There is, to begin with, the separation between legislative and judicial functions. That separation’s evolution in Britain was relatively slow: as late as the end of the 18th century, nearly a quarter of the statutes passed by the House of Commons involved individual cases that could equally well have been dealt with by the courts.

And the judicial role of the House of Lords was only clearly distinguished from its legislative role in the aftermath of the Appellate Jurisdiction Act of 1876.

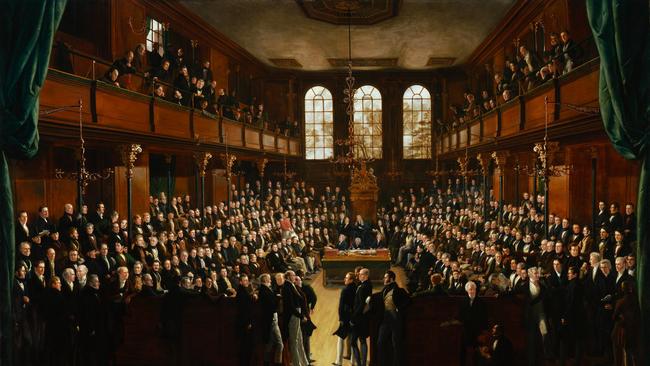

But it is no accident that the Victorian era witnessed the separation’s progressive crystallisation. It was then that the immense powers parliament had acquired in the settlement of 1688 reached maturity; Sir William Blackstone’s famous statement, in his Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), that parliament exercised a “sovereign and uncontrollable authority” that was “despotic”, came fully into its own.

Nothing was more apparent to the period’s great liberal thinkers than the risks that posed to individual liberties. So too was the crucial importance of a sharp delineation between judicial and legislative functions in bringing those risks under control.

John Adams’s Thoughts on Government (1776) proved especially influential. Declaring that “every blessing of society” requires that “the judicial power be distinct from the legislative and the executive, and independent upon both”, Adams’s pamphlet set the intellectual basis for the definition of a distinct “judicial power” in Article III of the American constitution, on which Chapter III of our own Constitution is based.

In England, it acted as a clarion call to successive reformers who, as of the 1830s, sought to differentiate parliament’s responsibility for defining generally applicable laws from the responsibility of the courts, and of the courts alone, for determining their application in particular cases.

The result was not only the increasingly rigorous enforcement of the prohibition on bills of attainder, that is, on parliamentary acts that amounted to a judicial verdict. It was also the development of the sub judice rule, by which legislators were expected to refrain from commenting on individual cases whenever doing so might materially distort the course of justice.

In 1771, it had become legal for parliamentary debates to be recorded; the press’s explosive growth from 1830 to 1870, and the invention in 1837 of modern shorthand (which allowed parliamentary statements to be accurately transcribed and reported verbatim), meant prejudicial comments, made under parliamentary privilege, were immediately echoed nationwide.

Reflecting those trends, the scope of the sub judice rule, which in 1844 applied only to criminal proceedings, was extended over the period to 1893 to civil cases and then to commissions of inquiry that addressed individual behaviour. The rule’s purpose, succinctly expressed in JR Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, was clear: it was (and remains) to ensure parliament undertook its function as “the supreme inquest of the State” without “poisoning the wells of justice before they have begun to flow”.

Reconciling any sensible interpretation of that rule with Gallagher’s behaviour is simply impossible. Far from resiling from prejudicial comment, she engaged in a concerted and co-ordinated strategy to exploit, extend and escalate Brittany Higgins’ allegations.

Her initial target was, of course, the Morrison government; to that end, she sought to convert the allegations into a political trial, as Otto Kirchheimer classically defined it in Political Justice (1961): that is, a trial which, while “riding roughshod over the defendant’s rights, squeezes propaganda value from distortions of actual events, in an effort to bring disrepute upon a political foe”.

But this was not simply a political trial; it was to be a show trial. That term can be used advisedly, for it is the essence of a show trial that instead of allowing the normal investigative and adjudicative processes to run their course, it seeks to stage a Manichean morality play pitting good against evil, with the defendant – regardless of individual guilt or innocence – serving as the scapegoat for the vice being demonised: in this instance, the alleged sins #MeToo was assailing.

Harnessing the power and prestige of the state to erase the presumption of innocence and tilt the balance against the defendant, show trials are rituals of vengeance, staged not for the benefit of justice but to fuel the bloodlust of the mob.

It is hard to think of anything more starkly at odds with Hannah Arendt’s precept that the foundation of the rule of law is “the principle of personal culpability: the requirement that no defendant be held responsible for the wrongs of others”.

But Gallagher’s disregard for the norms of parliamentary democracy didn’t stop there. There is every reason to believe she misled parliament, which has been regarded as a serious offence since at least 1806, when the principle of ministerial accountability was cemented. And although the episode remains shrouded by the secrecy in which the government has enveloped it, she seems to have been implicated in an ex gratia payment to Higgins.

There too, the Westminster conventions are unambiguous. Such payments can, in narrow circumstances, be legitimate; but it has long been accepted that favours dispensed for political services rendered raise serious concerns.

Too little is known about the payment to Higgins to assess its legitimacy; for precisely that reason, the principle of publicity, which since Edmund Burke’s great campaign for the Economical Reform Act of 1795, requires that the government, when pressed, comprehensively account for any such payments, should have come fully into play. But despite her responsibility as Finance Minister for propriety in the use of public funds, Gallagher has adamantly refused to provide the transparency taxpayers can expect and demand.

And as if all that were not bad enough, Gallagher has now compounded her errors by branding Bruce Lehrmann a rapist, just as defamation proceedings centred on that charge are under way, as is an official inquiry into the decision to press charges. Perhaps that will work for her: after all, she played a vital role in creating the atmosphere in which there was intense political pressure for Lehrmann to be prosecuted – and her conduct was rewarded by high ministerial office.

But Kirchheimer’s warning, informed by his decades of experience, should echo in her ears. “Justice in political matters,” he wrote, “is the most ephemeral of all divisions of justice; a turn of history may undo its work.” As history turns, Katy Gallagher’s strategy is turning to dust – and her reputation with it.

Although the Coalition’s censure bid failed, the difficulty with Katy Gallagher lies in identifying a fundamental principle of the Westminster system she has not breached. It may be that she is competent; but that hardly excuses conduct that flouts the basic norms on which parliamentary democracy rests.