Labor ghettos” in this country.

But he knew what he was talking about when he assured a senior official from the Soviet embassy that the “gradual increase in the size of the Arab population in Australia”, which he welcomed (quite regardless, it seems, of whether or not they formed “ghettos”), would alter domestic politics, undermining support for Israel and strengthening the “progressive” forces. Exactly five decades later, we are paying the price.

On July 3, 1974, shortly after being re-elected, the Whitlam government decided to recognise the legality of the USSR’s annexation of the Baltic republics.